Considerable

Brynhildur Þorgeirsdóttir

Guðrún Tryggvadóttir

23. September – 17. December 2017

Heiðar Kári Rannversson

independent researcher and curator

In the exhibition Considerable, Brynhildur Þorgeirsdóttir and Guðrún Tryggvadóttir at the LÁ Art Museum, the focus is on the extensive artistic careers of Guðrún Tryggvadóttir and Brynhildur Þorgeirsdóttir, which span nearly four decades. The show brings works made in recent years together with others from Guðrún and Brynhildur‘s early years in art: each held her first solo show in the early 1980s. The exhibition provides an insight into the evolution of the two artists‘ works, while also demonstrating that their art has reflected a consistent visual world from the outset.

The exhibition comprises two separate but connected elements. The artists‘ older works, displayed in the Gallery 4, express the Zeitgeist of the 1980s, where form and content manifest attitudes opposed to the conventional art of the time. The ideology behind Guðrún and Brynhildur‘s work at the time has links to the slogan of Punk: Do It Yourself. But unlike Punk, which has long been a slave to fashion, Guðrún and Brynhildur have always been consistent. The observer sees this when standing before the more recent works in the two largest galleries, as well as in the foyer and in front of the Museum building. These show how the artists‘ attitudes to life and art have enabled them to create a very personal oeuvre, unlike anything else in Iceland.

Brynhildur and Guðrún both have personal ties to the county of Árnessýsla. Brynhildur was born and brought up on the farm of Hrafnkelsstaðir, while Guðrún has family roots in the county and has lived for some time in Hveragerði and the Ölfus district. But that is not all they have in common: both studied in the 1970s at the College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Iceland Academy of the Arts), then continued their studies abroad. Guðrún studied at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts in Paris and the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, graduating in painting and printmaking in 1983, when she was awarded the Debütanten prize as the best of her graduating class. Brynhildur studied at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam and later at the National School of Glass in Örrefors, Sweden. She then crossed the Atlantic to pursue further study at the California College of Arts and Crafts and the Pilchuck Glass School in Washing ton State. After completing her studies in 1982, Brynhildur spent some years in Iceland before going back to the USA, where she lived in New York until 1990. Guðrún too returned to Iceland after graduation, and after a year in Berlin she also went to the USA, to Cleveland, where she lived until 1992. She lived in Iceland for a year, then moved to Germany. At the beginning of this century Guðrún returned to live in Iceland.

An indistinct memory of attitude

The first time that Guðrún‘s and Brynhildur‘s work was seen together was at the outset of their careers, in the exhibition Gullströndin andar/Breath of the Gold Coast in Reykjavík early in 1983. The show was held in the Jötunn building, where they and other artists had studio space; the building had been leased the previous year on Brynhildur‘s initiative, while Guðrún lived and worked there for one winter. That landmark exhibition presented the leading ideas of contemporary artists in the early 1980s: the formal character and means of painting and sculpture were radically deconstructed by a new generation of artists. With this show Guðrún and Brynhildur may be said to have introduced into Iceland new trends in art: they had both recently completed many years of study abroad, and they were both responsible, along with other artists, for the organisation and installation of the show. But they may also be said to have set off from the Gold Coast on a journey to explore new lands – as both went abroad again, and remained there throughout the 80s and into the 90s, practising their art.

The first time I saw Guðrún‘s and Brynhildur‘s art was many years later, and separately. I had first become acquainted with their work through photographs in catalogues – as I was only a few months old when they first showed their work together. The Gold Coast is an exotic place veiled a mystical aura. The idea of the pictures sparks an indistinct memory of “attitude,” that persists long after the works have vanished from view.

Woman on a rock

The work by Guðrún Tryggvadóttir that I first remember seeing is not a painting – which has been her preferred medium for a long time but a photograph. I recall a black and white portrait of a woman on a rock. She displays her naked body among rocks on the seashore, her upper body twisted so that her face is turned away from the camera. The image should more accurately be called a “pose,” as the form of her entire body is the subject. A photograph can equally well be a frame from a film; and I remember imagining that in a moment the woman would start to move, shove at the rocks or climb over them. There is attitude in the work – in the sense of the artist’s posture in the photo graph, the physical expression entailed by the curve of the body.

