CONTAINERS

Sirra Sigrún Sigurðardóttir

May 16 – July 12, 2015

Curator: Inga Jónsdóttir

How does art stir the viewer ́s imagination? How can art provide us with a different view on existence, raise awareness, stimulate discovery, which is no less important than other learning? What enchants the artist ́s creativity? Is it something in the environment and if so, then what in the surroundings?

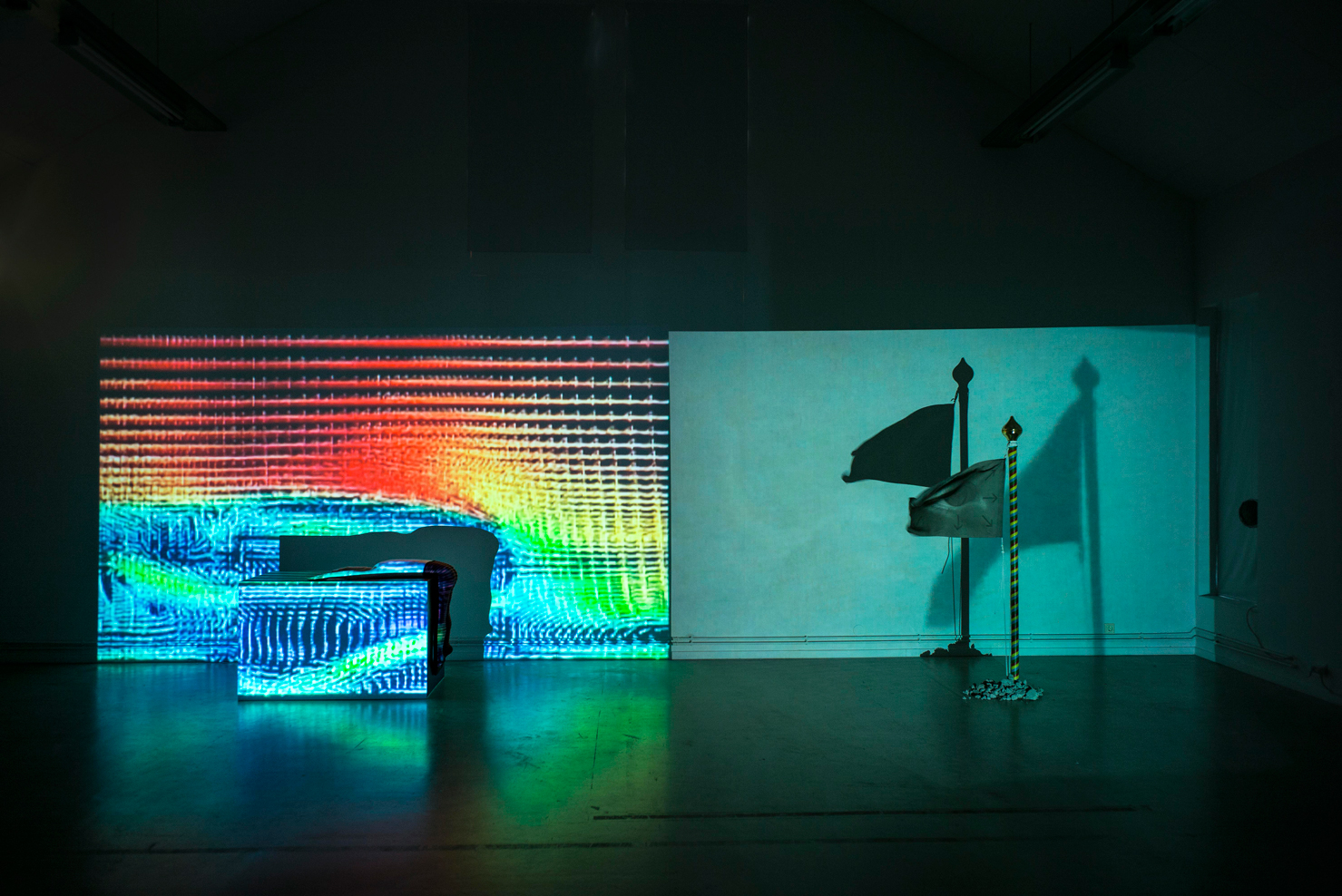

Looking at the art of Sirra Sigrún Sigurðardóttir awakes such questions. With a great deal of deliberation she considers a variety of subjects relating to human existence, upon which her art is based. Systematically Sirra works with statistical information, graphical results of scientific research or theories, transforms them and adapts them to the principles of art, such as colour, form, space and time. In her installations she creates illusions that carry the viewer to sense experience, sometimes with reference to art history, either personally or in a broader context, mixed with humour and seriousness.

