Photographs: Simone de Greef

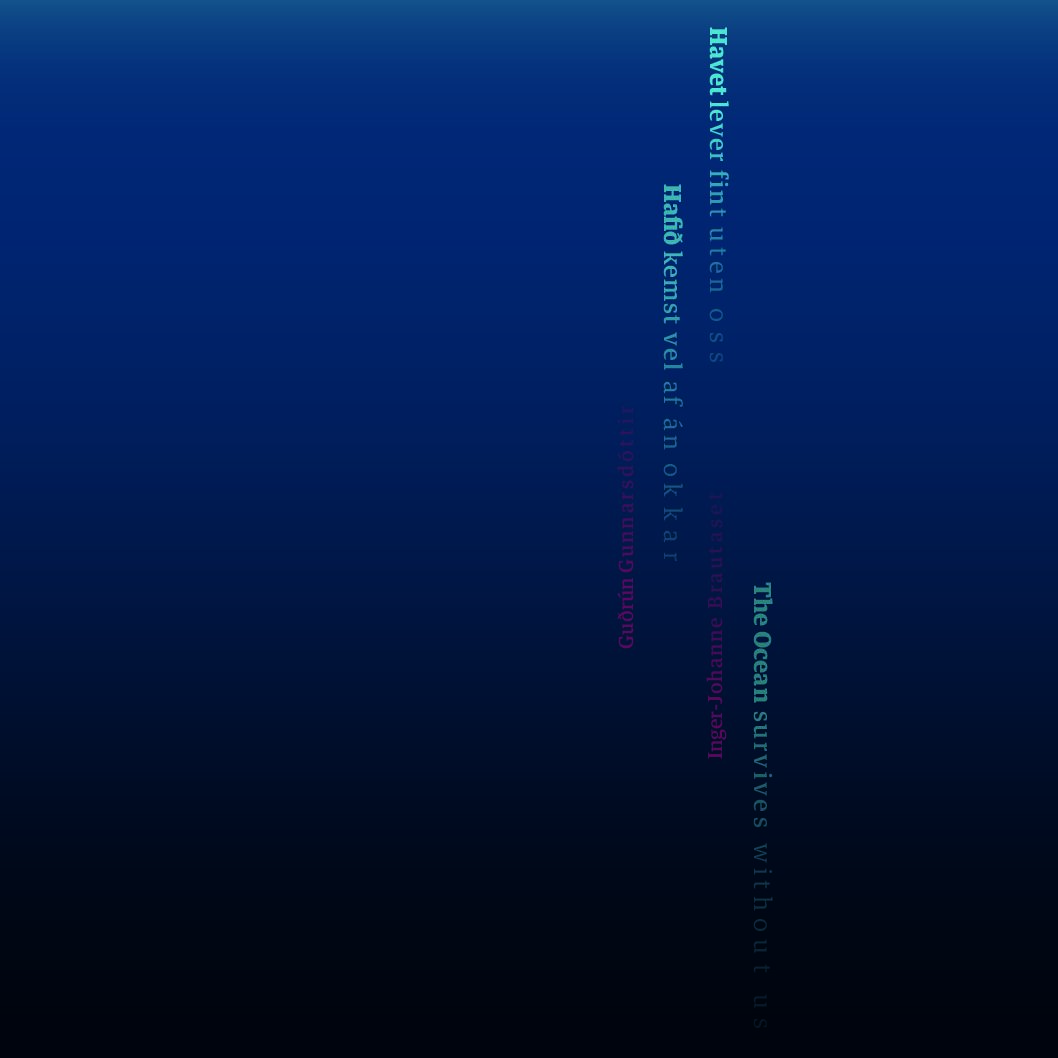

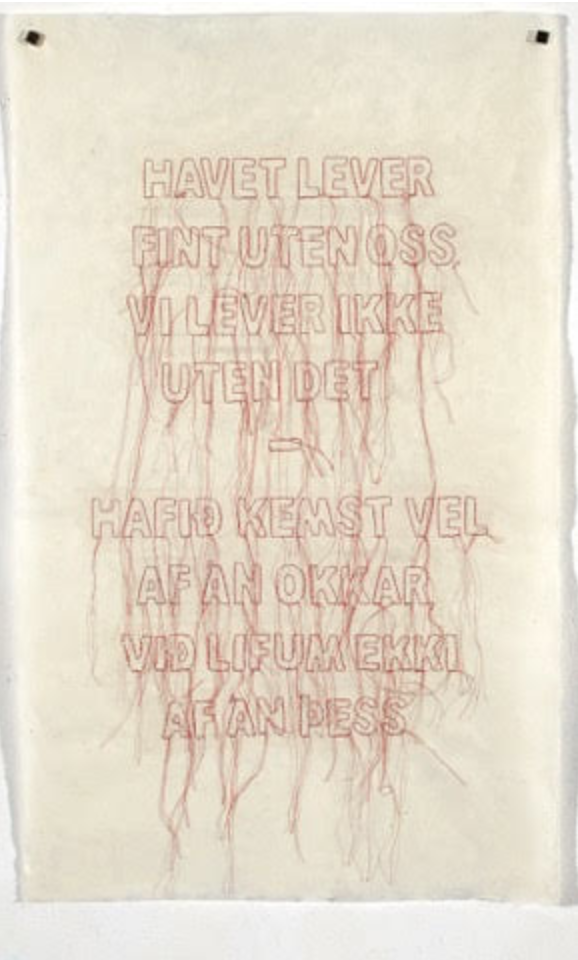

The ocean survives without us.

