CHALLENGE

January 24 – April 23, 2015

Ásthildur Björg Jónsdóttir

We all want to live the good life, but we don’t all have the same views on what constitutes a good life. Family, friends, good health, cultural diversity, security, independence, financial security, a wholesome and beautiful environment, empathy and love are elements in our lives that together constitute our well-being. In order to create the appropriate conditions for a good life many different issues and how they relate to one another must be carefully considered. We understand that spending beyond our means will end in having to pay off our debts. In the same way, by maintaining the limited perspective of short term economic growth we endanger the quality of life for future generations. The key to sustainability is to find a balance in our ‘good life’ that does not endanger the quality of life of present and future generations.

All the artworks in this exhibition relate to the discourse on sustainability and the ethical issues involved in a society’s development. Sustainability includes overlapping environ- mental, economic, cultural and social factors. Changes within each factor can always affect the other and development can only be sustainable if it takes into account all these factors. It is important to keep in mind the benefits and need for sharing of common resources that need to be protected and utilized in a sensible way. In such a society one’s living standards are not achieved at the cost of others, nor does it reduce opportunities to improve living standards. This is why we should ensure that we do not exploit natural resources beyond their capacity to renew themselves. Amongst our greatest challenges is the need to adapt economic development to environmental and social realities. Natural resources are invaluable, providing services that humans cannot live without, and it is therefore paramount that people understand the importance of their preservation. When we discuss environmental issues it is always useful to do so from the perspective of society as a whole.

There is a clear connection between culture and sustainability, as culture can influence behaviour, consumption patterns and production modes. Knowledge is a necessary premise for a more sustainable society and is the building block on which we construct our values and make our decisions. Most people value knowledge and truth thus enabling them to deal with complicated circumstances in their natural or built environment. With increased knowledge of the world we can learn about connections in nature. Knowledge enables the individual to discover his own part in the natural world and in society, making it possible for him or her to make connections between different events and see them in context, as part of a whole.

The artworks in this exhibition Challenge offer a range of interesting situations that are worth looking at in the con- text of sustainability and raise questions regarding man’s connection to nature. Context and knowledge are necessary in order for us to participate in countering the dangerous consequences of man’s unsustainable behaviour and its negative effects for future generations. To achieve change we must participate in society and act collaboratively.

Wicked Problems

Unsustainability in the present and in the past is often the cause of society’s wicked problems, frequently connected to cultural or social factors which makes them difficult to resolve. The solution is hard to find and not right or wrong but may appear as either a positive or negative development. This is because we cannot foresee the problems that arise; our attitudes towards them vary; different individuals with dissimilar perspectives are involved in the problems to which there are many solutions and their effects are based on different values.

The artworks in this exhibition are connected to wicked problems. By contemplating their subject matter we may become aware of other places in the world and the impact we have on far flung places. The exhibition Challenge provides viewers with the opportunity to consider and even debate these situations and the issues which arise. In this manner, the artworks question assumptions that are generally accepted as true without looking for counter arguments. LÁ Art Museum thus becomes an arena to help us raise questions, creating a space for discussing the tensions within the world and exhibiting works that themselves are connected to our experiences.

The exhibition’s objectives are to provide us with the opportunity to discover issues related to sustainability and raise related questions on sustainability, us and the various values we hold. The guiding principles behind the choice of artworks were to provide an artistic perspective from which we have an opportunity to get to know the issues of sustainability and to raise questions on important issues of sustainable development that concern all of us. The content of the work thus raises questions that help us interpret the work on our own terms and thus provide us with fresh tools to consider views and messages portrayed in these creative works.

How can we learn from Artwork?

In a society that strives for sustainability it is important to observe and value different forms of knowledge. Creating art is not a meaningless exercise. Instead, one might say that works of art serve as a window that interprets the world. The qualities of the works chosen for this show provoke critical thinking and encourage us to take a stand on the issues discussed, and even demand our participation. Artworks of this kind are well suited to help us understand the issues we face regarding sustainability. The connection between the artworks exhibited and the discussion of single works reveals issues connected to sustainability such as ecology, the environment, equality and philosophy from diverse perspectives. The works raise questions of who we are, what we prioritize in our lives, the world surrounding us and how we behave and the impact our behaviour has on our environment and our society. Artworks that initiate a discussion of the social situation of the individual, the connection between man and nature, attitudes, values and national self-identity or gender roles have the capacity to raise our interest and challenge our perspectives.

Encounters with Nature

Some of the artworks inspire us to think about the connection between man and nature. How do we utilize our resources? What are the consequences of inaction? Inaction can be expressed in laziness, lethargy or sloth leading to a waste of resources. Ethical questions are also deeply connected to social factors that are the foundation of a sustainable society. These factors often relate to arrogant decisions made without consultation and in bad faith. Pride has many expressions, both individually and within society. Decisions are based on knowledge and consideration of the consequences of actions in time, place and for the future. It might be necessary to put personal ambition aside and take the time necessary to understand the situation before embarking on the next steps. These steps could focus on universal rights and the responsible use of resources. Those who practice such methods work in the spirit of humility, modesty, and transparency, guided by empathy, equality and consideration. Equality has many aspects that all have in common that they demand empathy, concern and consideration. But the consequences of ill-considered decisions are often overwhelmingly problematic and therefore it is difficult to determine what might be the best solution.

