ENN OG AFTUR – SCHON WIEDER – ONCE AGAIN

Hlynur Hallsson

Salur 4

7. febrúar – 23. ágúst 2026

Andstaða Hegels gegn formálum endurspeglar eftirfarandi byggingu: formáli/texti – óhlutbundin regla/sjálfhreyfandi virkni. Samþykki hans á formálum endurspeglar aðra byggingu: formáli/texti = táknberi/táknmerking. Og heiti „–“ í þessari jöfnu er hið hegelska Aufhebung.

– Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, „Translator’s Preface“ í Of Grammatology

Innan marka möguleika sinna, eða hins sýnilega möguleika, snýst þýðing um muninn á táknmerkingu og táknbera. En þar sem þessi munur er aldrei hreinn, er þýðing það enn síður, og hugtakinu umbreyting verður að skipta út fyrir hugtakið þýðing: stýrða umbreytingu eins tungumáls af öðru, eins texta af öðrum. Við höfum aldrei þurft og munum aldrei þurfa að fást við einhvers konar „flutning“ hreinna táknmerkinga sem táknkerfið – eða „farartækið“ – myndi skilja eftir ósnortnar og óspilltar, frá einu tungumáli til annars, eða innan sama tungumáls. (Pos 31)

– Jacques Derrida, Positions

Hið óhugsandi er ekki, eins og auðvelt er að sýna fram á, formgerð án miðju (því að við sjáum sífellt að slíkur skortur er einkennandi fyrir formgerð; þetta er það sem Derrida sýnir); hið óhugsandi er fremur formgerð eða heild óháð allri spennu milli sjálfrar sín og einhvers fjarverandi uppruna. Hið óhugsandi er tónn.

