At Home

Sigrid Valtingojer

April 8 – June 5, 2017

Aðalheiður Valgeirsdóttir

“… it’s a matter of chance, of course, where one goes when one is young and adventurous, but there is nothing fortuitous about where one stays.”¹

Sigrid Valtingojer

Man has an essential need for a home – for having a place in the world. Sigrid Valtingojer (1935–2013), born in Czechoslovakia, knew for herself what it was to have to leave one’s home country in search of a new one. In 1945, at the end of World War II, she and her family were stripped of their possessions and expelled from the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia, like millions of other Sudeten Germans.² The family moved to Thüringen, then to Jena in East Germany, before fleeing to the west in 1947 to settle in Aschaffenburg am Main.

In an essay, Hugleiðingar við Öskju (Thoughts at the Askja caldera), philosopher Páll Skúlason wrote: “To be an earth-dweller is to sense that one’s life is bound to the earth – perhaps even springs from it – to feel that it is the premise of life itself: I am myself, you are you; and we are ourselves because we seek a place for ourselves. We are – we can be – ourselves only when we are face to face with Mt Askja (or some other comparable signifier of the earth), and can look there again and again, if not in reality, then in our minds.”³

Perhaps it is chance whether we are here, or there; but whether due to chance or destiny Sigrid left Berlin for Iceland in 1961, at the height of the Cold War the same year that the Wall cleft Berlin in two. From that time on, Iceland became her homeland; she put down roots, and it was from here that she looked out upon the world.

Sigrid had qualified fashion and graphic design in Frankfurt and Vienna before she came to Iceland, and she worked as a graphic designer in Reykjavík for some years before enrolling at the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Icelandic Academy of the Arts) in 1975 to study printmaking. She graduated in 1979. Sigrid’s origins at the epicentre of European culture, steeped in German discipline and heritage, set her apart in some ways from Icelandic printmakers and that was evinced in her philosophy and her attitudes to art, and to culture in general.⁴ Her training and work in design also undoubtedly gave her an advantage as she embarked on her career in graphic art, as is apparent in her disciplined methods and her delicate sense of form and colour.

Working with metal and wood

Graphic art predominates in Sigrid Valtingojer’s work. She was one of the leading artists of the heyday of Icelandic printmaking in the 1970s and 80s. She was constantly testing the limits of the medium through tireless experimentation and development, which yielded the most diverse works of art both in terms of approach and technique. She was constantly searching out new ways to pursue her art, and utilised the potential of printmaking to the utmost including the unexpected directions the material may take during the process. She likened her work on a metal plate to a fantastical treasure hunt, where anything can happen.⁵ Different subjects require different media, and Sigrid invariably found her own way to her objective, whether through etching, aquatint, wood- cutting, monoprint or frottage, according to which technique was appropriate. Sigrid enjoyed the craft of printmaking, the gradual evolution of the work on the plate, which requires patience and attention to detail. She might spend a month on a plate before printing on paper. Each step was thus carefully considered, and many test impressions were made before the desired result was achieved. Sigrid established a fully equipped printmaking studio in Reykjavík, and travelled widely both in Iceland and abroad to seek inspiration for her art. She showed her work both in Iceland and abroad, participated in many international shows, and received awards, for instance in Italy and Japan. Works by Sigrid are in collections in Iceland and around the world.

The exhibition Heimkynni /At Home displays some of the varied prints made by Sigrid Valtingojer in 1993–2010.

Landscape – Nature

Sigrid was quick to form a bond with Iceland and Icelandic nature; she was captivated by the landscape, which became an inexhaustible source of inspiration, and the major influence on her art. “When I came to Iceland I sometimes felt that this was what nature had been like, at the time when the world was created. Other countries have woods – and they aren’t like individuals – but every single mountain in Iceland has a personality,”⁶ observed Sigrid.

In landscape she found her creative power in “primeval, untamed, naked nature,” where the basic geometrical forms appear in mountains and other natural phenomena, “open to be read,” as the artist put it in an interview in 1999 in connection with an exhibition at the LÁ Art Museum (Listasafn Árnesinga).⁷ “We are all part of nature, and everything we think we are creating has existed, exists and will exist, in some form. Each individual perceives the world in her/his own way. That perception appears in the artist’s works – because they give the most accurate picture of her/him and her/his perspective on the world,”⁸ she continued.