Most of us who travel around Iceland are dazzled by the beauty, magnificence and diversity of the landscape, if we give themselves time. In a modern society there is much that absorbs the mind that we often don’t give ourselves time to enjoy what we see.

The work of Eggert Pétursson highlights the beauty of small things. We often don ́t have to go far to experience nature ́s grandeur. „A painting is a painting, not a flower. Although my paintings show certain varieties of flowers and I try to be true to botanical details these are not the actual flowers. I also feel that a title excludes a variety of emotion- al experiences, it channels the work into a certain direction when I am trying to keep all options open. It ́s enough that people recognize the flowers in my work, I don ́t have to tell the viewer what their names are and even less so what frame of mind they should be in to take them in.“ (Pétursson, 2007)

The artist Rúrí is often political in her work. In many of her works she is concerned with the relationship between man and his environment and the effects of human actions on the earth. „Humanity seems to be constantly conquering nature, but there is no conquest of the earth: all we can conquer is ourselves by finding a golden balance with our environment. It’s the only realistic conquest.“ (Rúrí, 2011) The work Waterfall I-IX (2003) warns us not to over exploit our water resources that are an all important natural re- source.

Ólöf Nordal ́s work Iceland Specimen Collection,- Skoffin (2005) is based on a folktale about the mythical monster skoffín, that according to legend is an animal or distortion of an animal, a hybrid between a dog/cat and a fox. People feared the bastard offspring of different species because they were unfamiliar creatures. Similar fears exist in contemporary society towards the traditions and habits of ethnic minorities that are unfamiliar to us. Such fear equals racism. „Skoffín are terrible animals that can kill with their gaze. There is nothing cute or sweet about them. “ (Ólöf Nordal, 2015) The myth then became a reality when real skoffín were born in Flateyjardalur in the North sometime around the middle of the 18th century. The Icelandic Institute of Natural History decided to verify the truth of the tale by examining the conserved animal. Methods of DNA testing were used as in the case of criminal pathologists investigating an intended crime or paternity suit. DNA testing of the animal from Flateyjardalur was aimed at discovering the DNA of a dog or a fox. The result was that the animal proved to be a dog. In every instance of skoffin being detected in areas of the world inhabited by foxes it has been proven that this is only a case of natural genetic variations in the animal. In this work, Ólöf illuminates contemporary issues surrounding aberrations in humans and animals. The work invites both past and future references, as the idea of malformation has through the ages been a source of Icelandic folktales. In past centuries people were afraid of deformed animals and considered them of evil origin. In the work, Ólöf also points to the exchange between man and nature and man ́s efforts to control nature. In the past, Ólöf has explored other cases of malformation through natural circumstances. With her observations she emphasizes the diversity of nature and its sensitivity to the interference of man. It is also of interest to ponder whether we would rather believe the myth that flourished in Flateyjardalur, or the science of genetics that has obliterated our flights of fantasy on this mythical being that continues to exist even if only in our minds.

