A World as a Fragment of a Whole

September 28 – December 15, 2019

Curator: Jóhannes Dagsson

The following text accompanies the exhibition The World as a Fragment of a Whole, featuring artists Anna Jóa and Gústav Geir Bollason, at the LÁ Art Museum. In the text I discuss concepts and ideas that informed my approach in curating the exhibition. The works in the exhibition are not about these concepts and ideas; they are autonomous and require no elucidation or illustration. However, by presenting these works together in the exhibition space an opportunity is offered for interpretation and meaning, which in the following writing I will try to outline and elaborate on. The text comprises three parts, each addressing one aspect of the ideas informing the selection of the works and how the exhibition is composed. These are: drawing/time, object and world.

I. Drawing/time

Drawing as a method of making an image of the world is partly grounded in limitations and in establishing limits. Drawing is not only a perspective or a method, but a demarcation. Demarcation can be instrumental in bringing out qualities and phenomena which may otherwise be hard to grasp. To draw is an exploration of certain qualities, an exploration that takes place within the circumstances determined by the tool and the surface. It is our perception and its content that we form and alter by the method of drawing. To make one’s own picture of the world is both a metaphor and a narrative, both a subjective and an objective effort at understanding or experiencing, or sensing.

This kind of drawing is demarcated by the hand of the one doing the drawing (literally and metaphorically), and this quality of drawing results in our interpretation of drawing being partly defined by our ideas about the intentions of the draughtsman, by our ideas about personal qualities (opinions, desires, yearnings, fantasies, etc.) of the one doing the drawing. This applies even when a drawing has a “label” such as map or diagram – concepts that are grounded in ideas such as purpose and objectives. Drawing as a perfect depiction of its subject is thus not possible – or at least it is not an interesting interpretation.¹

Through drawing a new form of access to the world is made possible: the movement of the hands, together with the focus of mind and eye, constitute a method of addressing our perceptions and understanding of the world. Drawing can be thought of as a pattern or rhythm, and time thus becomes a factor in the concept of drawing. Drawing as a pattern in time, drawn, in time. Like a rhythm, or like ripples on a surface.

Time is not of a single nature: it is passing, it is a moment, it is human and eternal; it is geological and it appears in objects that travel with us through the material world. Octavio Paz has argued that when it comes to the image of the world the role of time is especially important: we do not see the world as unconnected moments; rather we understand the world as a phenomenon that has a purpose, as a phenomenon that moves from one moment to another for a reason. This is not only true of human actions (which are, however, probably the most obvious example), but also of how we deal with the world taking on ever-new manifestations, in seconds or centuries.² Time is thus a determining factor in how we attribute meaning to material. For Paz the clearest manifestation of this can be found in poetry, where diverse ideas about time have been expressed with unusual clarity. I want to suggest that drawing is equally apt as access to the world, where this relationship between time and purpose becomes visible. Not in competition with the poetic form, but as another, (possibly) related way to contemplate these connections.

There are many kinds of time in Anna Jóa’s drawings. The delicate fragments carry with them their own time; time that is amorphous and hard to define. They evoke a time when the fragments were part of a whole and not fragments, had no autonomous existence of their own, but were an integral element in a useful object. Since then the sea has played its part in smoothing and shaping them, making the fragments what they are now. The fragments also carry with them different places. The drawings entail references to where the fragments were found, and where the porcelain originated. Natural processes intersect with the manmade – and chance intersects with the circle of nature.