Icelandic nature and nature-related imagery thus rapidly came to dominate Sigrid’s art. At the start of her career as a graphic artist she made mainly narrative realistic works with surreal overtones. She “read” the landscape and the powerful forms in nature; the light; and untouched nature inspired her to grapple with and capture the essence of creation and perception in the beauty of the land, in her own personal way. The works were, however, not strictly landscapes, as she did not aim to portray a specific place, mountain or region instead applying the forms, colours and textures of the land to express her feelings and subjective bond with nature, which are embodied in her works.

The term landscape refers to “all the visible features of an area of land, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.”⁹ Thus a mountain is not the same as a landscape. The mountain forms part of the landscape from the human perspective, while the landscape owes its existence to the bond between man and nature. Hence we may say that without man there is no landscape, and no landscape without nature.¹⁰ Sigrid observed the shapes in the landscape and the “personalities of the mountains,” as she put it, due to the bond she formed with Icelandic nature and made them her own.

The series Landscape I–XII, made by Sigrid in 1986– 89, is in a sense an ode to Icelandic landscape. In the works she captures the unique beauty and tranquillity of nature in the highland interior, through her deli- cate technical expertise and sensitive use of colour. In each piece she is concerned with certain forms and colours of the landscape, for instance a mountain, glacier or lava field, which she portrays in an abstract sense. She demarcates the forms, delineating clearly- contoured mountains and landscape features, earth forms, vegetation and upheaval. In Landscape VII a volcano is split open, revealing the molten magma within, and in Landscape XI pale-green moss spreads out across the dark-purple rock and black sandy deserts of Iceland’s barren uplands. In 1987 Sigrid won first prize at an international graphic art exhibition in Biella, Italy, for her Landscape V. The shape of the mountain is simplified, its slopes riven with valleys and hollows. Sigrid’s works were deemed to show- case her sophisticated technical skill and her ability to stimulate the observer’s imagination while maintaining a tranquil beauty.