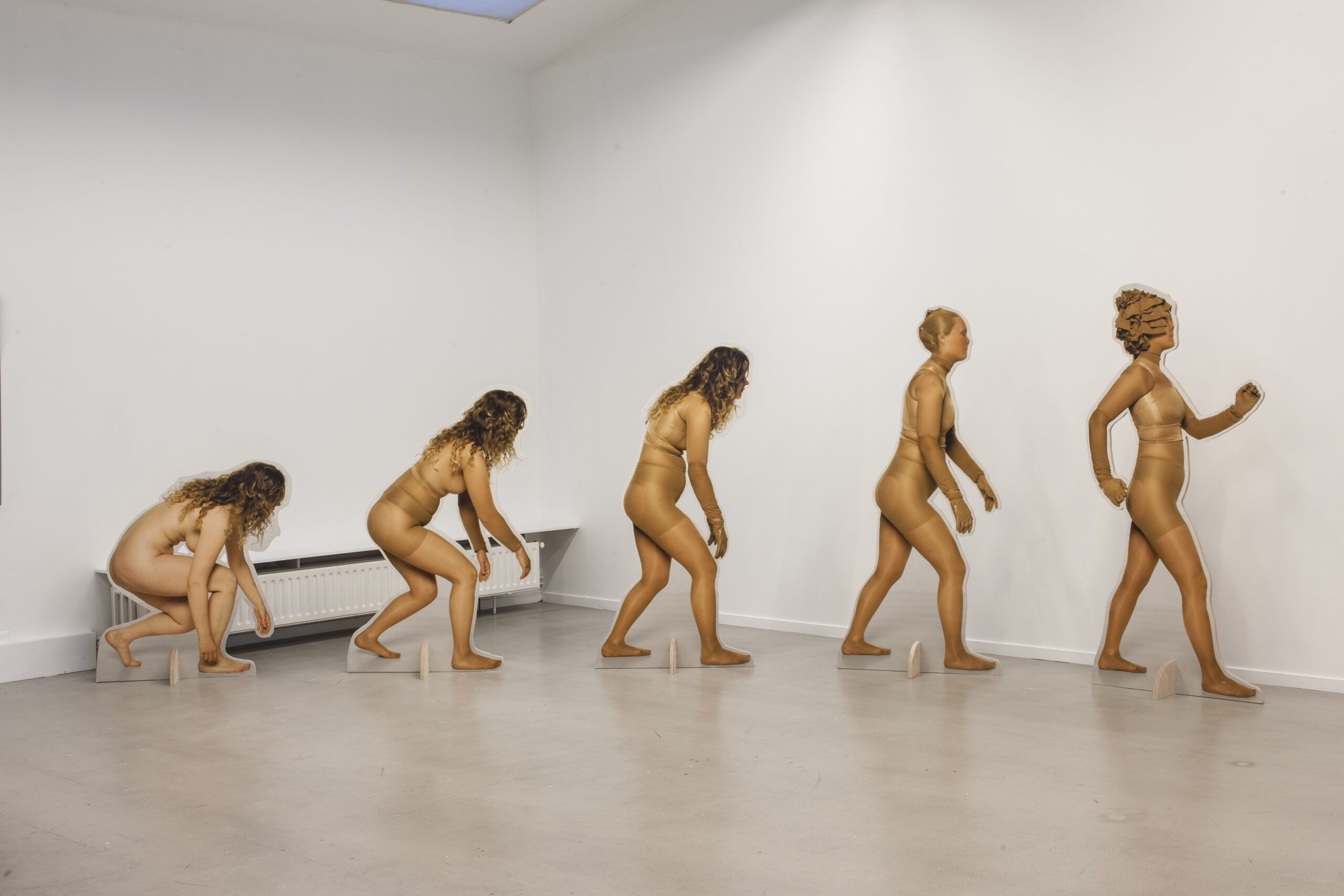

The Icelandic Love Corporation has also explored the problem of man ́s interference in the natural environment. In the work Attic and Evolution, we are given a chance to reflect on how far man has come from his origins. The work of the artist group is often focused on social and cultural factors, in which context the Icelandic Love Corporation has looked at globalization and pop culture. In their works, the artists often point at feminine factors and to accentuate these they use materials and methods often more connect- ed to women such as crocheting, sewing and textiles.

„While we think nylon stockings are an incredibly charming and important engineering feat they are also an example of how man tries to ́fix’ or ‘beautify ́ nature, for example, by producing stockings meant to push the butt up and the stomach in. We are also in touch with a producer who gives us leftover or faulty stockings. The nylon is derived from oil so that you might say that the stockings are our oil paints.“ (ILC 2015) In the natural environment the transformation of biomass to oil is a lengthy process. Overharvesting of oil results is an unsustainable use of natural resources. Like other plastic material nylon takes a very long time to break down and the waste creates problems.

This group of artists operates according to a democratic framework without rules and where nothing is beyond their consideration.

Man ́s Impact on Nature and the Environment

Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir ́s work, You have a face with a view (2011) shows how outside market forces have marketed chosen areas of Iceland. Society moves at a fast pace and often it feels like we must obtain everything at once. The portraits are a collage of postcards that Þorgerður uses to interpret the model ́s character traits. The work ́s title comes from a Talking Head ́s song, ‘This Must Be the Place’ from 1983, but the song includes the lyrics “Out of all those kinds of people, you’ve got a face with a view. „The work can also raise questions about the fast growing tourism industry and the effects of increased pressure on the natural environment. The over abundance of images showing the natural environment encourages people to develop a romantic fantasy of certain sites. Places that belong in Jules Verne and William Morris science fiction narratives. This island is a fantasy but still you want to believe every landmark and every adjective.“ (Ólafsdóttir, 2015)

In her work, (Un)foreseen (2014), Destination Ásdís Spanó, has developed her own working methods for the sustainable use of materials. Instead of using traditional oil paint and oil mediums, which by their nature are polluting for the environment, she uses a mixed technique with environmentally friendly materials. At the same time, she reflects on the unforeseen consequences we face as a result of the impact we have on nature. „I connect the lines to time and the multi-layered reality that characterizes the urban structures of the Western world. Linear horizontal surfaces penetrate the organic texture of the picture plane and merge with it just as man-made environment intertwines with nature.“ (Spanó, 2015)

