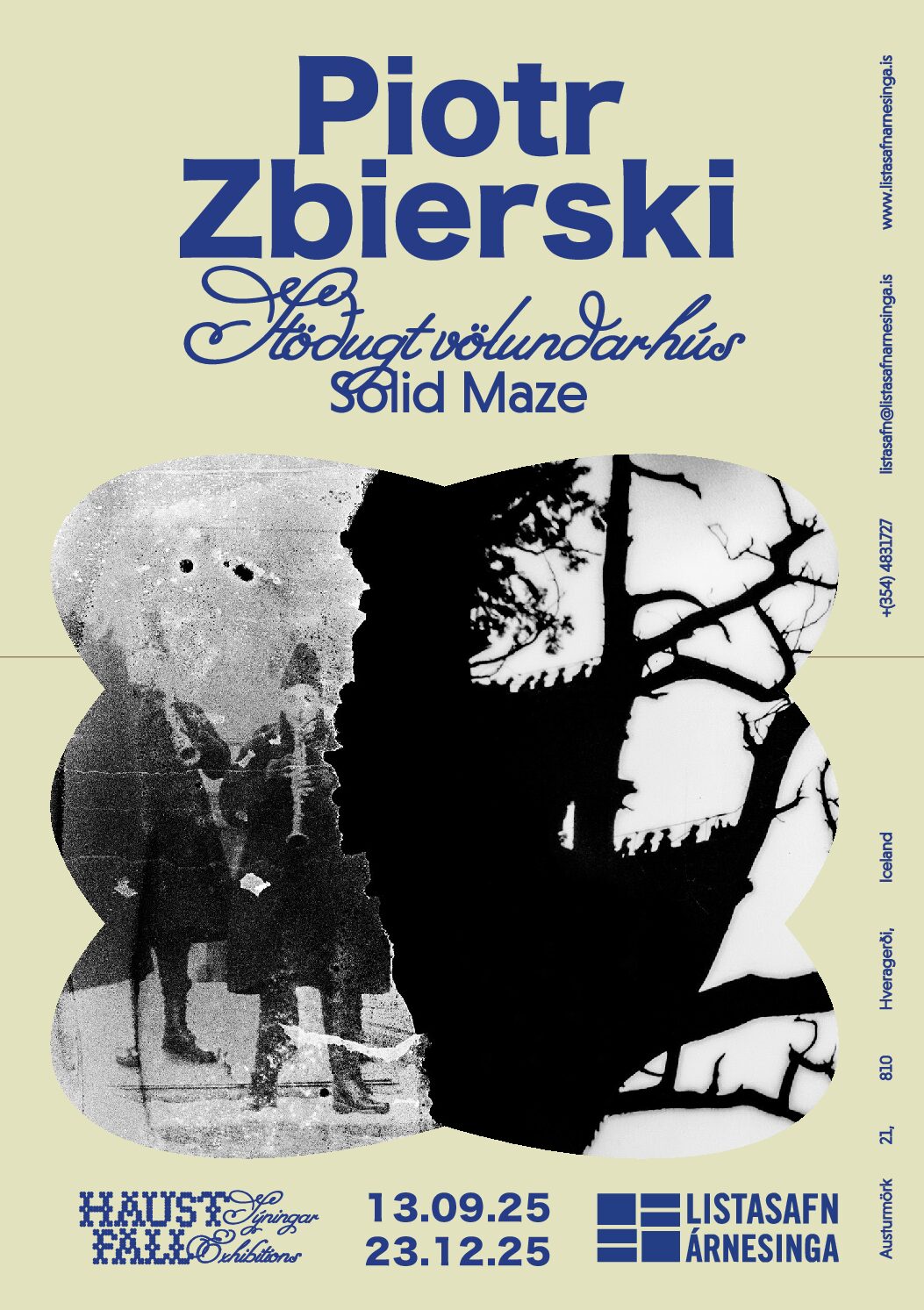

Solid Maze

Piotr Zbierski

Gallery 4

13th September – 23rd December 2025

Text by Erin Honeycutt.

Time is a place. Time is love. Where do you stop and take a look around?

Time is a place. Time is love. These words linger as more than metaphor; they suggest that time is not only something we move through, but something we inhabit. Time has texture, atmosphere, even emotion. In this framework, memory isn’t a retrieval of something lost but an ongoing negotiation with what continues to live in the background of perception. Time opens a space, and love fills it.

At the heart of Piotr Zbierski’s work lies a meeting of relationships with different intervals of time, a continuum of nuances rather than dualities that mirror the simultaneous lyricism and violence of existence and invite us to consider how disparate sensations, feelings, and events collide within the body, and can only be re‑woven into unity through art. Zbierski—whose practice spans photography, print, collage, and archive—asks: where does lived experience end and narrative begin? His lens traces a river that carries us between two shores: one of polished stories, the other of raw memory. The result is a maze of possibilities across a long arc of time, forwards and backwards, deep and wide; both a structure and a metaphor, evoking labyrinths, animistic forms, and glacial memory.