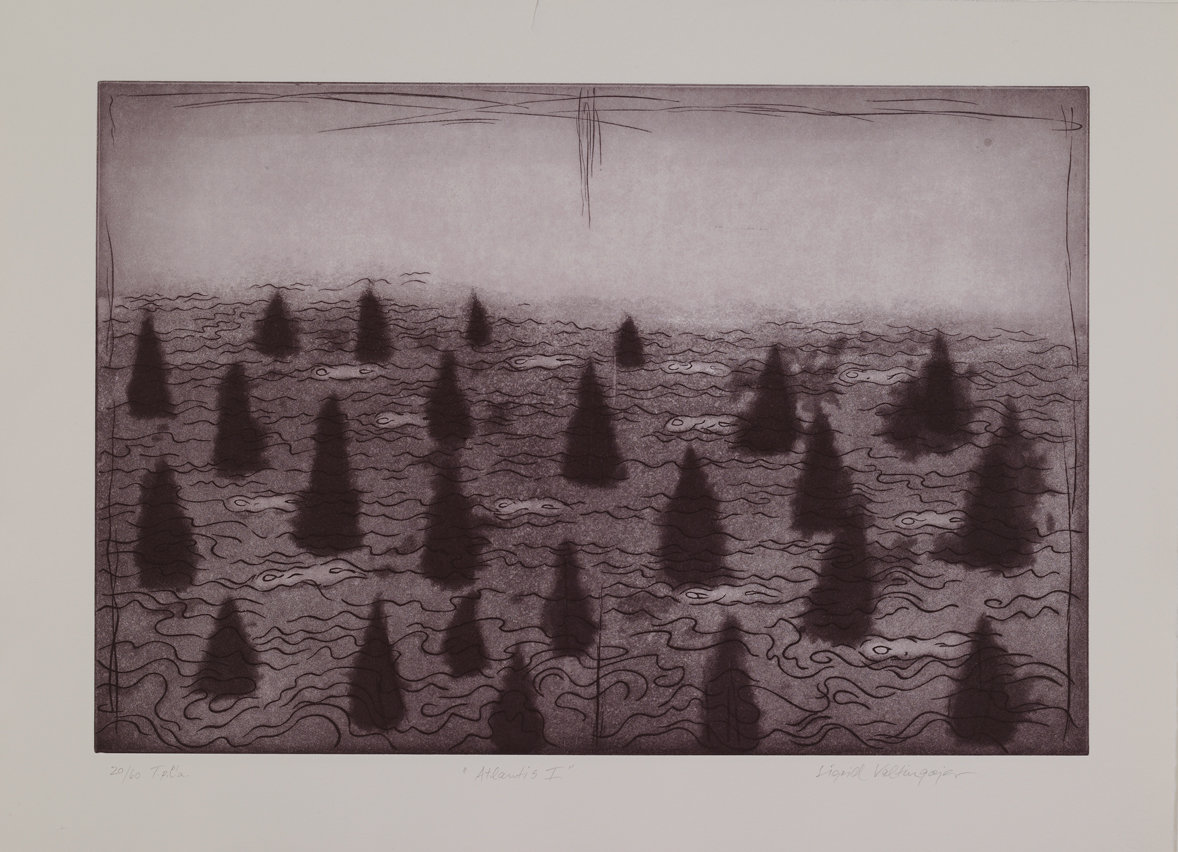

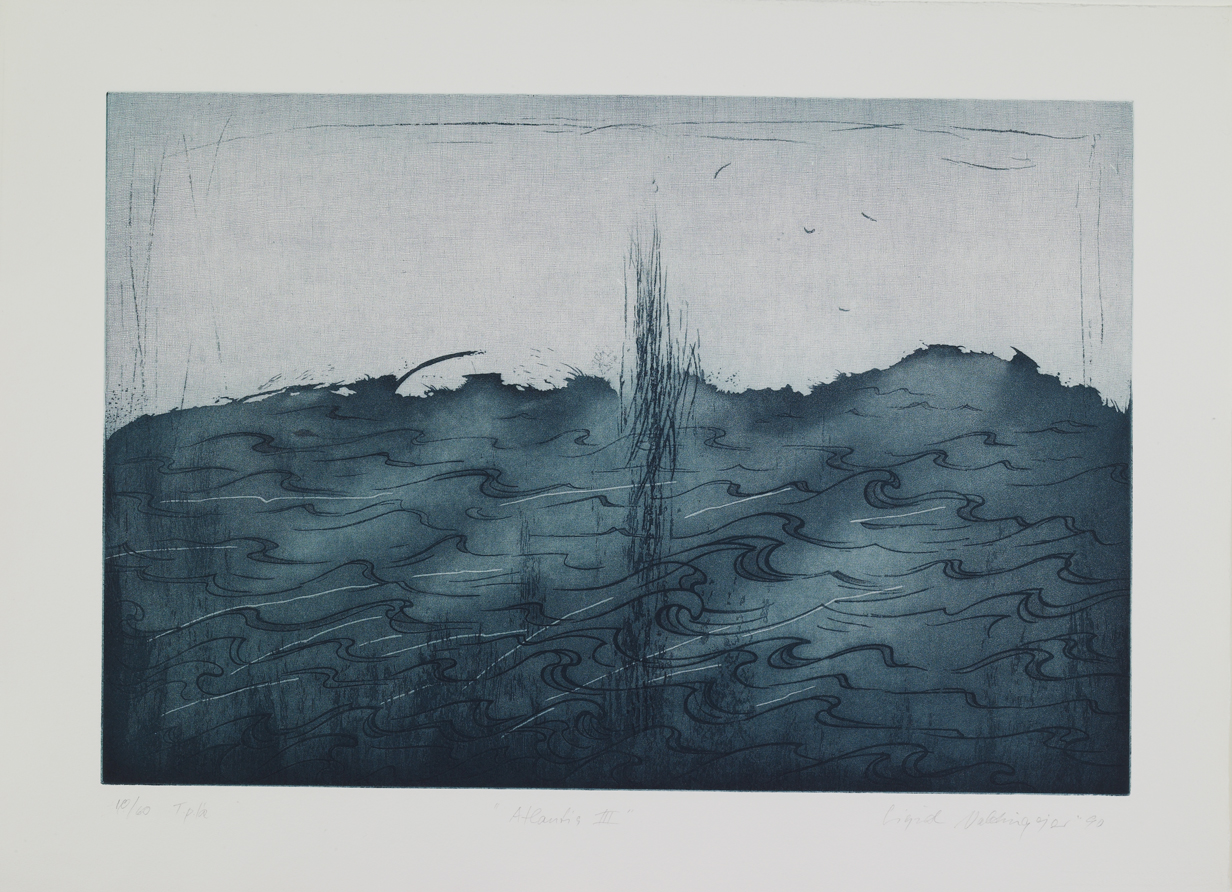

The boundary between land and sea is the subject of Land Possessed I and II (1989). An island rising from the sea in a bluish haze symbolises the beginning and the end in nature’s creative power, which so intrigued Sigrid, and which she depicted in her refined etchings. Creation, wilderness and wide-open spaces of land and sea are Sigrid’s themes in Atlantis I–III (1990): the ambiance of primordial energy and genesis brings the observer closer to the primeval, untamed and naked.

Although landscape provided Sigrid with endless inspiration in colour and form, she started to develop a method which she saw as a way of throwing off the shackles of the forms in the landscape, and making a new start. In 1993 she started to saw and cut sheets of wood and copper into pieces, distributing the forms about the plane in order to achieve new and unexpected juxtapositions.¹¹Thus she made landscape into an expression of her own ideas – although the bond with nature is still evident. At that time she also started to use symbols drawn from Japanese and Chinese characters and ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. Each character or symbol has its own meaning, and by arranging them together with forms and planes

a personal symbolism is created. Two characters from Japanese, for water and mountain, for instance, together signify landscape.¹² Brothers and Sister Meeting Each Other (1992) is a telling example of such works; the artist often used the same forms and symbols in many combinations, thus exploring their different meanings.

Sigrid works on the boundary of the abstract and the figurative in her Theme I and Theme II (1993). The shapes are simplified and disrupted, while the subtle use of colour evokes nature and gives a sense of a wide-open mountain landscape with its slopes and gullies. Thus the artist never loses sight of the land- scape, although unexpected changes may take place in the process of development.

Despite her expertise in etching and aquatint, Sigrid felt a need for greater potential in use of colour, and she found this in the woodcut. Her use of form and colour grew freer, and the interplay of rough and delicate textures more subtle. In Beyond the Plains and Dawn (1997), Sigrid cuts both rough and delicate strokes into the wood, exploiting the grain of the wood to create a vibrant and complex combination of forms and colours.

