Only data

Jeannette Castioni

Foyer

7th of February – 23rd of August 2026

“Art is a game between all people of all periods.”

Marcel Duchamp1

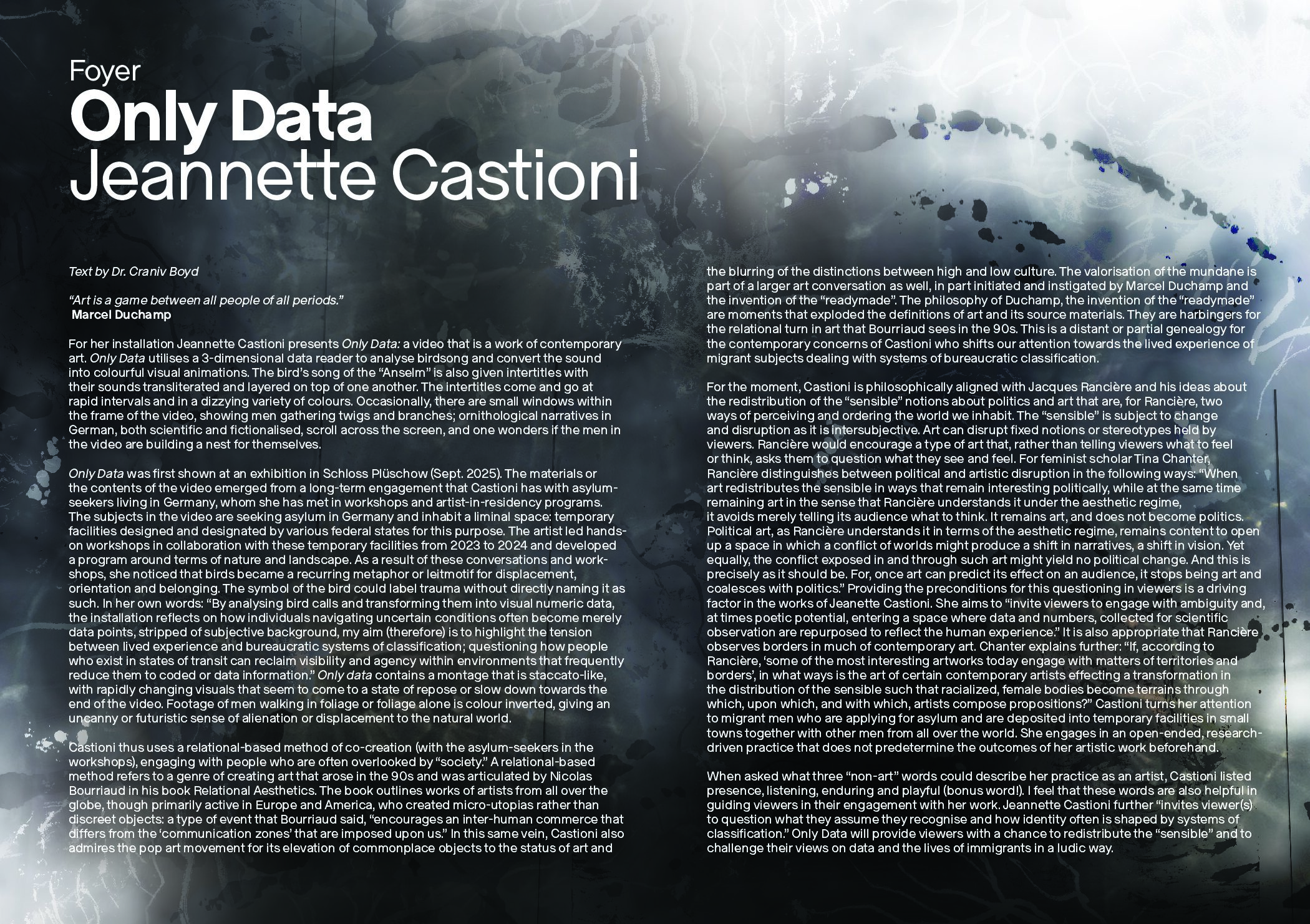

For her installation at Listasafn Árnesinga, Jeannette Castioni presents Only Data: a video that is a work of contemporary art. Only Data utilises a 3-dimensional data reader to analyse birdsong and convert the sound into colourful visual animations. The bird’s song of the “Anselm” is also given intertitles with their sounds transliterated and layered on top of one another. The intertitles come and go at rapid intervals and in a dizzying variety of colours. Occasionally, there are small windows within the frame of the video, showing men gathering twigs and branches; ornithological narratives in German, both scientific and fictionalised, scroll across the screen, and one wonders if the men in the video are building a nest for themselves.