Guðrún Gunnarsdóttir og Inger-Johanne Brautaset

July 3rd – December 22nd 2021

“The Ocean survives without us” is a collaborative project about the ocean between Iceland and Norway where we wish to dive into an unknown, unexplored underworld – we swim between sharks, plants, plankton and unknown species, and now, in addition, also plastics, a new breed.

The book “Shark Drunk” by Morten Strøksnes has been a common reading for this exhibition.

When fish drown

Morten Strøksnes

When we talk about global warming, we are most concerned with how our lives on dry land are affected. This is not surprising, because it is a very long time since our predecessors crawled ashore and developed lungs and bones instead of gills and fins. At the same time, this focus is a bit skewed. Because even though the state of the earth is obviously affected by what happens on land, not least by what we do, the sea is more crucial. The ocean is the great climate regulator on our planet.

In recent millennia, living conditions in the sea have been surprisingly stable. This is no longer the case. The reason is our greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, the ocean has absorbed most (93 percent) of the extra heat our emissions have caused. Not only the heat but also huge amounts of CO2 have been stored in the world’s oceans. Had this not been the case, the earth would already have been many degrees warmer.

Unfortunately, this blessed mechanism has its limit and a price. The bill is on the table and we can haul out the time. But we’ve got nowhere to run.

The warming of the ocean is not necessarily a disaster in itself, although it does change ecosystems dramatically (and they have always changed). What poses the big problems in the long run is that warmer oceans store less carbon, so that global warming is gaining speed. Warm seas also contain less oxygen than cold seas.

Worse, increasing levels of CO2 make the ocean increasingly acidic. After we started emitting large amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere only two hundred years ago, the pH value in the ocean has fallen slowly but surely. Already by the end of this century, it will probably have dropped to pH 7.8 (from 8,2 two hundred years ago), science tells us. If so, the sea will be more acidic than most fish and other marine species can tolerate. The changes happen too fast for the species to adapt. Ecosystems will die, from the top of the food chains and down to tiny algae (phytoplankton).

By the way, did you know that a species of these microscopic algae «invented» photosynthesis deep back in earth’s prehistory? By using the energy from the sun, it managed to bind CO2. The waste product of this process was gas called oxygen. This is how it started for us: blue-green algae/ bacteria in the ocean caused the level of CO2 in the atmosphere to drop, and the oxygen level to rise. In the end it was possible to breathe. These same blue-green algae, which science only a few decades ago did not know about, have produced about two-thirds of the oxygen found on earth.

«It´s probably gonna be all right», we have a natural propensity to assume, maybe as a deeply embedded survival mechanism. But often it does not go well, especially if we try to see things in the long run (something we are very bad at). For instance: At the end of the Permian (299–251 million years ago), the earth experienced the worst mass extinction in the planet’s history. Volcanic eruptions in Siberia added enormous amounts of phosphorus to the atmosphere, and most of it ended up in the ocean. Algae love phosphorus, and the algae bloom went crazy. This drained the ocean of oxygen. When all the biological material died and rotted, the ocean was filled with sulphur gases. The disaster wiped out most (96 per cent) of the species in the ocean, and these are now only known as fossils, if at all.

All mass extinctions have been linked to changes in the ocean, directly or indirectly, maybe initiated by spectacular events such as extreme volcanic eruptions or meteor showers. But the real disasters were due to more insidious and slow-moving processes Hollywood will never make any movies out of. To changes in ocean temperature, acidity, oxygen saturation and levels of CO2 or phosphorus.

What we do know is that the temperature is rising faster today than during the largest mass extinction the earth has ever seen. Science tells us that the oxygen level in the ocean drops due to our “fertilization”, and because warmer oceans bind less oxygen than colder ones. Am I suggesting that we are in a new mass extinction? No, there are hundreds of leading scientists who do that.

Things rarely happen in exactly the same way. But laws of nature, not whims or fancies, govern chemical reactions. When the chemistry in the atmosphere and in the ocean changes, this will have major, predictable consequences for life on earth as we know it. The life forms that are adapted to today’s climate and chemical balance are built for exactly these conditions, and not suitable for survival when dramatic changes occur.

Science gives little reason for optimism. Even if our emissions stopped completely and momentarily (as is well known, they actually go up), it would not freeze the ongoing processes caused by man-made global warming. The cycles and exchange of carbon between air, sea and earth would continue. If there was suddenly far less CO2 in the atmosphere, the ocean would start to emit large amounts of CO2 to adapt to the new situation. Due to such feedback mechanisms, the effect of our emissions will work in the foreseeable future.

Geologists, glaciologists and climate scientists have taught us an enormous amount about the earth’s past. We know that there has been extremely much more CO2 on earth in the past. A lot warmer. Also much colder. Or that the sea used to be 30 meters higher than now. But this is not reassuring. For also back then the earth would not be liveable for us. Dramatic climate change has on a number of occasions created mass extinctions that wiped out almost everything and everyone, except the hardiest creatures. Unfortunately, there is little indication that we, even with our extremely advanced technology, belong to this exclusive group.

Unlike most living creatures on earth, we cannot live in the ocean. But we cannot live without it either.