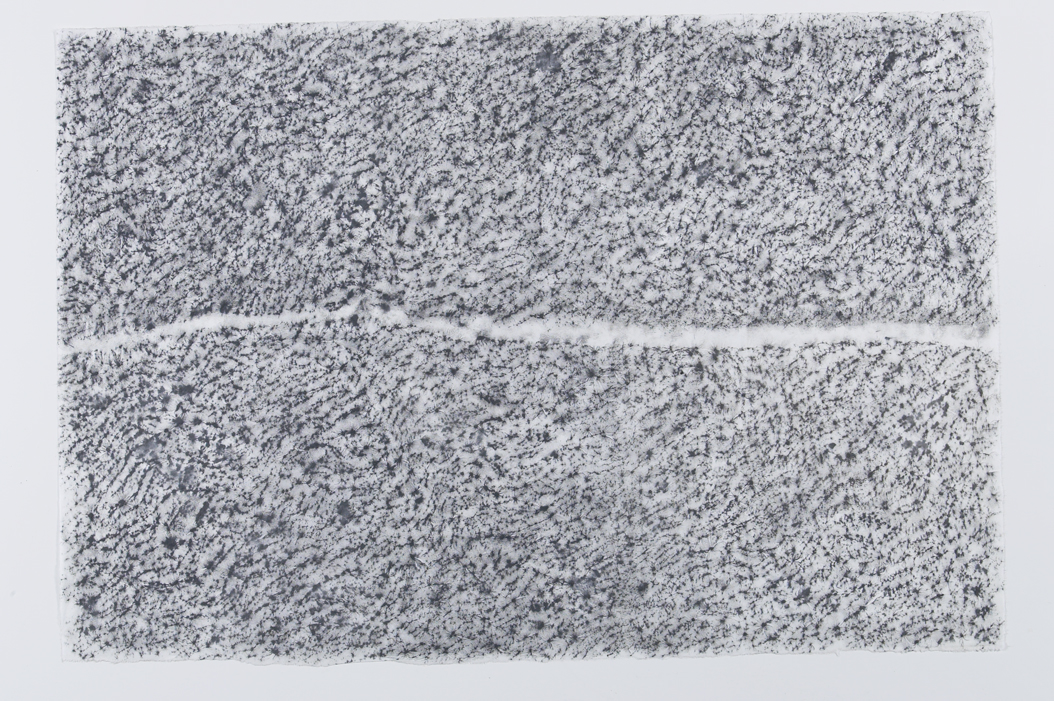

Jóhannes Sveinsson Kjarval, Iceland’s most popular artist of the 20th century, was the first Icelandic artist to discover the magical world of lava, in the 1930s. His paintings of lava fields and moss transformed the Icelanders’ aesthetic perceptions; prior to that time lava fields had been seen as grey and ugly, impassable, and devoid of any quality that might in still a sense of beauty.¹³ Sigrid may be said to have been following in the footsteps of the maestro when she explored the lava surface in the Skin of the Earth series (2003). She learned about the geological his- tory of the lava fields and their age, which she said was a vital factor in making the works. The lava fields she chose for the project were Hellnahraun outside Hafnarfjörður, which flowed in an eruption in 950 AD, and the Þorlákshöfn lava field, which flowed 9,000 years ago. She printed directly from the lava surface on thin Japanese kozo paper, using an age-old Japanese technique. The method is vibrant and subtle, with rough-hewn features depicting the stream of the lava that once flowed across the country, alongside delicate fractal patterns which are seen in all works of nature.¹⁴

Landscape was long Sigrid’s principal subject, but it evolved from pure landscape into simple abstract symbols of landscape, giving her greater freedom to express her own reality. Sigrid’s oeuvre thus varies between free depiction of nature, abstract forms and symbols. Through her unceasing exploration of landscape she embraced certain forms which became a personal symbolic language which she used in expressing her philosophy and the influence she had experienced from nature and the environment.

Symbols and symbolism

Expression and communication are among humanity’s essential needs – whether in words or images. And the boundary between word and images is not always clear-cut.¹⁵ The role of a symbol is to signify something other than itself, something intangible.¹⁶ Thus symbols enable us to express concepts and ideas, with the help of the imagination, while they acquire meaning in the context in which they are placed. Traditional and natural symbols allude to a certain culture and commonality in human existence. In visual art and literature, writers and artists are known to invent their own symbols in order to express and communicate certain ideas and messages. The symbols, however, tend to reference tradition and a specific culture.