– Fred Moten, In the Break

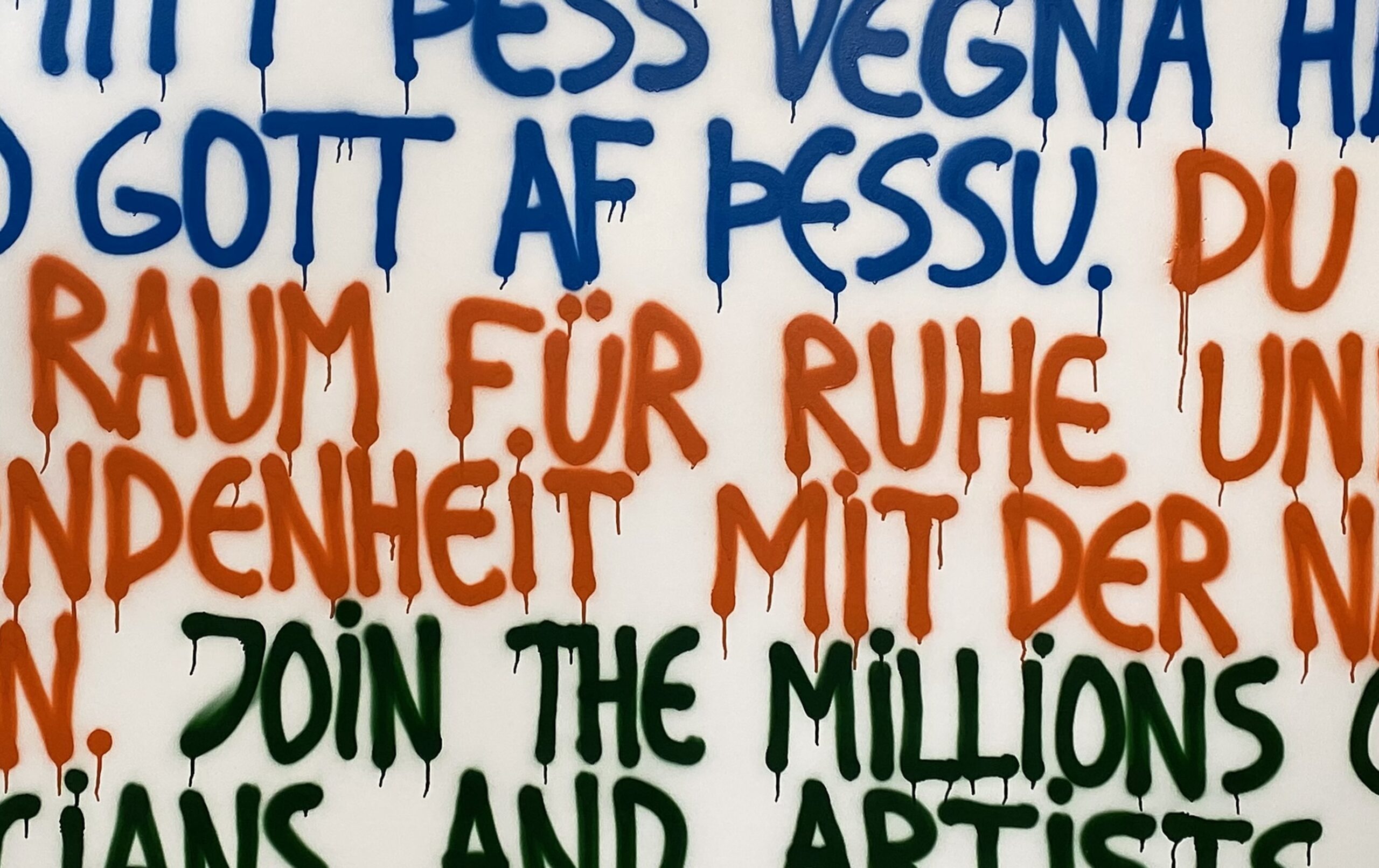

Hlynur Hallsson er íslenskur listamaður sem vinnur með texta. Textinn birtist spreyjaður í almannarýminu (borgarumhverfi) og spreyjaður eða uppsettur í hálfopinberu rými (sýningarsölum, galleríum, söfnum eða listamannabústöðum). Textaverkin eru samin undir áhrifum af leyfum og skyldum sem spretta af þeim samfélagssáttmálum sem listamaðurinn er hluti af. Textar Hallssonar eru handskrifaðir, eða réttara sagt handspreyjaðir, á fleiri en einu tungumáli, oftast á íslensku, þýsku og ensku. Merking orðanna í einu tungumáli, einangruðu frá hinum, er ekki bein þýðing þeirra orða sem fylgja á hinum tungumálunum; fremur má líta á þau sem sundurleit sjónarmið, hliðar á umdeildu efni eða staðsetningarmerki fyrir upphafspunkt sem gjarnan er ósagður eða einungis gefinn í skyn með orðunum sjálfum. Þegar tungumálin eru lesin saman verður merking þeirra oft bæði flóknari og sterkari; minnir mögulega á uppsöfnuð áhrif þess að sjá allar frásagnir Rashomon áður en dregin er ályktun um hvernig maður lést.

Textasamklipp – orð fengin af veraldarvefnum, allsráðandi uppsprettu upplýsinga og rangupplýsinga – er verkfæri sem Hlynur beitir oft. Textasamklipp er einnig lykilaðferð í stofnanarýni í hinum þekkta gjörningsfyrirlestri bandaríska listamannsins og myndlistarkennarans Andreu Fraser (f. 1965), Official Welcome (2001). Í þeim fyrirlestri nýtti Fraser sér ræður fluttar við hátíðleg tækifæri í listheiminum, og í sífellt æsilegri lofræðunni varð framsetning hennar æ sundurslitnari og stjórnlausari, uns hún afklæddist fyrir framan áhorfendur og varð að „hlutgerðu“ stöðluðu lifandi listaverki. Fraser raðar saman orðræðum þekktra opinberra persóna og afmáir uppruna þeirra, á sama tíma og hún skapar algjörlega nýtt samhengi þar sem orðaröð, brot úr málsgreinum, setningar og merkingarlausar tengingar heyrist og er túlkuð. Þetta verk frá því snemma á ferli Fraser á sér hliðstæður í sumum dadaískum samklippsaðferðum sem Hlynur beitir: að svipta opinber orð þekktra persóna tengslum sínum við upprunalegt samhengi og stilla orðunum upp í rými til að framkalla á köflum grínkennd, umhugsunarverð eða truflandi áhrif. Textarnir, eða réttara sagt orðin, eru staðbundin og valin af Hlyni í ljósi málefna sem eru ofarlega í opinberri umræðu á þeim stöðum þar sem hann sýnir.

