Transient

Rebekka Kühnis

Gallery 3

7th of February – 23rd of August 2026

Someone went walking. He could have taken a train and traveled into the distance, but he only wanted to ramble about nearby. Things near seemed to him more significant than significant and important distant things. Thus, to him, insignificance was significance. We don’t wish to deny him this.

– Robert Walser, Walking, 19141

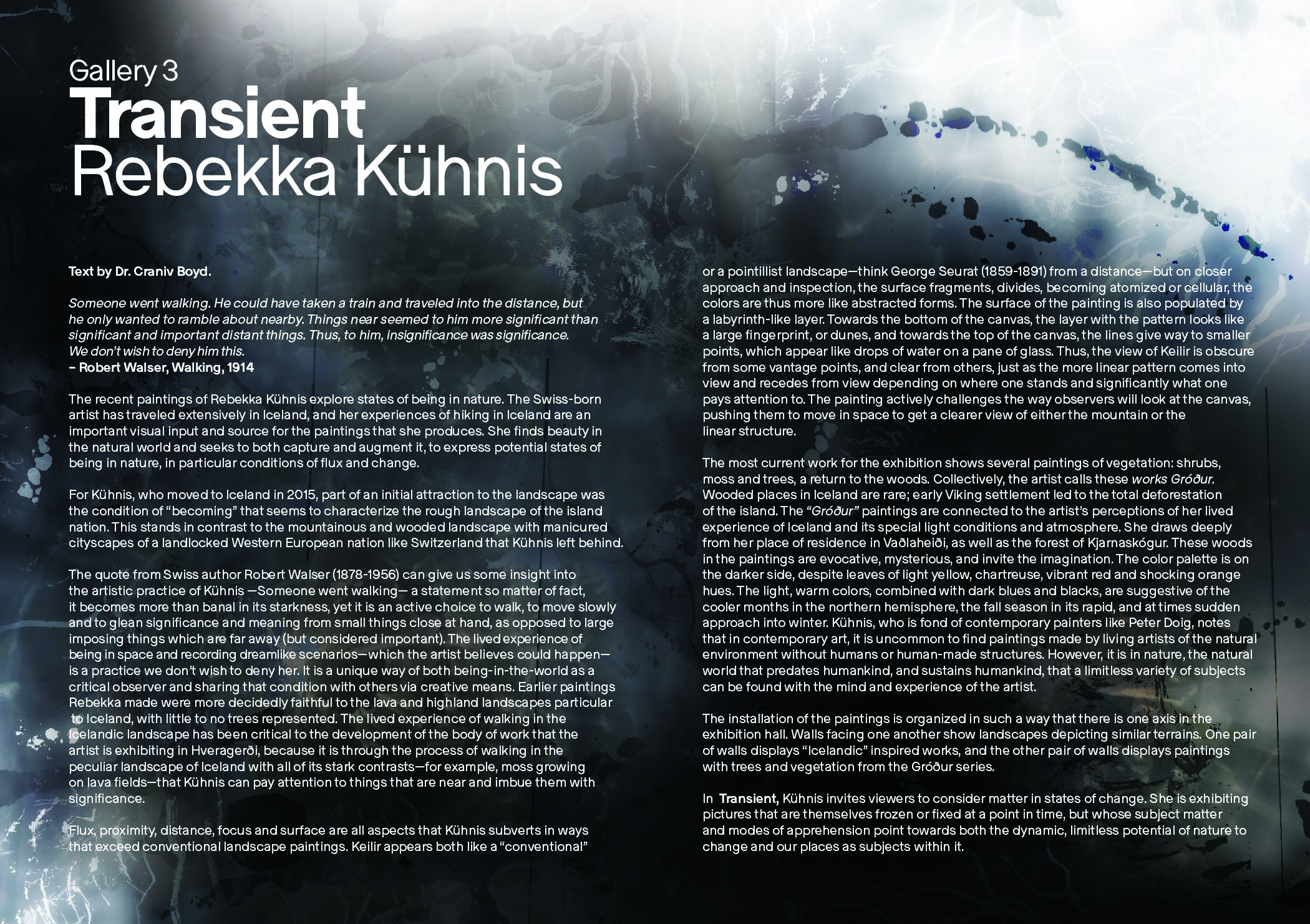

The recent paintings of Rebekka Kühnis explore states of being in nature. The Swiss-born artist has traveled extensively in Iceland, and her experiences of hiking in Iceland are an important visual input and source for the paintings that she produces. She finds beauty in the natural world and seeks to both capture and augment it, to express potential states of being in nature, in particular conditions of flux and change.