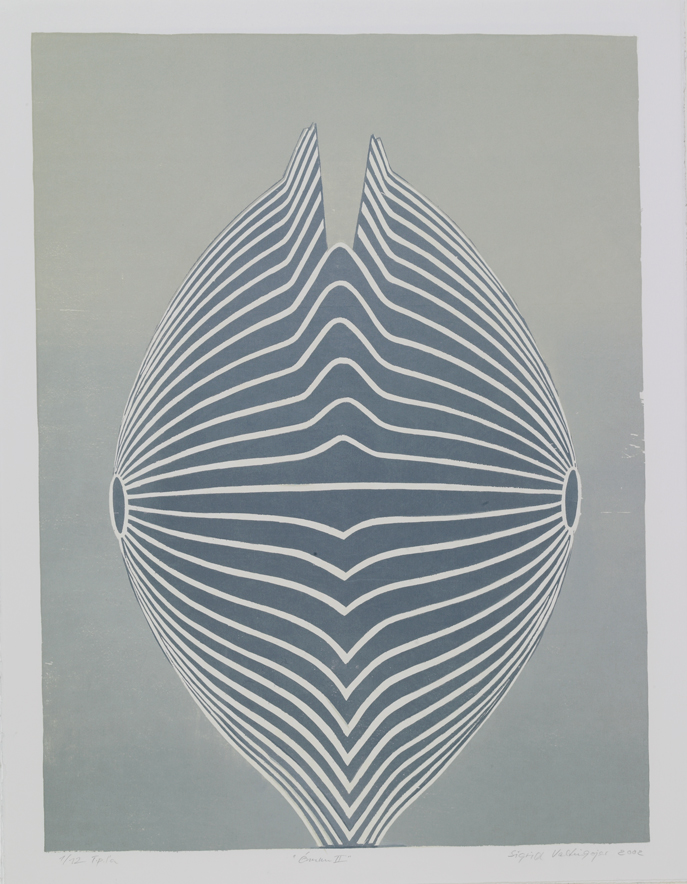

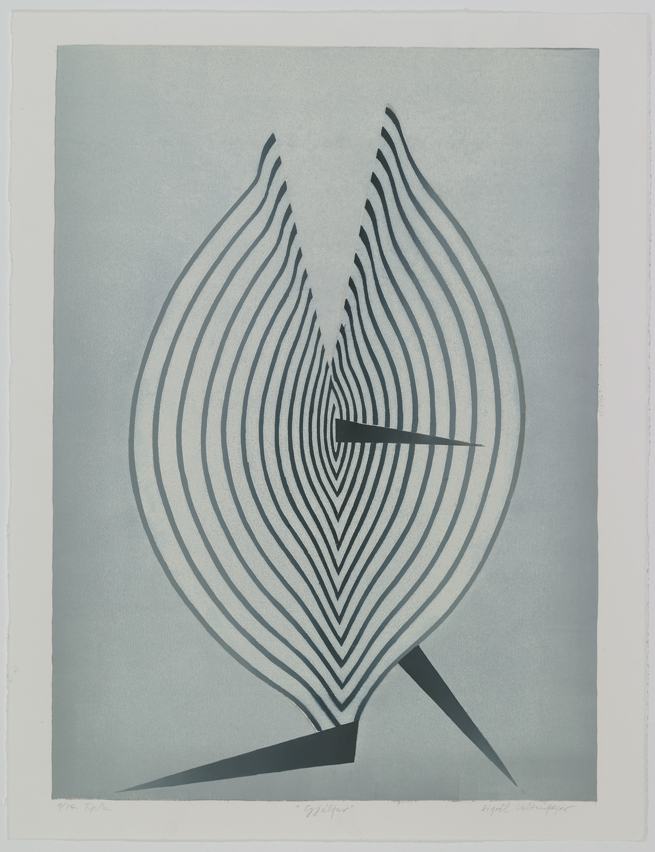

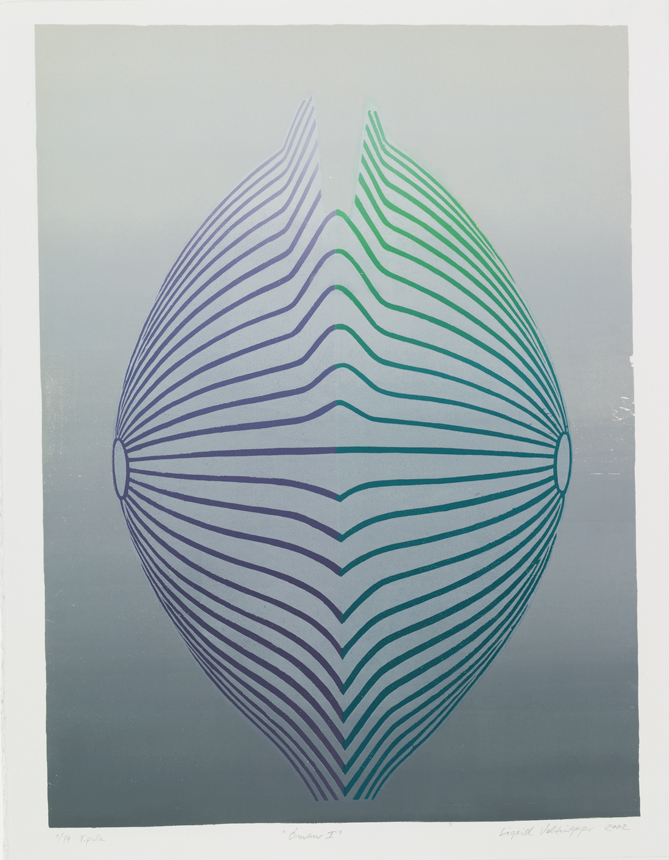

The farther Sigrid distanced herself from direct portrayal of nature in her art, the more abstract the forms in her work as for instance in woodcuts from 2002, in which Sigrid visually depicts sounds and sound waves which originate in man’s perceptions in face of nature. Each work references a specific sound, such as Echo, Lapping, Murmur, Resonance. The works are presented simply and effectively – sound sculptures of a kind, which induce the observer to listen. Vortices, ripples and spirals become symbols in these works, and the symbols have something in common with eastern religions and the symbolism of Indian tantric lore.¹⁷