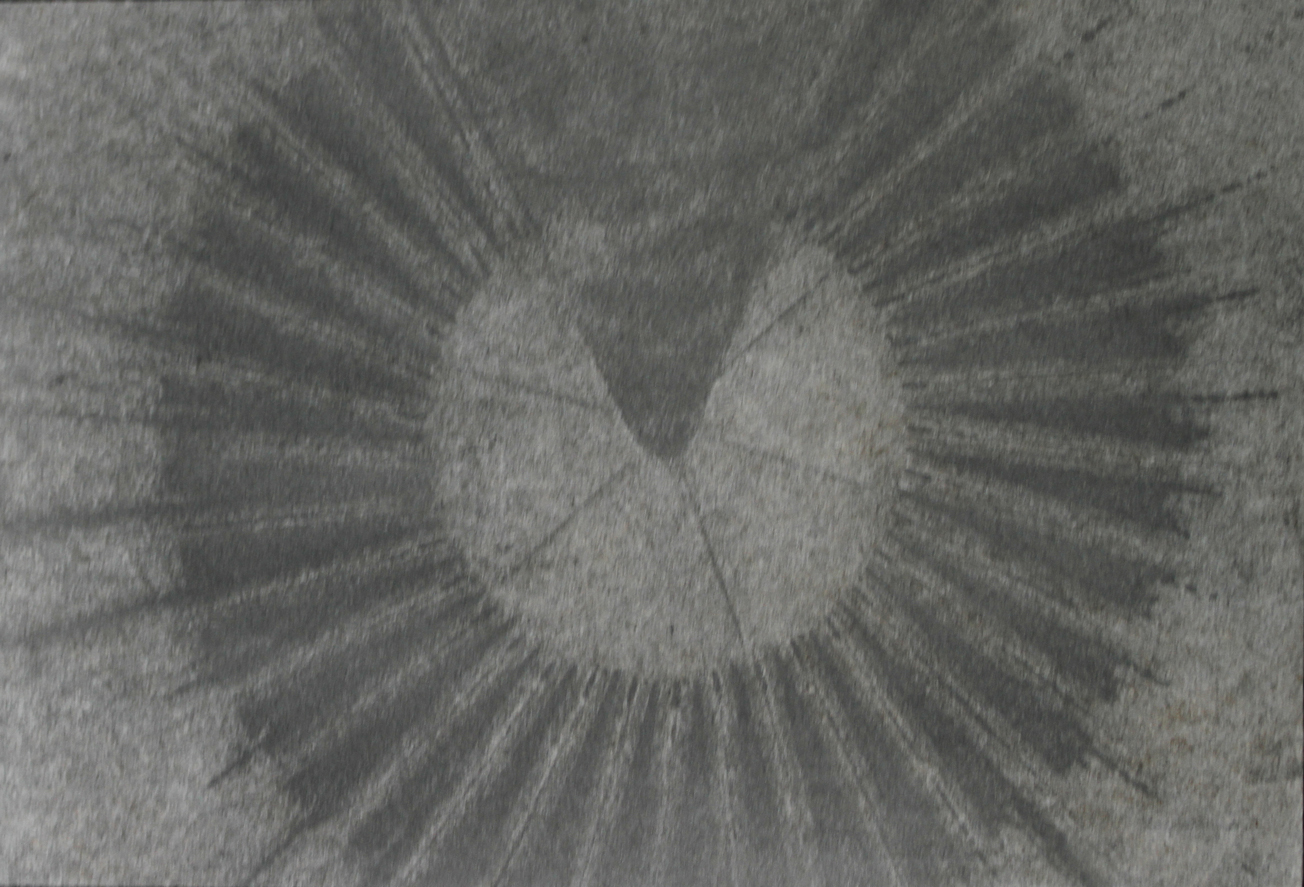

The fragment also carries with it the act of finding. It carries with it a game most people are familiar with – beachcombing, wandering the seashore looking for something interesting washed up by the sea. It is a game played with childlike joy, or with the interest (even concentration) of the adult. The found fragments are like paintings, signifiers, but the natural substances of which they are made want to be reunited with their origins. The fragments, and the shapes on their surface, are found by examining nature; and gradually, nature reclaims them. To find something is a function of placing it within the idea of a thing – but here time, permanence and fleeting meaning are in conflict. Hence time is multi-layered; the fragment stands for the whole of which it was once a part, for nature’s time – smoothed and rounded after its sea journey – and the time of the game, of humanity, of the now. Drawing is a method of analysing these manifold times that lie within the fragment. Pattern, repetition, rhythm – all familiar means of addressing time, addressing the moments, and how best to arrange them so as to form a comprehensible whole. In drawing also, the drawing’s own time is visible. Through the proximity of the artist’s hand, we see a time that is not the fragment’s time as such, but a time that points to the future, to a new interpretation of what the fragment is, what it may mean, what it is that makes it interesting. The documentation is not objective, but demarcated by exploring certain qualities of the fragments. The drawings are individual, each on its own terms, but they are also part of a larger collection, a larger whole. The analysis of the fragments builds up, becoming more and more complex, more and more simple. The collection – collecting and arranging into new wholes – becomes part of the method, part of the analysis. A specific colour, a specific shape, a specific pattern, gives rise to a new distinction, a new demarcation, a new meaning.

