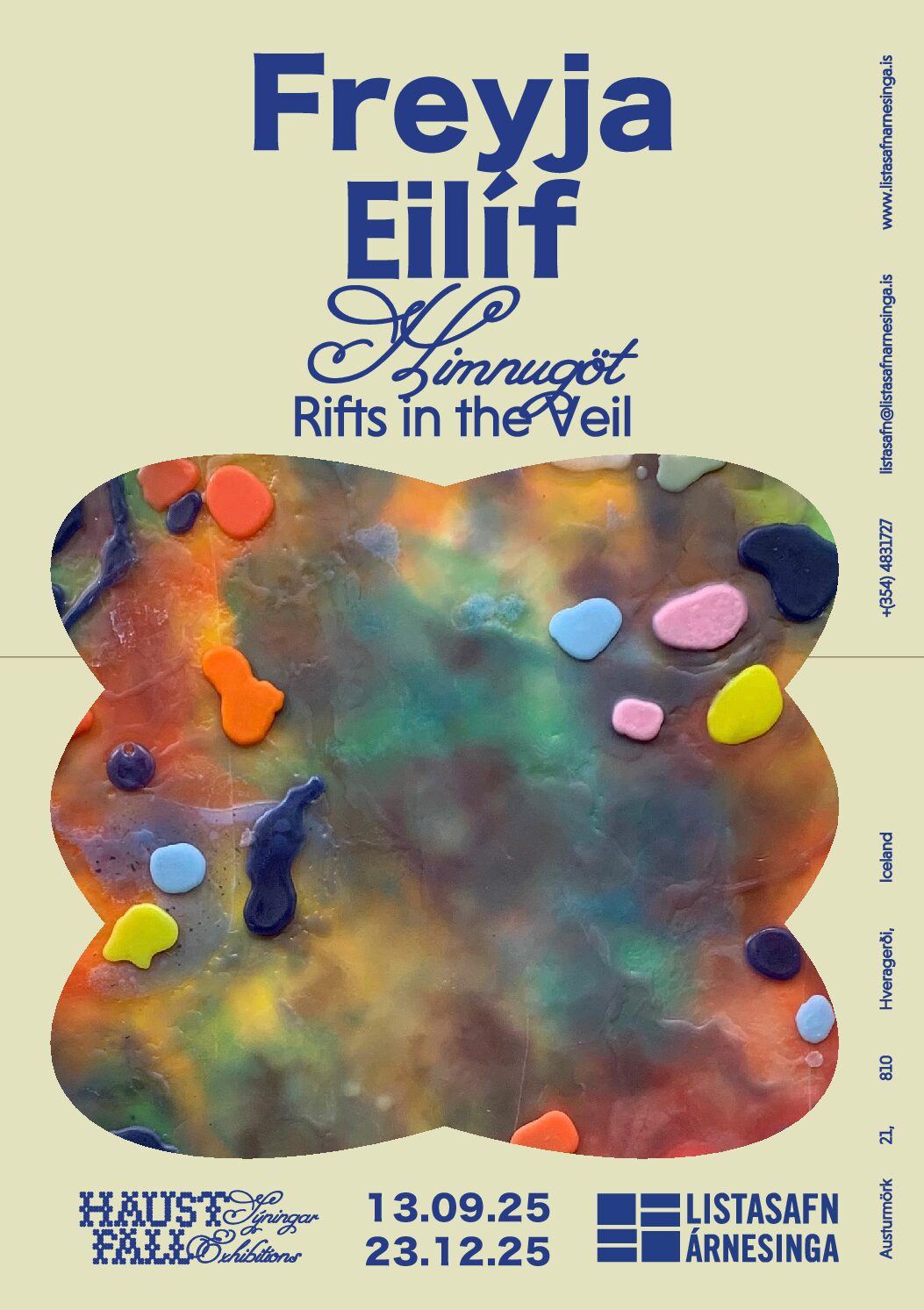

Rifts in the Veil

Freyja Eilíf

Gallery 2

13th September – 23th December 2025

Travels in Many Worlds

Jón Proppé

Break on through to the other side

Break on through to the other side

Break on through to the other side, yeah

– Jim Morrison

Since completing her studies at the Icelandic Academy of the Arts, Freyja Eilíf has produced a variety of artworks, including artist’s books, sculptures and performances, often relaying urgent political messages. In recent years, she has come to concentrate more on what might loosely be called the “spiritual”. Her explorations, however, are both rigorous and exhaustive and she has travelled to North-America to study with Native-American shamans, in addition to studying the shamanic traditions of other nations. This research has gradually come to inform more of artistic practice and the present exhibition is a step on that journey.