Sigrid was an idealist with an ardent interest in the outside world and humanity in general. Human freedom, justice and peace were dear to her heart. Sigrid had observed events in Israel and Palestine for many years before she went to Palestine in 2003 as a volunteer with the International Solidarity Movement (ISM). She spent some weeks working in the Occupied Territories, where she saw for herself the impact of the Israeli dividing wall on Palestinians.¹⁸ In her exhibition Voyage with no Return in the Start Art gallery in 2003, Sigrid showed works which were informed by her visit to the “Holy” Land, in a ongoing state of war. In her etchings she works with the names of cities in Israel and Palestine, using characters of her own invention, grounded in the feelings she experienced in the cities she visited. Behind the city names are symbols which lend the etchings an aesthetic overtone, in addition to the serious political content. The title references the effect of the journey on her – a journey from which returned a changed person.

Sigrid was concerned about the situation of refugees – being familiar with the insecurity with which they live. In 2010 she held an exhibition, Silent Steps, at the ASÍ Art Museum, highlighting the fate of the millions of refugees who have sought refuge in Europe. In these political works she addressed one of the major problems facing the world today. In an interview relating to the exhibition Sigrid said: ”I travel abroad a lot, and in some cities there are whole quarters where immigrants live, in hope of a better life than they had in their home country. Those journeys have enriched my life, and the impact they have had on me is now bearing fruit in my works.”¹⁹ By using letters and symbols from her own world view, Sigrid evokes the experience of refugees who have to adopt a new language and culture as they settle into a new home – which can give rise to problems, but also be a source of new opportunities.

Sigrid Valtingojer’s art addresses many aspects of human existence. Her works manifest her view of nature, the bond with the earth, and the importance of having a place in the world. In her refined works she conveys many fundamental aspects of existence in a symbolic manner – and what it means to be a human being in the world. She chose Iceland as her “place in the world,” as the tranquillity and unspoilt nature, far from the world’s conflicts, became her sanctuary. She could look out from her refuge, “both in reality and in the mind.”²⁰

Asked what it had been like for her to be an artist in Iceland, Sigrid replied: ”It has given me everything. Had I not come here, I would have become a completely different artist, and I would have been doing quite different things from what I have done. Going out into Icelandic nature, or simply observing it, is in my mind an inexhaustible source. You go out, and come home again having been impressed by something, or had an idea.”²¹

Curator:

Aðalheiður Valgeirsdóttir (b. 1958) is an artist and freelance art historian and curator. She graduated in 1982 from the graphics department of the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Iceland Academy of the Arts). In 2011 she graduated from the University of Iceland with her BA in art history with a minor in cultural studies, followed by an MA in the same field in 2014. At the start of her artistic career Aðalheiður focussed on printmaking, later turning to painting as well as drawings and watercolours. She has held over twenty solo exhibitions and participated in many group shows around the world. Lately she has also worked as a curator, and last year she and Aldís Arnardottir were co-curators of Layers of Time – Karl Kvaran and Erla Thorarinsdóttir here at the L.Á. Art Museum.

Artist:

Sigrid Valtingojer (1935-2013) was born in Teplitz, then in Czechoslovakia, and she lived in Germany 1945-61. She studied at the Institute für modegrafik in Frankfurt am Main 1954-58. She moved to Iceland in 1961, and worked for some years in advertising design. In 1979 she graduated from the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Iceland Academy of the Arts), and she taught in the graphic arts department of the college 1986-2001. She was a visiting tutor/artist at the Kyoto Seika University in Japan in 1990, and pursued further study at the Winchester School of Art in Barcelona 2001-02. Sigrid held many one-woman shows in Iceland and abroad, and her work is in leading collections in Iceland and around the world. Among the awards she received was the Grand Prix at an international graphic art exhibition in 1987 in Biella, Italy. The causes of the environment and peace were important to her. She campaigned for Palestinian rights, and in 2003 she travelled to Palestine as a volunteer. She held shows in support of the cause in Iceland and Germany.