Aerials

Hrafnkell Sigurðsson

Gallery 1

2nd of March – 25th of August 2024

Dr. Halldór Björn Runólfsson

Nature is not only encompassing it also resides in us preventing us from distinguishing clearly between outer reality and inner perception. This is why Hrafnkell Sigurðsson is preoccupied with nature as the one who realizes that he belongs to it completely. He pitches his cusped, prominent tents – foreign elements in style of symmetric space laboratories or oriental pagodas – in front of the snow-white surroundings. His whimsicality towards nature is characterized by a provocative boldness whereas the surroundings cannot assume his orderliness and must consent to a position of a neutral background to his staging. Our inner nature is however amply revealed in Buchers´ Duel, a video of two symmetric butchers, holding on to hooks in mid-air as fighting Samurais dressed in pastel coloured freezing plant outfit against a black background, ready to attack one another with long daggers, which however never touch.

Another challenge appeared in 2024 in form of Aerials, as continuation of Freeze Frame, a video loop installation on five LED screens exhibited in Ásmundarsalur, Reykjavik, in 2020. Both series are the result of innumerable climbing to the summit of Mount Skálafell, dating back to 2017, where the snow laid aerials and the sculptor’s supporting iron rods covered in clay seems obvious. The difference is that Hrafnkell is not involved with the modeling but satisfies himself with documenting the attacking snowdrift, the result of nature’s elements thus approaching creation itself yet avoiding any appropriation of its product.

Hrafnkell Sigurðsson (b. 1963) lives and works in Reykjavik. He graduated as Master of Arts from the Goldsmiths College in London, in 2002, after studies at the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht, 1988-1990, and the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts, 1987. According to himself, he provides the structure on which nature relies, photographs it and processes in a computer, partly assisted by artificial intelligence. The human hand, nature’s elements and digital technology are combined in a complete process where the final result appears in the form of photographic works.

In 2023 Hrafnkell Sigurðsson received the prestigious Icelandic Visual Art Award.

Here you can visit the exhibition in 3D.

https://my.matterport.com/show/?m=3duRTyQrKJr

https://www.hrafnkellsigurdsson.com/

————————————————————————————————————————————————

On the Rhizomatic Nature of Hrafnkell Sigurðsson’s Aerials

Dr. Craniv A. Boyd

“Becoming is a rhizome, not a classificatory or genealogical tree. Becoming is certainly not imitating, or identifying with something; neither is it regressing-progressing; neither is it corresponding, establishing corresponding relations; neither is it producing, producing a filiation or producing through filiation. Becoming is a verb with a consistency all its own; it does not reduce to, or lead back to, ‘appearing,’ ‘being,’ ‘equaling’ or ‘producing.’ […] A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo. The tree is filiation, but the rhizome is alliance, uniquely alliance. The tree imposes the verb ‘to be,’ but the fabric of the rhizome is the conjunction, ‘and… and… and…’ This conjunction carries enough force to shake and uproot the verb ‘to be.’”

— Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 1987

The rhizome is a key concept developed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their second instalment of Capitalism and Schizophrenia, an experimental treatise that uses schizoanalysis to describe the organizing principles of society, psychology, literature, music, and art. As a structural model that branches out and conjoins disparate elements, it seems to me an apt notion with which to approach Aerials, Hrafnkell Sigurðsson’s latest series of works, in trying to understand how they are and remain in a state of becoming and interbeing. Indeed, I would suggest that they are rhizomatic insofar as they are woven from the fabric of conjunction, fashioned by a process of “and… and… and…,” and resisting imitation or identification with something.