A step in an expressionistic dance. But the word attitude may also be taken to refer to the attitude to the photograph itself, that makes the artist’s body the subject and theme of art. In the work the observer is able to see the artist in closeup – quite literally – and that is precisely a characteristic feature of Guðrún’s art as manifested in other works in this exhibition. Another attribute of her art is also seen here: her delicate sensibility for tension and composition in the picture plane.

I later learned that the photograph had been taken by the Hudson River in Inwood Hill Park in New York, where Guðrún spent the summer of 1982. It was published in a catalogue accompanying her degree show at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich the following year. It is part of a larger work in which the artist used Inwood Hill as the setting for installations and performance art: among other things she painted on rocks along the shore and on newspapers, some of which were displayed like paintings. The photograph is thus a standalone work, while also being a documentation of a performance and an ephemeral installation.

Among the older works in the exhibition, fragments of Guðrún’s multilayered work are seen: the works, in the collection of the National Gallery of Iceland, use newspapers as the material plane of the painting, while the content of the newspaper also becomes a part of the subject. Two older photographic works are also seen in which the artist’s body is the subject. In one the artist has been “standardised” and divided up according to internationally recognised DIN norms (Deutsche Industrie Normen) – which apply, for instance, to paper sizes. Birthmarks on Guðrún’s body are assigned an undefined significance in the work, which is a minute examination of the artist, while also being a trenchant critique of the systems which seek to circumscribe us. In DESTRUCTION, from Guðrún’s first solo show in Iceland, the artist has cut that word into her arm and photographed it – one letter per day. The photographs show how the cuts which inscribe the word on her body heal and fade as the work progresses, thus erasing the meaning of the word destruction. Destruction is also its opposite, creation – in this case seen as the organic process of the healing skin.

More recent works by Guðrún in the exhibition also address ideas about organic processes – whether in a person or in nature, and the possible links between them. Large series of paintings by the artist made in recent years convey the artist’s complex ideas about what may be called lifespan; the series Bloodline, for instance, focusses on her relationship with her foremothers. Here the observer senses the progress of time not only in the subject and import of the works, but also in how the painting has been made on the canvas. This becomes clear in the artist’s latest works, which are close to abstract expressionism. The works, Fourth Dimension, The Foundation of Everything and All is the Same, are of huge size and power fully painted, so that the artist’s physical exertion in making the painting becomes almost tangible. Her movements can be traced across the space of the canvas. As seen in the most recent part of the exhibition, Guðrún applies different techniques in every picture as each new idea calls for a new method, in the artist’s view. Overall, however, a consistency emerges between chaos and balance a view of art as an ongoing life or death process.

Pair

The first work I remember seeing by Brynhildur Þorgeirsdóttir is also photographic – not a photo graphic work as such, as in Guðrún’s case, but an unconventional documentation of art. I recall a black and white image of a pair of figures leaning against a wall in an unspecified space. The pair are the same, yet not. One of the bodies is a man, the other a sculpture. It is as if they have leant against the wall to pose for the photographer, and I remember having imagined that they would then go on through the tunnel, up to the surface and out into the street. The photo shows how the curve of the man’s body follows the shape of the sculpture – or is it the sculpture which is modelled on the man’s stance? It is unclear whether this is an original or a copy. But clearly there is a relationship between the pair. The sculpture could even be called a portrait. There is attitude in the work – in the sense of the posture of the subject, the tension between the man’s physical expression and the form of the sculpture. “Punk” staging. But attitude may also be taken to mean an attitude to the surroundings where the photo is taken – art in the direct context of the space – which is one of the characteristic features of this artist, who has made many works in public spaces. Another feature of Brynhildur’s work is also seen here – audacious formal approaches, with precise spatial development.

The implication of the title of the work in the photograph, Axel, is that it portrays one of Brynhildur’s close friends, Axel Hallkell Jóhannesson. It is a mixed media work using plywood, foam, sand, varnish, glass, silicon, whale baleen and horsehair. I first saw the picture in a catalogue for an exhibition by the artist at Kjarvalsstaðir – Reykjavík Art Museum in 1990. It was taken in a nearby pedestrian under pass under the Miklabraut main road, in 1983, the year of her first solo show in Iceland. Sadly, I have discovered that the work is long lost.