In the exhibition CONTAINERS guests are invited to enter the imagery-world of Sirra and view both new and older works, most of which have not been previously exhibited in Iceland. In December 2012 Sirra was selected by the art magazine Modern Painters, as one of 24 international artists worth following in the coming years. Therefore, and with enjoyment her art is now presented in LÁ Art Museum where one can see how even the local community is included in her work. Sirra was born and raised in the nearby town of Selfoss. The exhibition is part of the 29th Reykjavík Arts Festival 2015.

“The source can come from anywhere …”

Guðni Tómasson art historian

Sirra and I meet up in Kling and Bang gallery in downtown Reykjavik on a cold and sunny April day. Sunlight flows into the white painted space, which is partly darkened. Sirra has been among the artists here responsible for the gallery ever since it was founded in 2003. With her collaborators she has exhibited the works of many contemporary artists. Our meeting takes place in between exhibitions but the works of American artist Carolee Schneemann are still in the gallery.

Guðni Tómasson:

When looking at your works, Sirra, one often sees glimpses of some sort of scientific material that you use in your own way, or even a scientific approach that mixes with the aesthetics of the works. Is there a scientist somewhere deep down within you trying to break free or what are the benefits of such practices?

Sirra Sigrún Sigurðardóttir:

I think my interest in science goes back to my childhood, not that I was constantly doing experiments or anything like that. My favourite books were encyclopedias with explanatory photos or diagrams. The text was less relevant to me, while these diagrams caught my interest. I think their aesthetics were hugely important for my visual development. In many fields of science and research illustrations are of key importance in reaching an understanding of the subject. This connection between scientific texts and illustrations is something that I have looked into later on in life. This interest in the graphic representation of science goes back a long time, but I don’t think there is an undiscovered scientist or anything like that in me. While working with this sort of material you are constantly learning something new and fascinating.

I always feel that I have to read and develop a certain foundation and understanding, even though the trigger is usually just a diagram from some scientific field.

G.T.

Of course we use pictures to understand the world we live in.

S.S.S.

Yes, the fields of science and visual arts are related and have to a large extent come closer together in the last few decades or so, for example in the fields of health and space exploration, the best example is maybe the contribution of the Hubble telescope. I was a relatively late reader so illustrations were important to my understanding, which may be true about most children. In this respect you travel in circles and I am revisiting the diagrams and using them as my material. But it is not important to me whether this material comes from “correct” sciences, from some sort of pseudo-science or out-dated ideas. The source can come from anywhere. The visuals have to be interesting and able to catch my attention.

Some of my works are diagrams where the text has been erased and only clean and colourful illustrations remain for example. The first such large work that I did is really a diagram dealing with the historical development of life on earth for 10 thousand million years (2008) and this work was exhibited in the group exhibition Acknowledging knowledge in LÁ Art Museum in 2010. In it I removed all the textual information but some sort of information was nonetheless still there, although this was harder to decipher and the work became more abstract. The aura of science somehow remained while the image was also connected to art history by this transformation. Other such works, borrowed from the world of science, in fact become landscapes.

G.T.

Yes, exactly. In your latest works in this exhibition, a series called Occlusion (2015), this happens. Some of these photos are borrowed from within the eye, correct?

S.S.S.

Yes. These are photos of blockages in the veins in the eyes and also other medical conditions that cause blindness. I came across these photos and for me they are landscapes, so I am really illustrating, rather directly, how blind we are when it comes to the nature that surrounds us. For me it is important that these are photos from within the eye as our sight is not just what we see, but also what we do with the information that we receive. I just feel that we are really numb when it comes to our interaction with nature.

G.T.

There are also those that look at nature through the lens of art. Of course visual art shapes how we view nature, or are we seeing that becoming less and less important?

S.S.S.

Yes, that is also relevant, but maybe this is diminishing in the case of younger generations. I always feel that older generations had more of a connection to visual art and this formed their ideas about the land and the nation a lot more than it does today. People knew the “big names” in art. The landscape painters created icons and landscape became a part of the ideology behind the claims of independence. It is interesting that we looked towards the middle, towards the wilderness and to the mountains, rather than out to sea. Thankfully I was dragged all over the country as a child and nature somehow filtered in, rather than the editions of the painters; I experienced them later. So what you get is some sort of mix of real nature and mediated versions of it.

G.T.