Only Data was first shown at an exhibition in Schloss Plüschow (Sept. 2025).2 The materials or the contents of the video emerged from a long-term engagement that Castioni has with asylum-seekers living in Germany, whom she has met in workshops and artist-in-residency programs. The subjects in the video are seeking asylum in Germany and inhabit a liminal space: temporary facilities designed and designated by various federal states for this purpose. The artist led hands-on workshops in collaboration with these temporary facilities from 2023 to 2024 and developed a program around terms of nature and landscape. As a result of these conversations and workshops, she noticed that birds became a recurring metaphor or leitmotif for displacement, orientation and belonging. The symbol of the bird could label trauma without directly naming it as such. In her own words: “By analysing bird calls and transforming them into visual numeric data, the installation reflects on how individuals navigating uncertain conditions often become merely data points, stripped of subjective background, my aim is to highlight the tension between lived experience and bureaucratic systems of classification, questioning how people who exist in states of transit can reclaim visibility and agency within environments that frequently reduce them to coded or data information.”3 Only data contains a montage that is staccato-like, with rapidly changing visuals that seem to come to a state of repose or slow down towards the end of the video. Footage of men walking in foliage or foliage alone is colour inverted, giving an uncanny or futuristic sense of alienation or displacement to the natural world.4

Castioni thus uses a relational-based method of co-creation (with the asylum-seekers in the workshops), engaging with people who are often overlooked by “society.” A relational-based method refers to a genre of creating art that arose in the 90s and was articulated by Nicolas Bourriaud in his book Relational Aesthetics. The book outlines works of artists from all over the globe,5 though primarily active in Europe and America, who created micro-utopias rather than discreet objects: a type of event that Bourriaud said, “encourages an inter-human commerce that differs from the ‘communication zones’ that are imposed upon us.”6 In this same vein, Castioni also admires the pop art movement for its elevation of commonplace objects to the status of art and the blurring of the distinctions between high and low culture. The valorisation of the mundane is part of a larger art conversation as well, in part initiated and instigated by Marcel Duchamp and the invention of the “readymade”. The philosophy of Duchamp, the invention of the “readymade”7 are moments that exploded the definitions of art and its source materials. They are harbingers for the relational turn in art that Bourriaud sees in the 90s. This is a distant or partial genealogy for the contemporary concerns of Castioni who shifts our attention towards the lived experience of migrant subjects dealing with systems of bureaucratic classification.

For the moment, Castioni is philosophically aligned with Jacques Rancière and his ideas about the redistribution of the “sensible” notions about politics and art that are, for Rancière, two ways of perceiving and ordering the world we inhabit. The “sensible” is subject to change and disruption as it is intersubjective. Art can disrupt fixed notions or stereotypes held by viewers. Rancière would encourage a type of art that, rather than telling viewers what to feel or think, asks them to question what they see and feel. For feminist scholar Tina Chanter, Rancière distinguishes between political and artistic disruption in the following ways: “When art redistributes the sensible in ways that remain interesting politically, while at the same time remaining art in the sense that Rancière understands it under the aesthetic regime, it avoids merely telling its audience what to think. It remains art, and does not become politics. Political art, as Rancière understands it in terms of the aesthetic regime, remains content to open up a space in which a conflict of worlds might produce a shift in narratives, a shift in vision. Yet equally, the conflict exposed in and through such art might yield no political change. And this is precisely as it should be. For, once art can predict its effect on an audience, it stops being art and coalesces with politics.”8 Providing the preconditions for this questioning in viewers is a driving factor in the works of Jeanette Castioni. She aims to “invite viewers to engage with ambiguity and, at times poetic potential, entering a space where data and numbers, collected for scientific observation are repurposed to reflect the human experience.”9 It is also appropriate that Rancière observes borders in much of contemporary art. Chanter explains further: “If, according to Rancière, ‘some of the most interesting artworks today engage with matters of territories and borders’, in what ways is the art of certain contemporary artists effecting a transformation in the distribution of the sensible such that racialized, female bodies become terrains through which, upon which, and with which, artists compose propositions?”10 Castioni turns her attention to migrant men who are applying for asylum and are deposited into temporary facilities in small towns together with other men from all over the world. She engages in an open-ended, research-driven practice that does not predetermine the outcomes of her artistic work beforehand.