We also come across the time of the fragment and of transformation in the work of Gústav Geir, but this is another time, other fragments. The fragments he puts together and takes apart have not been washed ashore: they are parts of a bigger fragment, a fragment of the industrialisation of the resources of the ocean. These fragments are more localised, they belong to the same localised whole. In 1936 or 1937, the young Albert Camus wrote when travelling in Tipasa, Algeria: “In this marriage of ruins and spring, the ruins have become stones again and, losing the polish imposed by man, have reverted to nature.”³ In this fragment Camus draws a distinction between nature and the manmade, between ruins and that which is still in use, between the polished and the rough-hewn. The fragments and ruins in Gústav’s work do not fit within these distinctions. The division between the manmade and that which nature has shaped is not clear; in Gústav’s work the polished is not the opposite of the rough-hewn. It is impossible to revert to nature, because nature no longer exists as a contrast to the manmade – it is no longer a phenomenon that can be invoked in that way. This breakdown of distinction calls for a new ordering, a new classification of reality into comprehensible parts, manageable fragments. Here time plays a major part. The timelines which intersect in the works are not only nature’s time (or spring’s, as Camus put it so poetically), and human time – but also a time of purpose and purposelessness, a time when things have a purpose, and when they have lost it. The present documented by the drawing is a moment from a progression from past to future, a progression which may not necessarily have any purpose, but continues nonetheless. Time as a progression from past to future can only be understood in view of the speed with which it happens. Geological time progresses from past to future, while the processes it is intended to chart take place so slowly that only occasionally are they perceptible to us. In today’s capitalist society we are surrounded by timelines in which time is assessed in monetary terms, processes where the demand for speed and efficiency is overwhelming. This acceleration applies not only to our material existence, but increasingly to the world of thought, perception and feelings.⁴ The future, or our belief in it as an objective, disappears in this ever-increasing speed; we cannot see it for the ever-more-rapid repetitions, ever greater demand for attention, concentration, happiness and fulfilment. Drawing as a method is not by nature an answer to that (and indeed one can hardly say that it is anything by nature), but it may be applied in order to draw up a different speed, another experience of time. An experience that is not contingent upon productivity, or the distinction of the new from what is past; an experience where the moment documented by the drawing is part of a timeline determined by reflection, and an experience whose only objective is to analyse the moment, and then permit it to return to its place in line.

II. Object

Artefacts are objects, and we are in the habit of treating objects as relatively clearly-defined material forms. They are assuredly mysterious in their existence, but generally that is so only in the subjective context of philosophy, art or religion; in everyday life they obey and behave themselves. As a rule we can trust our senses with regard to objects, at any rate. We see (know/perceive) that “that is intended to be a drinking vessel,” and we see that “that is a tool for raking,” and so on. The tool, and the world of the task, is not necessarily obvious to us in all its details, but as a rule we have a sense of where it ends and where it begins. Fragments or ruins are conditions in which the artefact gives way, and transformation takes over from the fairly stable state of the object. That applies not only to the material qualities of the artefact, but also to where we place its meaning, what meaning we attribute to it. One of the factors which undergoes change in this process from object to fragment is the role of purpose or intention in the manner in which we attribute meaning or role to the object. The distinction between artefacts and natural phenomena has often been supported by arguments relating to the concept of intention. If the intentions of the maker of the object determine its form and function, it is an artefact; otherwise it is a natural phenomenon. The distinction may also be stated thus: as long as the object has a purpose and objective it is an artefact; if the purpose and objective are lost it is no longer an artefact, but fragments or ruins or, simply, substance. This distinction, largely grounded in intention, has in the present day become fragmented and fragile, and waits to be superseded. The influence of human actions has spread and become global. It extends to such phenomena as climate – and hence the distinction between the manmade and the natural is dissolving. We are compelled to rethink our ideas about objects and their origins, about how meanings come to be attributed to objects, and how we perceive them.⁵

The idea of an object as a clearly-defined phenomenon in time, with a clear position and clear demarcations; as something which we can see or grasp through our perception of it, no longer applies in circumstances in which human influence is no longer confined to artefacts, but has tainted all the surrounding environment. These new circumstances, i.e. the Anthropocene era, call for new ways to analyse and classify material phenomena – and new ways to think about and reorganise how we distinguish between the manmade and the natural. In the context of the Anthropocene, our relationship with the future is one of the elements affected, which takes on new forms. We influence the future differently from how we influenced it in the past, and this new relationship with the environment of the future demands that we reconsider the meaning we attribute to objects and the distinction between the manmade and the natural. The future will be the work of humanity – although that was nobody’s intention. The future will also be a work of nature, as it will be. We must apply certain measures in order to try to have an impact – whether or not we are responsible. This in turn entails that we must envision the future, not as an objective but as a project which we take part in resolving, before it becomes something of which we can have a direct perception.

Envisioning something as new does not generally require more than the simple act of changing one’s viewpoint, altering one’s position, moving what is being observed into a different context. Some of what we might then see here includes: relationships between object and time, between intention and time, between form and intention, between the moment and time – between the collection as an attempt at documentation, or as a personal response, and the transformation of the object. This list could go on for ever, as every observer has their own version of it.

III. World

What is it that keeps this story together, other than forward motion? A world does not comprise only those material objects that fill it; it also contains the systems and conditions which make meaning possible. A new world can thus contain the same material objects as its predecessor, and yet be new. We awaken into an ever-new world, so long as viable reasons for it exist. The works in the exhibition are not a prophecy about a world, and not a model for the best world in which to live; rather, they are hypotheses or meditations on possible fragments of a possible world. These fragments are worlds and things, on their own terms and self-sufficient, yet also requiring a wholeness and a context in order to survive, to become meanings and actions, to become processes and actions within a world.