It is not easy to tackle such subjects when contemporary society is largely dominated by a narrowly-focused mechanical rationality, originating in the Western societies, that firmly rejects the traditional wisdom of other peoples and sees shamanism and the worship of nature as being only childish superstitions. This view is only a few centuries old, however, and mirrors closely the colonial expansion of the Western powers. It is much easier to subjugate other nations and plunder their resources when you have convinced yourself that they are composed of childish idiots and dangerous devil worshippers. Yet we have clear evidence to show that shamanisms and the worship of nature have been the common practice all over the world for at least 40,000 years and that people got on perfectly well with such practices. Conversely, we can now see ever more clearly what the spread of Western influence with its mechanistic philosophy has been: Whole nations have been driven off their lands and reduced to poverty, if not simply eradicated, and the rape of the natural world has been so merciless that it has become ever more uncertain whether mankind can survive at all.

A long time ago, most peoples developed the idea that the universe in fact consists of three worlds: There is the present world where humans live, the upper world which is the abode of the gods, and the netherworld where the dead reside. These worlds are separate, yet somehow connected along a common axis. The separation is not absolute, furthermore, as openings can be found in the membrane that divide them. This explains how the gods can keep and eye on the human world and even enter it on occasion, as Odinn did in the Nordic tradition and as seems to have happened quite frequently in the Greek and Roman worlds.

Of course, people did not believe that these worlds were literally like three disks, pierced by a single pole or nail. That would be childish because the description is obviously a metaphorical one. The division of the worlds is not geographical and not even physical at all: It is a spiritual one. We all sense that there must be something “beyond” our everyday experience, something that often influences our world but that we have a hard time pinning down. Under this world view, everything depends on maintaining a proper balance. It is best, for example, that the dead go directly to their world and stay there, rather than continuing to roam the human world, going bump in the night. If the balance is upset, actions must be taken to restore it, perhaps through some kind of exorcism where roaming spirits are sent back to their proper place. This, in turn, requires knowledgeable persons who can undertake such dangerous tasks. Disease and pestilence can also upset the balance and must be cured, and peace must be maintained among humans. Nature must also be treated with care and respect, again to maintain the proper balance. As a result, all peoples have designated persons to oversee these matters and restore balance when needed, persons who preserve the culture and the ancestral knowledge in order to resolve problems and ensure both the physical and spiritual well being of society. These are the shamans.

The Western colonialists could not accept that shamanic practices are a perfectly legitimate way to seek knowledge and understanding – there is nothing suspect or mysterious about them. To solve a problem, one must first think about it. In the West we might draw a flow chart or program a “mind map” on the computer. The shaman might toss bones or carved figures on the skin of his drum which has been decorated with images and symbols representing the history and world of his people. We can easily see the making of flow charts as a kind of ritual and, conversely, construe the shaman’s actions as a scientific investigation; both are a way to think about and understand the problem at hand. Both can perhaps be seen as analogous to when we rearrange our letters during a game of Scrabble in the hope of finding a word we can use.

The idea of hidden worlds, separated by a porous membrane, is first and foremost a way to organise knowledge and understanding. The shaman knows that there are things we do not see or know about, but that nonetheless play a role in maintain the necessary balance in our world. To gain an understanding of this, the shaman must in some sense abandon him- or herself, to think outside the box that is the everyday world. Sometimes this involves a trance and there are innumerable accounts of a shaman dropping to ground and lying there, even for hours or days, while his mind travels through the hidden worlds in search of answers and solutions. The world “trance”, used in most Western languages, derives from the Latin word transire which means “to travel across or though”. Trance is a method for slipping through the pores in the membrane that separates our world from the others. The problem with the Westerners’ way of thinking is that they believe themselves to already possess all the answers. They therefore go about without any thought of maintaining balance and the consequences of their action come as a complete surprise to them, usually when it is too late to turn back.

It is not out of sheer curiosity that Freyja Eilíf has made these questions the focus of her investigations and of the art. She has an urgent message to convey because it is ever more important that we learn to resist the Western misconceptions which, along with the race for endless expansion and more resources to plunder, are bringing us ever closer to a total catastrophe. It is only proper that she conveys her message though art because it is precisely the role of the artist cross boundaries, to take the risk of abandoning our safe certainties and embrace the unknows – like a shaman in a trance – in an attempt to bring us a new understanding of ourselves and our world.