For Kühnis, who moved to Iceland in 2015, part of an initial attraction to the landscape was the condition of “becoming” that seems to characterize the rough landscape of the island nation.2

This stands in contrast to the mountainous and wooded landscape with manicured cityscapes of a landlocked Western European nation like Switzerland that Kühnis left behind.

The quote from Swiss author Robert Walser (1878-1956) can give us some insight into the artistic practice of Kühnis —Someone went walking— a statement so matter of fact, it becomes more than banal in its starkness, yet it is an active choice to walk, to move slowly and to glean significance and meaning from small things close at hand, as opposed to large imposing things which are far away (but considered important). The lived experience of being in space and recording dreamlike scenarios—which the artist believes could happen—is a practice we don’t wish to deny her. It is a unique way of both being-in-the-world as a critical observer and sharing that condition with others via creative means. Earlier paintings Rebekka made were more decidedly faithful to the lava and highland landscapes particular to Iceland, with little to no trees represented. The lived experience of walking in the Icelandic landscape has been critical to the development of the body of work that the artist is exhibiting in Hveragerði, because it is through the process of walking in the peculiar landscape of Iceland with all of its stark contrasts—for example, moss growing on lava fields—that Kühnis can pay attention to things that are near and imbue them with significance.

Flux, proximity, distance, focus and surface are all aspects that Kühnis subverts in ways that exceed conventional landscape paintings. Keilir appears both like a “conventional” or a pointillist landscape—think George Seurat (1859-1891) from a distance—but on closer approach and inspection, the surface fragments, divides, becoming atomized or cellular, the colors are thus more like abstracted forms.3

The surface of the painting is also populated by a labyrinth-like layer. Towards the bottom of the canvas, the layer with the pattern looks like a large fingerprint, or dunes, and towards the top of the canvas, the lines give way to smaller points, which appear like drops of water on a pane of glass. Thus, the view of Keilir is obscure from some vantage points, and clear from others, just as the more linear pattern comes into view and recedes from view depending on where one stands and significantly what one pays attention to. The painting actively challenges the way observers will look at the canvas, pushing them to move in space to get a clearer view of either the mountain or the linear structure.

The most current work for the exhibition shows several paintings of vegetation: shrubs, moss and trees, a return to the woods. Collectively, the artist calls these works Gróður. Wooded places in Iceland are rare; early Viking settlement led to the total deforestation of the island The “Gróður” paintings are connected to the artists perceptions of her lived experience of Iceland and its special light conditions and atmosphere. She draws deeply from her place of residence in Vaðlaheiði, as well as the forest of Kjarnaskógur. These woods in the paintings are evocative, mysterious, and invite the imagination. The color palette is on the darker side, despite leaves of light yellow, chartreuse, vibrant red and shocking orange hues. The light, warm colors, combined with dark blues and blacks, are suggestive of the cooler months in the northern hemisphere, the fall season in its rapid, and at times sudden approach into winter. Kühnis, who is fond of contemporary painters like Peter Doig, notes that in contemporary art, it is uncommon to find paintings made by living artists of the natural environment without human-made structures. However, it is in nature, the natural world that predates humankind, and sustains humankind, that a limitless variety of subjects can be found with the mind and experience of the artist.

The installation of the paintings is organized in such a way that there is one axis in the exhibition hall. Walls facing one another show landscapes depicting similar terrains. One pair of walls displays “Icelandic” inspired works, and the other pair of walls displays paintings with trees and vegetation from the Gróður series.

In “Transient,” Kühnis invites viewers to consider matter in states of change. She is exhibiting pictures that are themselves frozen or fixed at a point in time, but whose subject matter and modes of apprehension point towards both the dynamic, limitless potential of nature to change and our places as subjects within it.

Text by Dr. Craniv Boyd.

1) In Robert Walser, Little Snow Landscape and other stories, translated by Tom Whalen (New York: New York Review Books, 2021).

2) The artist draws on comments made by American artist Roni Horn about Icelandic nature having an unfinished character or a condition of a constant state of “becoming.” Additionally, the unfinished quality of becoming is an important concept with influence on aesthetics developed in part by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in A Thosand Plateus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

3) This effect of proximity and distance and representational pictures that disintegrate into abstract patterns was also used by the late American painter Chuck Close (1940-2021), who due to paralysis could only paint from a wheelchair and with limited use of his right arm. Close continued with a modular grid with various color values to generate at times large-scale portraits. Kühnis has a more open-ended approach to the disintegration of her pictures depending on vantage points of the viewer.