Sigurðsson does not live and work in a vacuum, and much of his artistic output reflects, refracts, and augments mundane objects (Icelandic ships, crewman, trash bags, plastics). By means of photography and digital manipulation, he renders the familiar uncanny: In Revelation, bubble wrap is submerged in water and floats ethereally, while in Resolution, footage from the Webb telescope is blown up, pixilated and displayed on LED billboards across the greater Reykjavík area. The paint on the side of a ship is thus rendered into a photographic print that calls to mind the matter-of-fact minimalism of Bernd and Hilla Becher or the color field paintings of Mark Rothko. The ordinary bubble wrap and the process of submerging the plastic in a lake, then diving to photograph it in a suspended state, brings viewers into a relation with familiar materials in an unfamiliar terrain. The aquatic setting lets the industrially produced material become almost organic, as if it were cast-off skin from some giant reptile. The captured light of heretofore unthinkably distant stars and galaxies is tweaked and adjusted to become an even more mysterious and baffling visual field. The results of this rigorous artistic, if not scientific, experimentation is then inserted back into the community via their public display on billboards: art as light without captions and without explanations. For Sigurðsson, these processes of transformation and becoming are part of the connective tissue of what he does. The uncanny nature of his work, combined with the actual objects through which it manifests itself, prompts viewers to question the nature of what they are seeing.

This questioning is a game of abduction between the artist and his viewers, as theorized by the anthropologist Alfred Gell in his posthumously published book Art and Agency. Gell contends that viewers of artworks try to guess not only what art objects are but how they are made. Art objects, their makers, and their viewers are thus caught up in a nexus that he describes as a technology of enchantment. In Aerials, viewers must use abductive reasoning to establish what the photographs represent, yet their appearance and the process by which they are made remains elusive. This is partly because of the ‘enchanted’ technologies (cameras, computers, artificial intelligence) that Sigurðsson uses to create his own version of enchantment.