Worlds do not come of nothing, and their genesis is not a momentary creation. Worlds come into being gradually and their raw material is other worlds, other units of perception and meaning, which become parts of a new world, and so on, hopefully without end.⁶ One of the challenges of today is precisely to be able to imagine the next world without that world entailing the end of history. “How do you make a world that does not fall apart two days later?”⁷ What does a world need to have in order to be viable? Within literature or arts this is a question of methodology, but it is also a question that can be asked about real worlds.

It is not so simple as that the exhibition is an image of a world, or that the works in the exhibition have been selected with the idea of being a map of a world. The relationship between presentation and a world is far more complex and nuanced than that. The exhibition provides insight into the process of transformation of one world that becomes a draft for the next. Here the analytic examination of the drawing, childlike play, narrative skill, and collection of objects, information, fragments, are all united.

We are provided with access to worlds, a fragmentary route, fragmentary access to worlds whose origins lie both in the past and in the future. The artists’ worlds are different, and inhabited by different beings; but by offering access to them in the same context, conditions and reasons are created for considering such concepts as world, past, future, presentation, viable. Here are indications of worlds which are personal, worlds which contain other actions than those we are accustomed to, worlds which are past, worlds which have yet to begin. The fragments are perceptible, and through our perception of them this access, this fragmentary path, comes to be. These are not worlds made of concepts or subjective specifications or formulae – instead we have an opportunity to experience for ourselves, through perception and existence, a draft of a world.

The outstanding feature of metaphysical poetry of the Baroque age was metaphor, whereby everyday objects become symbols for qualities and laws which are far beyond what we perceive by everyday means. Metaphor in which the essential qualities of the world are reflected in the small and the everyday. Metaphysical meditations which, despite taking place beyond the perceptible, have their origins in our existence in the world of perception.⁸ The exhibition, and the worlds in the exhibition, are not metaphors. But this idea of everyday perception as access to thoughts on the nature and laws of the world is a theme which has stayed with me throughout the preparation of the exhibition.

Ways of rethinking what it is that makes a whole, ways of rethinking what it is that we put together and what we take apart to make new worlds, new possibilities, new patterns to be perceived. New ways to recall the whole from the fragments.

About the artists:

Anna Jóa (1969) is a visual artist, art historian and art critic. She graduated from the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (now Iceland University of the Arts) in 1993 and completed her master’s degree in Fine Arts at the École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs (EnsAD) in Paris in 1996. She later studied art theory and history at the University of Iceland. Her art pertains to memories, perception, places and the relationship between identity and the environment. She has exhibited oil paintings, watercolours, drawings, texts and photographic work, in addition to three-dimensional works and installations. Anna has held many solo shows and participated in group exhibitions in Iceland and abroad. In Iceland her work has been displayed at the Reykjavík Art Museum, National Gallery of Iceland, ASÍ Art Museum and the LÁ Art Museum, and she has also shown her work in France, Finland, Russia, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Estonia and England. Her works are in the collections of public institutions and companies as well as in private collections. Anna ran the Gallerí Skuggi exhibition space in Reykjavík for some years. She has worked as a curator and writer, and taught art history at the Iceland University of the Arts and the University of Iceland. She works as an artist, art historian and art critic. Anna lives in Reykjavík and has a second home in Stokkseyri on the south coast.

Gústav Geir Bollason (b.1966) studied at the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Iceland University of the Arts) 1986-89, studied drawing for a year at Magyar Képzömüveszeti Egyetem in Budapest, Hungary, and graduated with the degree of DNSEP (Diplôme national supérieur d’expression plastique) from the Ecole d’Art de Cergy in France, 1995. Gústav’s work takes on the form of drawings, constructed objects, remaking of found objects, and film. He works equally with abstract presentation, recreation and parallels, and he invents processes where he contrasts different methods and subjects. To some extent he works with the traditional genres of fine arts – generally landscape or landscape narratives. He explores places with a history, traces of human habitation, or collects objects rendered outlandish by nature’s treatment. In the decay one may analyse what they are made of, and in the chaos development may be seen. Gústav’s work has been shown at solo exhibitions, including a major show at Akureyri Art Museum and in France. He has participated in group shows in Iceland and abroad, e.g. in Paris, Munich, New York, San Francisco and St. Petersburg. Gustav lives at Hjalteyri, north Iceland, where he has his studio. He is one of the founders of Verksmiðjan at Hjalteyri, a contemporary arts centre in a former herring factory, which he runs today.

http://www.verksmidjanhjalteyri.com/