Í upphafi 21. aldar, á meðan Hlynur dvaldi í listamannabústað í Marfa í Texas, vitnaði hann í ummæli um þáverandi forseta Bandaríkjanna, George W. Bush, og Osama bin Laden, á sama tíma og „stríðið gegn hryðjuverkum“ var að hefjast. Spreyjaður textinn sást frá götunni út um verslunarglugga og sýningarrýmið var upplýst á kvöldin. Sumir íbúar Texas urðu móðgaðir yfir ummælunum þar sem verkið var gagnrýni á forseta „þeirra“, sem hafði verið ríkisstjóri Texas fyrir kosningarnar árið 2000. Kvartanir almennings leiddu í kjölfarið til þrýstings á sýningarrýmið. Hlynur ákvað þá að endurgera verkið sem gjörning á mörkum hegelskrar Aufhebung, sem er alger afneitun hugtaks til að byggja nýtt, og relève Derrida, sem felur í sér afturhvarf til upprunalegs hugtaks án þess að eyða því með öllu, sem leiðir til blæbrigðamunar: að skapa nýja fullyrðingu því að ógilda á gegnsæjan hátt fyrri fullyrðingar eða hugtak.

Á síðari árum, meðal annars á Oslóartvíæringnum, hefur Hlynur víkkað út svið sitt með því að bæta við tungumálum sem hann vinnur með. Í því metnaðarfulla verkefni var markmiðið að ná betur til, endurspegla og eiga samtal við nýja minnihlutahópa í Noregi, og að skapa eins konar skrá yfir jaðartungumál sem eru töluð og skilin í Osló samtímans. Þetta fól einnig í sér að nota frumbyggjatungumál Samanna. Textaverk Hlyns birtust í norrænni höfuðborg sem er að ganga í gegnum lýðfræðilega umbreytingu, og verkin voru sérstaklega mótuð til að bregðast við þeirri breytingu. Útkoman var verkefni á sjö stöðum víðs vegar um borgina þar sem pólska og litháíska fengu rými, samhliða norsku, ensku og íslensku. Dari, tungumál meðal afgansks fólks, og sómalíska bættust einnig við og vitna um aukið alþjóðlegt aðdráttarafl borgar á borð við Osló. Samíska, tungumál frumbyggja norðursins – fólks sem sögulega hefur verið svipt réttindum, flutt nauðugt á brott og neytt til menningarlegrar aðlögunar að ríkjandi hugmyndum um norska sjálfsmynd – tók sér rými í almannarými höfuðborgarinnar. Þessi verkaröð markaði þáttaskil fyrir listamanninn, þar sem hann notaði nú letur og orð í tungumálum sem hann talar ekki sjálfur. Með því snúa bókstafirnir sjálfir aftur í hlutverk áþreifanlegra grafískra hönnunarforma sem listamaðurinn getur prófað og vegið og metið í opinberu rými.

Fyrir þessa sýningu hefur Hlynur skapað tvö ný textaverk, bæði á þremur tungumálum: hið fyrra greinir á milli þeirra með litunum bláum (íslenska), rauðum (þýska) og grænum (enska) og snýst um skilgreiningu á þjóðarmorði; hið síðara er með gullnum bókstöfum án aðgreiningar tungumálanna þriggja og fjallar um svokallað „svart gull“, olíu og kapítalíska hagsmuni sem styðja framleiðslu hennar. Auk þessara spreyjuðu veggverka sýnir listamaðurinn ljósmyndaverk frá ferðum sínum um Evrópu, með texta á íslensku, þýsku og ensku. Myndatextarnir miðla sömu merkingu á hverju tungumáli og vísa til myndarinnar með staðreyndum og á lýsandi hátt. Þeir eru þó persónulegir og ekki fullgildir lýsingartextar í þeim skilningi sem notaður er á vefnum fyrir sjónskerta. Hlynur leikur sér þannig að bilinu milli merkingar sem dregin er af ljósmynd og tungumálsins sem rammar hana inn.

Þegar Hlynur var spurður hvaða þrjú „ó-listrænu“ orð gætu lýst starfi hans, svaraði hann: „communication, samskipti, bewirkung.“ Þetta er lýsandi. Orðin undirstrika kjarna starfshátta hans: að skapa andrík verk sem hafa ólík áhrif á fólk sem talar mismunandi tungumál, hins vegar verk sem koma á samskiptum, ekki í merkingu fjárhagslegra viðskipta heldur í lifandi félagslegu rými, og að breyta þáttum eða virkja þá, að koma einhverju til leiðar.