But in regards to science, we now live in extremely educated western societies where science nonetheless is often disputed despite being properly tested and proven. The position of science is even sometimes under threat.

S.S.S.

Yes. This is exactly what is so interesting about our times, how easy it is to misuse information to support a certain case or certain forces. I can change what I want from the world of science and of course anyone can fix information for the cause they are supporting, knowingly or unknowingly, but it is what lies behind this misuse that is important. Whether we are talking about politics, economics, global warming or something else it is very important how information is put forward in speech or text and also in illustrations. You can easily change how high your curves are or where your lines start leaning and so on. We live in an age where we are drowning in information and it can be hard to figure out what is right, what has a strong foundation and what doesn’t.

G.T.

But you don’t really put forward a certain theory before you start to work on another work of art – are you really that scientifically minded?

S.S.S.

No, no. What is so interesting about art is that it does not require a certain conclusion, unlike what happens in science in general. But it is often the case that scientists can be studying something for years without a definite result or a given practical use for the studies. So a lot of things in the world of science revolve around really abstract ideas and what often seem to be surreal theories that are put to the test. In art you can say that the artist offers to the viewer what you might see as an equation that has to be worked out somehow. The viewer can try to come to terms with it, to deem it proven or unproven in his own mind. We each experience art with our own knowledge, history, experience and emotions. I never know what “the other” will see or add to the equation. This is what makes it interesting to borrow scientific visual material because while someone encounters something abstract in these works, the next person finds information, even though I will have erased it already. It is hard to talk about a conclusion in the field of art that I consider myself to work within. A work of art can mean something totally different in 10 or 50 years than it does today, so the “time” of the works is very unclear and also where it begins and where it ends. The process and the slow flowing message of the work become independent. Even though you are working for a certain exhibition there is nothing that says that it cannot go on evolving. Certain objects and symbols flow between my works. These make the works a slightly more difficult commodity, while a larger contextual conversation takes place.

G.T.

I get the feeling that this isn’t that unlike someone that puts forward a theory and has to put it to test, even though the experiment or study takes time.

S.S.S.

I find it extremely charming, and this is very understandable to an artist, that people dedicate themselves to certain tasks, even for years, without a definable conclusion. The path and the search is what I find fascinating. This is why I think the scientist and the artist often have many things in common in the way they work. In both cases this is a study and an observation of the world, life and society. For example I find it very fascinating to read the biographies of scientists, even more so than the biographies of artists. There is often a tremendous persistence there that I find charming.

G.T.

Like in many works of visual art and in fact in most fields of art in Iceland the economic crash of 2008 and onward has been projected. You searched for aesthetic material (in the work Landmarks) in the Report of the Special Investigation Commission of 2010 that was presented to The Icelandic Parliament (Alþingi). You took certain graphs from the report and paired them with iconic Icelandic landscape. How did this come about?

S.S.S.

Well, in fact I just stumbled upon this. It is a good example of this strong Icelandic vein of landscape art. I was living in New York and like many of my countrymen I was browsing through this huge report in pdf files. While scrolling through this a diagram came up on the screen and for me it was just clearly Mount Herðubreið, an iconic image in the northeast of Iceland. To me this image really was this mountain, familiar lines that were nonetheless supposed to be describing something totally different and strange going on in the Icelandic banks before the crash in 2008. When I looked at other diagrams in the report, other familiar “landscapes” started popping out. So there, from a distance and using my visual memory I chose a few of those and paired them to certain places in Iceland by looking them up on the Internet. This explains why the photographs are so grainy and unclear, but I found this visual pairing fascinating. I wanted to do this fast, and decided not to visit these places to take new photos myself. I just wanted to pair these as fast as I could.

G.T.

This was an important report that fell somewhat under the shadow of an eruption in Eyjafjallajökull only two days later. Everything happened fast and this was a strange period in Icelandic society. But there is another work that one is tempted to connect to the economic crash and the ripples that it left, and also to a serious earthquake that took place in Hveragerði in 2008 (6,3 on the Richter scale). This work, Tremors (2012) was recorded in an earthquake simulator in a shopping mall in Hveragerði and it is fitting to include it in this exhibition.

S.S.S.

Yes, this simulator interested me. The people that try it are always equally surprised by what happens even though they know what is going to happen, but the effects it has are very diverse. What we see is some sort of dance in the darkness, but this is a dance that is involuntary and the first impact of the “quake” is always a surprise. I wanted to see the same force impact many individuals in the exact same setting. Some start laughing, some stiffen up and others become very scared in this controlled environment. Maybe it is the same outside the box.