Revelation by Hrafnkel Sigurðsson is a photograph of a bubble plastic wraps floating underwater. The work makes references to the culture of packaging. The bubble plastic is produced solely for protecting other manufactured items. Hrafnkell took the photographs in an Icelandic lake at about a depth of 10 meters. „At some point, I imagined that the packaging of the artwork itself would have been sucked into the surface of the photograph and remained there floating around.“ (Sigurðsson, 2014) Large quantities of plastic pieces are floating in the world’s oceans. Most of this plastic ends up in one of the five major garbage patches drifting in the oceans near the tropics, where the ocean currents gradually collect all loose floating objects in the area. Plastic can cause serious environmental and health risks throughout the food chain. The majority of plastic ends up as landfill with other waste, and it takes plastic in a landfill several centuries to degrade.

Various toxins that have been released into the environment, however, tend to settle on plastic garbage in our environment and do even more damage than they otherwise might. With this work the artist opens our eyes to what is important to us, and inspires us to think about what we need to change. This work raises questions about our consumption and its consequences. What sacrifices are we ready to make for our own consumption? In this work the viewers relate to daily consumption placed in a new context.

Rósa Gísladóttir’s work, The Doubt of Future Foes Exiles My Present Joy, describes the artist’s fear of the contamination of our natural environment caused by the habits of affluent society. “Our current well-being is bought at a high price because it entails environmental disasters that can be likened to enemies lying in wait in the future“. The work raises persistent questions about our consumption habits.

In her works, Rósa often explores double standards, where she looks at the gap between what is valuable and what we look at as garbage. „Maybe we have a love-hate relationship with packaging…. Everything taken on loan from the future is owed to future generations.“ (Gísladóttir, 2015)

Consumption is a complex phenomenon and the culprit is seldom one person. A country ́s consumption pattern can call for demands for heavy industrialization that is often seen to benefit certain social groups.

Pétur Thomsen works on the stamp man has put on his environment due to society ́s demands for increased economic growth and the demand for more production of electricity. In his series Imported Landscape he describes the drastic transformation of the landscape around Kárahnjúkar. From a subjective and dramatic viewpoint we observe the tracks man has left. The wounds made by the bulldozers are large and remind us to allow nature to enjoy the benefit of the doubt, as it has no defences

The installation by Bjarki Bragason consists of the video It, the paper work on it as it and the sculpture In it as it. The work is based on a piece of ice from Sólheimajökull found in a rubbish bin outside the cinema of the University after a scientific conference. The ice had been used to demonstrate how to use it to read weather periods and their history. In his artwork Bjarki looks at how values are created and investigates leftovers of valuable materials as a larger whole. Bjarki observed the ice as an object that is in the grey area between being an important scientific phenomenon used as evidence of time and history or as a piece of waste. In his attempt to approach the subject Bjarki cut the ice in two with a hot knife. One half he melted with a heat gun and the other half he sank into a concrete mixture that melted the ice through a coalescing chemical interaction.

The installation contemplates the insubstantial nature of the material and encourages us to ponder the chain of cause and effect on the one hand, and, on the other, the uncertain evidence of an event that has taken place and left its mark.

The power of knowledge by Anna Líndal by its very title raises a persistent question that motivates the viewer to ponder the power and responsibility that come with knowledge. „Understanding is a multi-faceted concept. Man’s understanding of how to split the atom, for example, brought him to ‘harness’ nuclear energy (1940), an example of the reciprocity between science and society in the twentieth century that many would have wished had not happened. Curiosity about one’s environment and the need to observe it, know it, and understand it, enables us to survive.“ (Líndal, 2015) When we learn and acquire know- ledge we develop ways of understanding. As we learn to live in harmony with others and the environment we need to be conscious of our own values and have the ability and knowledge that enables us to live with others. In this way, the nature and role of knowledge in society is complex and multi-layered.’ In her work, Anna responds to external factors, explores the tiniest units to examine the larger whole. She asks questions about cause and effect, looks at how historical authoritarianism is mirrored in our time, and how the primal energy that brings life to our lives surges in our everyday reality.

In the work, Can I offer you more I & II? Anna Líndal offers an interesting metaphor for how an ordinary action that breaks its boundaries becomes a threat to the ruling system. In this work we are given an opportunity to ponder the social position of women and the rules by which our daily lives are organized. Icelandic hospitality comes to mind, greed and how consumption can easily spin out of control.

Icelanders and Self-Identity

Libia Castro & Ólafur Ólafsson Untitled (Portrait of the artists wearing the Icelandic women’s costume; Peysuföt and Upphlutur) forms part of a large research project in which the artists make references to social and environmental injustice and the greed that characterizes today’s consumer culture. The work elicits an ethical perspective where we are encouraged to reflect on life and culture in connection with an emphasis on heavy industry in Iceland. In the work, the two artists stand in front of the first Icelandic aluminium plant. They reflect on the cost to the environment resulting from harnessing natural sources to produce electricity sold below market rate to heavy industry. Heavy industry is not only a threat to the country’s natural environment, but also to its culture and values. Criticism of our times is characteristic of most of Libia and Olaf ́s work. Here they use humour to highlight the importance of social re- form and thus provide us with an opportunity to exercise critical thinking concerning economic and political issues in Iceland.

Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir & Mark Wilson’s work, Icelandic Birds offers observations on the nature of categories and systems. How some things are easily categorized and invited to participate in a system while others are treated as uninvited guests. This is true both for human and animal relationships. The work invites analytical reflection on man ́s reluctance to change. It seems that innovation causes fear at the same time as the exotic is exciting. The work presents clear references to nationalism and invites us to ponder the directions in which society has developed and the increased emphasis on the myth of the ‘pure nation’, as well as the emphasis on cultural stability.

In this installation, the artists exhibit stuffed birds from Icelandic nature alongside a poster showing exotic birds whose natural habitats are warmer areas of the earth, but which have been imported into Icelandic homes as pets. It is interesting to approach this work bearing in mind how ideas about nations and nationalism have developed in the past and present, and how they might develop in the future. The international element is set against the local, nature against culture, what is accepted against what is forbidden. Reflecting on the origins of the pets leads us to think about when and how one becomes an Icelander since all these pets have inhabited Iceland, even for many generations, while many of the ‘Icelandic birds’ are migratory birds that only stay here for short periods at a time.

Ósk Vilhjálmsdóttir’s work Bónus can be interpreted as a critique of social injustice. In this work she interprets a true event in Icelandic history. It is based on a news photograph and painted in the style of propaganda posters from the beginning of the last century. In her work, Ósk often looks at contradictions, such as concepts from the business world and the connection between profit and loss – goodness and greed. She notes that these are ́vulgar ́ concepts people like to avoid using. Instead we use technical words that embellish reality, such as economic growth, laws of the market, ownership and consumer power. In her work Bónus, her subject matter is capitalist power and we are given cause to raise questions about the motivations behind charity. The work shows a merchant who has so much that he can give to those who have too little. In this sense it is worth asking why some people have too much and others have too little. In this image, Jóhannes in Bónus reminds us of the savior feeding the poor while the bishop blesses the event. The image is constructed as if it were portraying a sanctified moment, with its dark background and light focused on the giver. Its division into three parts recalls the structure of religious images.

We Can Make a Difference

Sustainability is a broad concept, and it is therefore difficult for all of us to understand whether steps in the right direction have been taken while the problems at hand can seem overwhelming. It is important that we all reflect on why we should and how we can concern ourselves with this issue. How can we create a society based on mutual responsibility? In such a society the inhabitants must take action, and know and be conscious of their values, attitudes, and feelings with regard to our global impact on the environment, as well as the equality for all the planet ́s inhabitants, nature and the environment, equality and diversity, well- being and public health, economic development and future vision.

In his series Weapons of the Revolution Spessi uses the style of the still life to show everyday objects like pots, pans, spatulas and kettles that protesters used in the Kitchenware Protests in order to express the injustices that the citizens of this country have to live with. The Kitchenware Protests rebelled against the ruling powers in society. The weapons reflect the individuals who wielded them, and therefore the photographs can be regarded as portraits. The weekly, even daily, protests were spurred by social activists in the aftermath of the banking crash in Iceland in the fall of 2008, and they continued into 2009. The series is therefore also a real source on these events and it accentuates the unexpected and historic meaning of everyday things in the context of protests against the worship of vanity.

Ásthildur Jónsdóttir ́s work Skúli ́s Crosses, All Around shows the quiet influence an individual can have on his environment. The installation shows Skúli Gunnlaugsson at work. Skúli has crafted almost five hundred light crosses since he retired from farming. He has given the crosses to individuals all around Iceland and some abroad. The photographs show the crosses in their ordinary context all over the country. With the lights he wants to work towards peace, which is the necessary foundation for well-being in the world. Peace has many aspects such as fairness, tolerance and mutual respect. With the peace light it is Skúli ́s hope that we unite in working towards finding new and creative ways to encourage understanding, friendship and co-operation towards the wonders of the world, which we have a duty to protect, and, guided by respect for nature and people, take mutual responsibility for our environment.