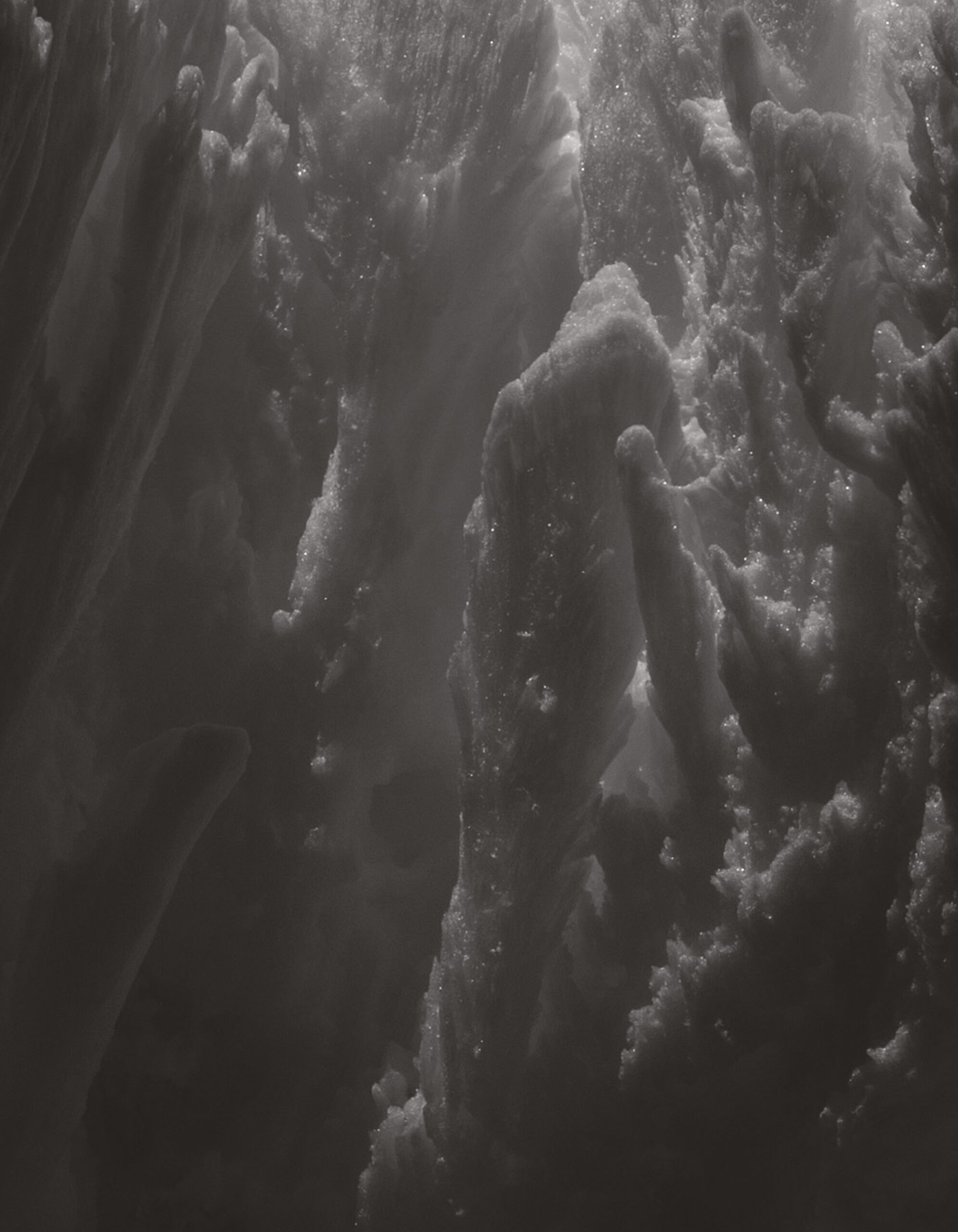

The objects at hand are a suite of large photographs of frozen, wind-blown water that has accumulated on steel aerials fabricated and placed by the artist on Skálafell Mountain. Some prints are framed behind protective glass, others are hung directly on the wall, and still others are bracketed by an interrupted line of either bright orange or black tape. One photograph is wrinkled and floats at a small distance from the wall. Additionally, there is one color photograph that provides clues as to how the series was made. It shows a Cerulean blue sky, white frozen water, and a hint of a steel armature. In the lower left corner is a sliver of a mountain landscape, to the right of the armature covered in snowdrift is a trail, or what the artist calls a “digital echo,” generated with the help of AI software. The remainder of the photographs are black-and-white or greyscale. The frozen water could be cloud formations, and cosmic nebula, and coral reefs, and caves, and microscopic phenomena (as in a previous work titled Concrete Conception). The Aerials seem to have no beginning or end; like the rhizome, they are between, in the middle, and the frozen moments captured on film could be moving or, at the very least, represent things in flux.

The larger Aerials are framed by broken lines of tape. In some instances, there are more than a dozen pieces of tape framing the work, in others, as few as four. Their jarring lines suggest tension, perhaps inducing the kind of push-pull spatial effect that Hans Hofmann elicited in his abstract paintings. The physical size of the photographic prints is considerable, confrontational, forming an imposing field that literally envelops viewers. That terrain is further expanded by the generative AI used to augment the original photographic source material. This is nature, but “blown up” – a twenty-first century aesthetic rooted in the Kantian notion of sublime. The smaller works in the series have a more haptic feeling – in fact, the smaller the scale, the more figurative and malleable the individual motif seems. Some emerge from an atmospheric realm, whereas others are set against near total darkness, adding a stark relief to the textures of the frozen water.

The rhizome that is Aerials consists of elements and procedures that Sigurðsson selects and combines into a process of becoming. Subjecting hand-fashioned sculpted metal objects to the forces of the harsh mountain climate of Icelandic winter, documenting these devices left to gather frost, editing the resulting images, applying generative AI to create “digital echoes” – these are the main stages of an additive process that the artist continues in the museum space by determining the size and placement of the prints. Its cumulative effects provoke and bring to life a technology of enchantment where viewers decode the work, are enveloped by it, and engage with processes of transformation and becoming that the artist sets in motion by being what he calls “creative while a part of creation.”