Sú aðferð Hlyns Hallssonar að velja þríeyki tungumála veitti mér einnig innblástur til að velja þann hóp hugsuða sem vitnað er í í upphafi þessa texta: Hegel, Derrida í gegnum Spivak, og Derrida í gegnum Moten. Að mínu mati falla starfshættir Hlyns almennt undir það sem Moten kallar „ensemble“: að hugsa með og í gegnum aðra hugsuði. Hegel og Derrida kynna díalektík, aðferð sem síðan fellur inn í sjálfa sig, hrynur og mótar hugsun Motens – og margra annarra. Aufhebung, différance, ensemble eru þau hugtök sem, að mínu mati, stuðla að skilningi á Enn og aftur – schon wieder – yet once again, sýningu sem mun hliðra til merkingu og boðskap í huga áhorfenda og reyna á, jafnframt því að eiga samtal við, sameiginlega reynslu þeirra af samtímalist og hversdagsmáli.

Text by Dr. Craniv Boyd.

1) Formáli þýðanda í: Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, þýðing eftir Gayatry Chakravorty Spivak (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1997), bls. 10. (Áhersla mín.)

2) Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, þýðing eftir Gayatry Chakravorty Spivak (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1997), bls. 73. (Áhersla mín.)

3) Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), bls. 57. (Áhersla mín.)

4) Þetta eru þau tungumál sem listamaðurinn talar reiprennandi.

5) Sjá kvikmynd japanska leikstjórans Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998), Rashomon (1950), þar sem morði er “lýst” frá sjónarhorni ólíkra þátttakenda og vitna að glæpnum.

6) Fraser sýndi gjörning sinn first í einkasamkvæmi MICA-stofnunarinnar árið 2001. Sjá Baring the Truth eftir Barböru Pollack, Art in America, júlí 2002, á netinu: https://web.archive.org/web/20050421131255/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1248/is_7_90/ai_88582353.

7) Hlynur tók þátt í fyrsta Oslóartvíæringnum í Noregi árið 2019. Það var fyrsta og síðasta útgáfa tíværings sem átti að standa í fimm ár, frá 2019 til 2024. Oslóartvíæringurinn hlaut svipuð örlög og Jóhannesarborgartvíæringurinn í Suður-Afríku, honum lauk þremur árum áður en til stóð og hefur ekki verið endurvakinn. Hlynur og skipuleggjendur tvíæringsins fengu sjö höfunda – Markús Þór Andrésson, Æsu Sigurjónsdóttur, Alexander Steig, Einar Bjarka Malmquist, Jill Maurah Leciejewski, Kristínu Kjartansdóttur og Kari Ósk Grétudóttur Ege – til að skrifa ritgerðir u hvert þeirra verka sem hann vann í borgarlandslagið. Ritgerðirnar má finna hér: https://www.oslobiennalen.no(participant/hlynur-hallson/.

8) Varðandi skilning á tungumálum og endurgerð ritaðra tákna detta mér í hug margar svartar suður-afrískar listakonur í bæjum á landsbyggðinni sem ég tók viðtöl við fyrir nýjustu bók mína. Þar var sjaldgæft að konur af eldri kynslóðum kynnu að lesa og skrifa en samt sýndu þær oft hæfni til að skrifa nafnið sit tog leika sér með hönnunarform latínuletursins í listrænni hönnun sinni. Sjá Craniv Boyd, Assemblages of Belonging: Murals Beadwork and Ndebele Identity in South Africa (Bielefeld: handrit 2025).

Hlynur Hallsson (1968) stundaði myndlistarnám á Akureyri og í Reykjavík og framhaldsnám í myndlist í Hannover, Hamborg og Düsseldorf. Hann hefur tekið þátt í um 120 samsýningum og sýnt verk sín á yfir 70 einkasýningum meðal annars í Listasafni Reykjavíkur, Nýlistasafninu, Listasafninu á Akureyri, hjá Kuckei+Kuckei í Berlín, Kunstraum München, hjá Chinati Foundation í Texas og hjá Overgaden í Kaupmannahöfn. Hann var safnstjóri Listasafnsins á Akureyri 2014-2024 og hefur einnig unnið sjálfstætt sem sýningastjóri. Hlynur hefur kennt myndlist við Listaháskólann og Myndlistaskólann á Akureyri. Hann hefur einnig gefið út nokkrar bækur og bókverk.Verk Hlyns snúast gjarnan um samskipti, tengingar, texta, tungumál, landamæri, stjórnmál, hversdagslega hluti og hvað við lesum úr aðstæðum. Hann vinnur gjarnan með texta, teikningar, ljósmyndir, gjörninga, hluti, vídeó og innsetningar.