Hildur Hákonardóttir’s installation provides us with the opportunity to reflect on the same issues. The work is based on nature and its inherent powers. The world is a place of constant ferment, reflection, coincidence and processes. By directing our energies to the positive, staying still and reflecting we give ourselves the tools we need to exhibit courage, ability and will to give nature the benefit of doubt. „Around 2500 years ago, on the beautiful Greek island of Sicily, lived Empedocius the philosopher. He formulated the theory of the four elements, although the original idea is considered to predate him. The elements were fire, air, water and earth and their companions, dryness, humidity, cold and heat. Humour was a part of Empedocius’s philosophy and presented a simple equation: water+air+earth+ fire=a hare. Religious scholars add one more intangible element: the spirit. I invite viewers to sit down on the tree trunks and contemplate how people concluded that the universe was composed of these four elements in addition to the spirit. Or are we travelling into new worlds in which these powers and their value will change?“ (Hákonardóttir, 2015)

The Relationship between the Present, Past and the Future

Hildur Bjarnadóttir ́s work is often based on women ́s traditional work methods. Her work Giving Back portrays photographs of four pairs of mittens that Hildur knitted for her grandmother in Icelandic wool and hand dyed with colours that Hildur derived from plants her grandmother had planted on her piece of land in Hvalfjörður. „The garden is both a conceptual and material source for this work. I process colours from the plants that my grandmother planted on her land. I look at the plants as a connection to my grandmother as she planted them and cared for them for decades.“ (Bjarnadóttir, 2015) The work ́s title mirrors Hildur ́s giving back to her grandmother who taught her to knit and knitted mittens for her. When her grandmother stopped knitting this tradition was reversed and it was Hildur who knitted and gave her mittens. The work With out title makes references to Hildur ́s origins and her relationship with her grandmother, but the photographs portray the two of them helping each other to knit.

In Clock of centuries Guðrún Tryggvadóttir demonstrates the connections between generations. Communication between generations is the building block for a society of shared responsibilities. This entails allowing each individual to grow into a functional citizen by re-evaluating and honouring the knowledge and values that underpin our feelings towards our environment and our peers. „The Century Clock is a visual presentation of time and an attempt to demonstrate regeneration through direct female descent. The form is a clock; each circle is one century and the individuals of the female line placed in their birth years as far as records reach, or to the year 1685. The closest to us in time is my daughter, born in 1988, followed by myself in 1958 and my mother in 1938 and thus it proceeds further back. On average these equals three generations in a century.“ (Tryggvadóttir, 2015)

Participatory Art

Participatory or relational art departs from relationships between humans and the social context of creating art. The participatory artworks in the exhibition all have in common that they raise the question of who is the author of the work.

In her participatory installation Co-Traveller Gunndís Ýr Finnbogadóttir explores the concept of time. While we imagine that the work ceases to function when we are not present the work lives on in the body of the participant.

The participant ́s experience lives on, both before and after participation in the work. „The bodies of the participants do not only exist in the space (the bus) but also in time and in the journey and in the moment of the encounter with the moments before and after. This provides the opportunity to create a narrative because not all parts of the work are accessible at the same times, such as in a work of sculpture for example.“ (Finnbogadóttir, 2015) In the work Gunndís looks at the participants ́ ideas from the perspective of cultural memory, travel and dialogue. The work builds on the participants ́ journey between Reykjavik and Hveragerði.

The work is the participant ́s experience and in this way Gunndís opposes materialism and at the same time raises questions on museum holdings and the place of artwork that has no material substance in museums.

The book-work Our Nature – My Wishes for the Future shows visualized wishes for future generations created by youth from the South of Iceland under the supervision of Ásthildur B. Jónsdóttir. By inviting people to take part in the project the aim is to foster a sense that art can be a dynamic part of our lives, and to provide a lens through which each and every one of us can examine our perspectives on life. The aim of including this work in the exhibition at the LÁ Art Museum is to create conditions for a dialogue between the young people and museum guests on the exhibition as a whole. This idea is inspired by the philo- sopher Bourriaud who sees artistic practice as a process that always entails making connections between people. The book-work is meant to create a space in which art can fuel our interest in those elements of our society that might be improved, and which improvement might lead to sustainability. With participating in this work, students are given an opportunity to freely express their opinions, allowing each and every one to develop his/her position on issues by listening, reflecting, exploring and assessing arguments. Pre-service art teachers from the Iceland Academy of the arts took part in the workshops.

How can you make a difference? – How can artwork encourage us to approach issues of sustainability from new perspectives? – Is nature making sacrifices for economic growth? – What is the connection between knowledge, place and time? – How can we respond to changes in our environment? – Do we respond rapidly enough to scientific discoveries? – What impact does our lifestyle have on the natural environment? – What do we find natural to buy, renew and destroy? – What sacrifices are we ready to make for our own consumption? – How much “hospitality” do we want to show foreign industrialists when they seek cheap electricity? – Who is Responsible for Sustainability? – What is value? – When are we profiting and when are we loosing? – How can we create a society of solidarity?

Curator:

Ásthildur B. Jónsdóttir (1970) is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Art Education, Iceland Academy of the Arts. She is also a PhD student at the University of Iceland for a joint degree as doctor of art at the University of Lapland Rovaniemi. The subject of her thesis is the potential of contemporary art in education for sustainability. Her research interests include arts and cultural movements that support sustainable development and Education for Sustainability at all levels, within both formal and informal contexts. She has an MA degree from New York University, The Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development and MEd degree from the University of Iceland.