When asked what three “non-art” words could describe her practice as an artist, Castioni listed presence, listening, enduring and playful (bonus word!). I feel that these words are also helpful in guiding viewers in their engagement with her work. Jeannette Castioni further “invites viewer(s) to question what they assume they recognise and how identity often is shaped by systems of classification.” 11 Only Data will provide viewers with a chance to redistribute the “sensible” and to challenge their views on data and the lives of immigrants in a ludic way.

Text by Dr. Craniv Boyd.

1) As quoted in Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon: Les Presses du reel, 2002), p. 19.

2) The artist was in residency at the Schloss Plüschow Artist Residency program in Mecklenburg Vörpommern in September 2025. See the Facebook page of the artist residency: https://www.facebook.com/plueschow/.

3) Email correspondence with the artist, 7 December 2025.

4) Another Icelandic artist utilizes color inversion with botanical photography to imagine a botanical future. See the recent publication of Katrin Elvarsdóttir, A Botanical Future, at https://www.bergcontemporary.is/en/artists/katrin-elvarsdottir.

5) The most acclaimed of the artists championed by Bourriaud is Rirkrit Tiravanija, who cooked for collectors and at exhibition openings and who was a radical exemplar of the “social interstice.” Tiravanija is perhaps the artist most closely associated with the term “relational aesthetics.” See Bourriaud (2002). However, there are several other artists who also use relationships with informants to generate or co-create works of art that speak to social realities of the subjects: Annika Erikson, Staff of the Moderna Museet (2000) —see the artist’s portfolio at https://annikaeriksson.com/work/staff-at-sao-paulo/—and Elin Wickström in her work Cool or Lame (2003). See Billy Ehn, “Between Contemporary Art and Cultural Analysis: Alternative Methods for Knowledge Production”, InFormation: Nordic Journal for Art and Research, vol. 1, no.1 (2012), pp.4-18

6) Bourriaud (2002), p.16.

7) The readymade as an art object opens up more aspects of the world with the potential to become art. For the philospher Boris Groys, the readymade also has a philosophical corollary in Antiphilosophy. See Boris Groys, Introduction to Antiphilosophy (London: Verso, 2012).

8) Tina Chanter, Art, Politics and Rancière: Broken Perceptions (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), pp 44-45

9) Email correspondence with the artist, 7 December 2025.

10) Tina Chanter, Art, Politics and Rancière: Broken Perceptions (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), p. 50.

11) Email correspondence with the artist, 7 December 2025.

Jeanette Castioni wants to thank the art residency Schloss Plüschow in Mecklenburg Vorpommern north Germany, especially Miro Zara artist and director.

A special thanks also to Ortwin from the Red Cross in Grevesmühlen and to participants from the immigration center in Upahl / Kunst Kollektiv Upahl their involvement and generosity made this project possible!

Thank you to the people from “Die Ecke” Community space and teenagers participating from “The Matrix” Youth Center, alongwith the Municipal Museum in Grevesmühlen for the conversations, time, and perspectivesthey shared along the way, and Big thanks to the art residency Schloss Plüschow in Mecklenburg Vorpommern north Germany, especially to Miro Zara, her support along the way, was really important in allowing this project to take shape.

Thanks to all of you for helping me understand and for sharing your voices from unexpected angles