The older part of the show includes works made at around the same time as Axel. Two sculptures of concrete, glass and steel – untitled works from Brynhildur’s first solo show in Iceland, now in the Living Art Museum collection – are of the same nature. They may be seen as a pair. In this case it is unclear whether they are images of someone, although they have human attributes: legs, torso and hair. But another two works of a similar time may be seen as prototypes of man and woman – the first couple, in the Christian context. But it is perhaps unlikely that the artist turned to the Bible when making her Typpið og Píkan (the Prick and the Pussy). The two organs are portrayed as roughly formed vertical and horizontal forms – whimsical portraits that also address the concept of creation, whether artistic or biological.

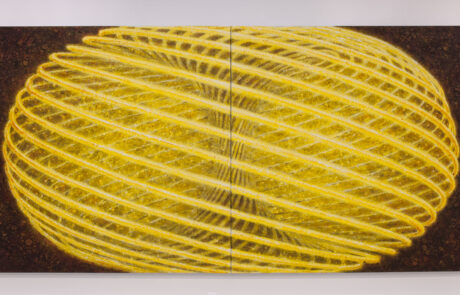

More recent works by Brynhildur in the exhibition show how the artist has continued to work with portraits and pairs as her subjects. Here the observer sees a series of basreliefs on a wall: enigmatic works which are nonetheless powerful in character, they may be seen as a contemplation of the portrait form per se – and indeed the title is, simply, Portraits. As in Brynhildur’s previous work, they are not images of a person or an animal, but of beings that spring from the artist’s experience in the material and formal development of the work. Here we see how Brynhildur directly addresses the space of the museum: the first work that greets visitors to the exhibition is a huge mountain outside the main entrance of the LÁ Art Museum, a mountain which has been named Árnesingur – or “Árnessýsla resident.” The work, while leading the observer into the museum, and interacting with the public space of the town of Hveragerði outside, has connections with other, smaller works in the shape of mountains in the gallery itself. Overall, it is not least the space between the objects which matters: an attitude to art as an ongoing dialogue with form and matter.

Latitude – Attitude

A visitor who stands before the works of Brynhildur Þorgeirsdóttir and Guðrún Tryggvadóttir in the exhibition Considerable at the LÁ Art Museum will observe that from the outset the two artists have been consistent in their art. As implied by the title of the exhibition, and as discussed above, each has had a considerable career, in many senses. Not only has each produced a considerable oeuvre; many of their works are also considerable in scope, as we see in the exhibition. Their works are readily identifiable and personal in nature. Here we see creatures and beings on the borderline between figurative and abstract that emerge from the artists‘ unique visual worlds – as well as their sense of self. During their careers Guðrún and Brynhildur have never done as they were told. It is this attitude – to adopt a stance and an attitude – that makes their art well worthy of consideration.

Brynhildur Þorgeirsdóttir

B. 1955. Brynhildur studied at the Iceland College of Art and Crafts 197479, Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam 197980, Orrefors Glass School, Sweden 1980, California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, USA, 1980-82 and Pilchuck Glass School, Stanwood, Washington, USA 1992, 1998 and 1999.

From the start of her career she has been a leading Icelandic sculptor and chaired the Reykjavík Sculp tors’ Society 1992-95.

Her main materials have been concrete and glass, which she has worked in using new techniques, and recently she has focussed her attention on beings and creatures, mountains and landscapes. She has exhibited widely, in Europe, Japan and the USA, received various awards and had indoor and outdoor works set up in public spaces both in Iceland and abroad.

Guðrún Tryggvadóttir

B.1958. Guðrún studied art at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich 197983, École Nation ale Supérieure des BeauxArts in Paris 1978-79, and the Iceland College of Arts and Crafts 1974-78.

She has held many exhibitions in Iceland, Europe and the USA, and received many awards, both for her art and for her work in innovation; she has been a pioneer in various fields, founding and running an art school and creative design studio, which she ran for years in Germany and Iceland. Guðrún also launched the environmental website nature.is, which she managed for about ten years; she has played a leading role in environmental education since her return to Iceland in 2000.

Today Guðrún works mainly in oils on canvas: her paintings have an ideological basis and are very personal, with the focus on giving visual form to time and matter, and the relationship between generations and the universe. Works by Guðrún are in public collections in Iceland and other countries.

https://tryggvadottir.com/en/