Artists:

Anna Líndal (1957) studied at the Icelandic College of Art and Crafts and completed her postgraduate studies at the Slade School of Fine Art in London in 1990. In 2012 she finished her MA in Artistic Research from St Lucas, University College of Art & Design, Antwerp. Since 1990 she has been active in numerous solo and joint exhibitions in Iceland and abroad, she took part in the Istanbul Biennial in 1997, on life, beauty, translation and other difficulties, curated by Rosa Martinez. The Kwangju Biennial, Man + Space, South Korea in 2000, curated by René Block and the Reykjavik international Art Festival 2005 and 2008. Lindal’s latest solo exhibitions are Mapping the impermanence at the ASI Art Museum and Context Collections / Lines, Harbinger, Reykjavik. Líndal was a Professor in Fine Art at the Iceland Academy of the Arts in 2000 – 2009.

Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir (1955) & Mark Wilson (1954), Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson have been collaborating since 2001. Their work, characteristically rooted in the north, explores issues of history, culture and the environment in relation to the individual and the sense of belonging or detachment. Recent projects use the relationship between humans and selected animals, as a springboard to posit questions on cultural and individual location between ‘domesticity’ and ‘wilderness’. Their work is installation and process based, utilizing photography and video.”

Eggert Pétursson (1956) studied at the Icelandic College of Art and Crafts, 197679 and the Jan van Eyck Academie 197981. His paintings of tiny flowers blanketing his canvases have been charming viewers and confounding critics for years. As Pétursson himself describes these works, they seem to turn mostly on process—the way in which he teases forth the shapes of flowers from the canvas with brushstrokes of color, sometimes barely perceptible under layers of white. As he says of these paintings: “One can easily get lost in the details without ever achieving a complete perception.” Pétursson has exhibited widely and was nominated for the Carnegie Art Award in 2004 and 2006 when he was among prize winners.

The Icelandic Love Corporation is a group of three artists: Sigrún Hrólfsdóttir (b. 1973), Jóní Jónsdóttir (b. 1972) and Eirún Sigurðardóttir (b. 1971). They have worked together since graduating from the Icelandic College of Art and Crafts in 1996 and received recognition both in Iceland and abroad. The ILC uses nearly all possible media, including performance, video, photography, and installation. The works blend humor, subtle social critique and often incorporates ideas of traditional femininity, but they are always women on their own terms. The members of the ILC have lived and studied in New York, Berlin, Copenhagen, and are currently based in Reykjavík.

Gunndís Ýr Finnbogadóttir (1979) received her masters in Fine Art from the Piet Zwart Institute, Rotterdam and Plymouth University, 2008 and her master degree in art education from the Iceland Academy of the Arts, 2011. Her work is permeated by issues concerning with lived spaces, hospitality, acts and rituals of recollection and female identity. Yet her works are neither sociological nor are they nostalgically sentimental, but rather minimal and poetic. She is interested in authorship and collaboration, questioning individuality and the unique. Much of her works are parallel modernistic ideas with our current times.

Guðrún Tryggvadóttir (1958) has a degree in fine arts from the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in München, Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux Arts í París, and the Iceland Academy of the Arts. Guðrún has held several exhibitions, both at home and internationally, founded and run art school, illustrated the children ́s book Mythological Creatures in Icelandic Folktales and in recent years she has managed the environmental website nattura.is, which she founded in 2006. She now works on a series of paintings that visualizes family connections and generational change.

tryggvadottir.com

Auður Hildur Hákonardóttir (1938) studied textile at the Iceland Academy of Arts and Crafts and the Edinburgh Art University. She later qualified as a textile instructor from the Iceland Academy of Arts and Crafts, having taught there between 1969 and 1981 and served as its headmaster between 1975 and 1978, a time of great change for that institutions. Hildur also worked on textiles between 1969 and 1990 and her work was exhibited both locally and internationally. She was active in the SUMartgoup in Iceland and the women ́s rights movement. Hákonardóttir works are found in the collections of the main museums in Iceland and she was awarded the Icelandic Visual Arts medal of Honor in 2010. She is also known as a gardener and a writer.

Hildur Bjarnadóttir (1969) graduated from the textile department of the Iceland Academy of the arts, and with an MFA from the Pratt Institute in New York in 1997 and is now studying for a Ph.D. at the Bergen University of Arts in Norway. Bjarnadóttir has been active and sought after in exhibitions and has participated in numerous group exhibitions and private exhibitions, both locally and internationally. Her work has attracted attention for the originality with which she explores the existence of art and the boundaries between craft and art. Her work can be found in major museums in Iceland, Scandinavia and the USA, as well as in several private collections.