G.T.

Exactly, a rather scientific way of looking at things.

S.S.S.

Is this a case of scientific thought? Yes, maybe, a visual experiment in some sense. I connect this to the economic crash that took place shortly after this large earthquake in 2008. I was born and raised in Selfoss, a town that is on the same geological rift zone nearby and I remember being in earthquake training in school as a kid. An earthquake always comes out of the blue no matter how prepared you think you are, just like so many things in life. I see a certain resemblance between slow flowing movements, for example in economics and politics, and sudden shocks or events in life, even though the timescale is different. The tensions build up over a long period of time and then suddenly they need release somehow. For me this connection was important.

Looking over the works in this exhibition I spot a certain difference between the older and younger works. The older ones are often site dependent, made for a certain location where they were originally produced. Within them there is a greater sense of response to some external trigger, while the younger works are more carefully thought through. The older works also deal to a larger extent with the art itself, with the world of art and the role of the artist. This is something that I have moved away from in later works.

G.T.

Why do you think that is?

S.S.S.

There are no doubt many reasons for this, but I was more into a certain genre of contemporary art that is self- referential and deals with art and art history. This is of course just postmodernism when it is hard to read into works unless you are familiar with a lot of knowledge and citations. This kind of art can be great and I found this rather cool at the time, especially because it is not very feminine. Then you just relax after a period of this inward discussion with art and being an artist, and you realize that the discussion has to be wider and your intentions have to be something more than an inward critique, mine or for the field of art.

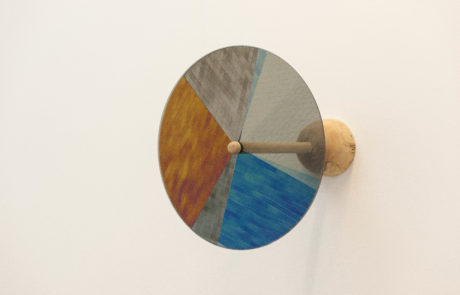

It can be said that the work Movements (2005), one of the oldest in the exhibition, is some sort of experiment in coming to terms with this inward discussion of art on the subject of art, and juxtapose it with a wider discussion of art within society. The work is a discussion between inner and outer forces and laws. It may be a good example of an equation that the viewer can figure out in many different ways.

I found it somewhat absurd that the curator, Inga Jónsdóttir, wanted to include older works in this exhibition but then it turned out to be very gratifying. You see things from a distance and you spot certain clusters of works in hindsight. My works that include “acrobats”, for example Upheaval (2004) where the artist is juggling wineglasses, were done during the boom years before the crash when artists were sometimes in the role of entertainers. Circumstances always have an impact on ones work. Travel, for example, was easier during the years before the crash and that is why exhibitions were made for specific sites. That way of working appeals to me, to work quickly and use what is available. The outcome is often site dependant works that no longer exist except in the form of documentation and therefore almost become a happening.

G.T.

But in the end this was okay for you to choose older works for the exhibition, you survived that?

S.S.S

Well, we will have to see about that, but at least it took some time to come to terms with the idea of dragging older works into the light and making the choices. Let’s say this has been an interesting process, and then others will have to evaluate the outcome.

G.T.

You also chose works from the collection of the L.Á. Art Museum in one of the rooms, correct?

S.S.S.

Yes, that is a very nice task. I remember the collection from when it was housed in Selfoss as I was growing up. There was a group of houses, schools, a swimming pool and different municipal museums, including the L.Á. Art Museum collection. I roamed between these buildings and took a visual arts class in the Art Museum, re-drawing the motifs in the paintings of Ásgrímur Jónsson, among others. There was also a yoga class in a room with his paintings on the wall. So this was very nice. Expanding your mind through meditation and the art of Ásgrímur Jónsson works very well.

G.T.

Thank you so much Sirra, and good luck.

About the artist:

Sirra Sigrún Sigurðardóttir (1977)

Sirra Sigrún Sigurðardóttir graduated from the Iceland Academy of the Arts in 2001, studied Art Theory at the University of Iceland for one year and received her master ́s degree from the School of Visual Arts in New York in 2013. She is an influential artist in Iceland and has participated in numerous exhibitions both at home and abroad, including the Reykjavík Art Museum and the Tate Modern in London, among other places. Sirra is one of the founding members and owners of the exhibition place Kling & Bang in Reykjavik, where she has organized numerous exhibitions and artistic events with the participation of national and interna- tional artists. In December 2012, Sirra was one of 24 international artists that Modern Painters magazine selected as artists to watch in the coming years.