I keep returning to a conversation with Piotr about his day job in Iceland as a lifeguard at a public swimming pool. That detail struck me. There is something resonant in the pairing: the lifeguard and the photographer. Both are quietly attentive figures, stationed at thresholds. They hold vigil at the edge of visibility, trained to notice what others don’t. To take a photo or to save someone from drowning both require a particular type of awareness. A readiness to act at the precise moment something slips from the surface. The lifeguard must sense distress before it’s declared; the photographer must sense an image before it fully appears. Both disciplines are about seeing what isn’t fully seen and acting at the right moment.

I think about the camera as being the ontological opposite of the gun in Paul Virilio’s War and Cinema, a suggestive analysis of military “ways of seeing” and the convergence of perception and destruction in the parallel technologies of warfare and cinema. How the weapon and the armor evolve together, as do visibility and invisibility begin to evolve together, eventually producing invisible weapons that make things visible. Can this tool be taken out of this historic framework of power to become a tool of relation, a tool more akin to a language? I follow this logic and think about the sun and if this analysis works in an analogy without humans.

The act of documenting can become a form of rescue, of holding space for what might otherwise disappear. Photographic practice, especially in Piotr’s Solid Maze of All That’s Left Untold, seems to operate on this quieter frequency. There’s a slim, barely perceptible thread that runs through the work, tying together the seen and the sensed, the visible and the vanishing. The photographs are not declarations, but something more akin to clues. Traces of presence, of feeling, of memory not yet fully formed.

There’s a question embedded in the work: Can the solid be unsaid? What happens when something we think of as fixed—stone, structure, the body—is shown to be porous, impermanent, or emotionally unstable? In Piotr’s images, solidness often functions as a kind of void, a container for what can’t be articulated. The negative space in a photograph isn’t empty; it’s charged with potential. It asks the viewer to complete a gesture, to enter the image not just with sight, but with thought, memory, and speculation. This is the kind of ekphrasis that doesn’t merely describe—it listens.

In one photograph, we find handwritten notes functioning like equations:

love + self = (sunshine symbol)

no love + self = (star symbol)

love + no self = (moon symbol)

soul (crossed out with spirit written below) + body (crossed out with soul written below) = (human stick figure symbol)

These symbolic formulas suggest a search for language that precedes or exceeds logic. They’re not answers but propositions—mapping the tension between presence and absence, unity and fragmentation. Each equation reconfigures the relationship between emotion, identity, and embodiment. There is no fixed solution. Instead, what emerges is a desire to chart the affective conditions of being—what changes when love is present, when self dissolves, when the categories of spirit, body, and soul overlap or collapse.

Throughout the series, the viewer is guided by a recurring thread—light as both literal and metaphorical material. Light breaks through clouds, falls in narrow streaks over black rock, refracts in the glint of a man’s jacket, reflects off the curved surface of a globe held in hand. It finds its way into graffiti markings in a night alley, into the crescent edge of the moon peeking out behind a concrete pillar. It appears again in the handwritten script layered over the images—white on black—where language mimics the visual quality of light, fragile yet illuminating. Light becomes the thread stitching the work together: a connective tissue between the world, the image, and the mind of the photographer.

This interweaving of image and text, of material and memory, situates Walter Benjamin’s writing on the nature of memory. “Memory,” he writes, “is not an instrument for surveying the past but its theater. It is the medium of past experience, just as the earth is the medium in which dead cities lie buried.” To remember, then, is not simply to look back, but to enter into a dynamic space where history is staged, enacted, sedimented, in layers that must be carefully

excavated. Benjamin describes memory as an archaeological act. One does not simply recover a fact or a moment; one must dig, with care and humility, as though handling fragile ruins.

In this sense, the photographer becomes a kind of digger—sifting not through dirt but through atmosphere, gesture, light. Similarly, the lifeguard is attuned to small shifts in pattern or temperature, watching the surface for anomalies that might signal distress below. These practices share an ethics of attention. They require stillness, patience, presence. To photograph is not to capture but to hold. To guard. To say: I saw this. I stayed long enough to notice.

What Piotr’s work proposes is that photography might be less about fixing time and more about entering it. Less about memory as object and more about memory as medium—as the space in which meaning continually re-forms. His images do not explain; they attend. They open up a borderland where image and language, memory and feeling, thought and intuition begin to overlap. And in that overlap, something numinous begins to emerge—something not entirely nameable, but profoundly felt.

In the end, what remains is not just the image, but the act of looking itself. The held gaze. The breath before the shutter. The silence between two swimmers in a pool. The light spilling between clouds. And the viewer, pausing just long enough to feel what the image never quite says, but always contains.