Hrafnkell Sigurðsson (1963) studied at the Icelandic College of Art and Crafts, the Jan van Eyck Academie, Maast richt, and Goldsmith College, London. Sigurðsson’s practice, be it in video, photography or sculpture, incorporates a play with such coentities as nature and culture, the abstract and the figurative, mind and body. Much of Sigurðarson’s work is based on photographic series portraying landscape or its artificial substitute. The immaculate images draw qualities from the tradition of painting, reminding the viewer of the multilayered realities behind the veil of visual surfaces. This feature is furthermore investigated in the artist’s three- dimensional work and videos, where the area between subject and surroundings is explored.

Libia Castro (b. 1970, Spain) and Ólafur Ólafsson (b. 1973) have collaborated and exhibited internationally since 1996. They explore the political, socioeconomic, and personal forces that affect life in the present day. By means of portraying, mapping, intervening and informally collaborating with people they meet, they explore space, the environment and its dynamics in different possible and impossible ways. Their projects have an open ended structure and often result in playful, poetic, subversive and critical works. The artist duo was nominated for the art award Prix de Rome in 2009 and received the third prize. They participated in the European Biennial of Contemporary Art, Manifesta7 and represented Iceland at the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011.

Ólöf Nordal (1961) graduated from the Iceland Academy of Arts and Crafts in 1985 and received a master ́s degree from the Cranbrook Art Academy in Bloomfield Hills and Yale University ́s sculpture department in New Haven in 1993. She also studed at the Gerrit Rietvelt Academy in Amsterdam. Nordal has worked in multiple mediums, but she mostly works on sculpture, photography and video installations as well as public art. In her career she has dramatically explores subjects that connect to culture, origins and folk beliefs while working with local and global issues.

Ósk Vilhjálmsdóttir ( 1962) studied at the Icelandic Academy of Art and Crafts and Hochschule der Künste in Berlin. She works in diverse mediums such as painting, photography, video and installations. Her work stems from her sense of political commitment, often addressing tension between the public and the private and investigating the potential that art holds as a mechanism for dialogue and social change. Her works seek to critically challenge consumerism, globalization, the exploitation of the environment, and the needs of individuals to navigate an increasingly complex daily existence. Vilhjálmsdóttir has received awards for her work and exhibited widely in Iceland and abroad.

Pétur Thomsen (1973) studied art history and archaeology at the Université Paul Valéry Montpellier III, Montpellier; photo graphy at École Supérieure des Métiers Artistiques, Montpellier and at École Nationale Supérieur de la Photographie (ENSP), Arles. He has been nominated for prestigious awards, and has won for instance the international LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy) Young Artists’ Award and in 2005 Pétur was selected by the Musée de l’Elysée in Switzerland to participate in the exhibition ReGeneration, 50 Photographers of Tomorrow. Many of Thomsen’s works show the violent intrusion of mankind into Iceland’s nature. Whether seen as social criticism or as a romantic statement, his work bears witness to the rapid change of Iceland’s land and cityscapes.

Rósa Gísladóttir (1957) graduated from the Icelandic Academy of Arts and Crafts in 1981 and the Munchen Art Academy in 1986. She completed master ́s degrees in environmental art from the Manchester Metropolitan University in the UK and MartEd in art education from the Iceland Academy of the Arts in 2014. Rósa has received numerous awards and her works displayed widely such as at the Mercati di Traiano of the renowned Museo dei Fori Imperiali in Rome, where past exhibitors are international well known artists.

Rúrí (Þuríður Rúrí Fannberg) (1951) studied at the Iceland Academy of Arts and Crafts, as well as metalwork at the Reykjavik Technical College and the De Vrije Academie Psychopolis, in the Hague. She is a conceptual artist and presents her work through different mediums such as sculpture, installations, environmental work, multimedia, performance, bookart, movies, videos, soundart, mixed mediums, as well as computer generated and interactive work. Her artwork has been exhibited internationally, in Europe, the USA and Asia. She represented Iceland at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003 where her work attracted a lot of attention and discussion in an international context.

Spessi (1956) Sigurþór Hallbjörnsson studied photography at De Vrije Akademie, Den Haag, 198990 and Aki Akademie voor Kunst Beeldende, Enschede, the Netherlands, 199394. He has exhibited his photographs in numerous exhibitions at home and abroad. Besides working as an artist, he also handles advertising and portrait photography and is recognised for his unique and innovative approach. His photographs have appeared in major newspapers such as New York Times and Politiken. Spessi has also given photographic lectures at the Iceland Academy and in the School of Photography.

Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir (b. 1985) graduated with Bachelor of Fine Arts from Iceland Academy of the Arts in 2009 and received Masters of Fine Art from Glasgow School of Art in 2013. In her works she considers ideas and definitions of identity, places and the field of systems we use to understand the natural world and how these might be interpreted in more subjective areas through memory and literature. Þorgerður has exhibited her work in Iceland, Scandinavia and the UK as well as heading exhibitions and artists ́ publications in Iceland. She is now the director of the Living Art Museum as well as chairman of the board.

Here you can download the catalogue in Pdf. format.