Cyclone

Lilja Birgisdóttir · Katrín Elvarsdóttir · Eeva Hannula Hertta Kiiski · Marko Mäetamm · Tiina Palmu

May 24 – July 6, 2014

Mari Krappala

Cyclone is an audiovisual installation treating borders, real and imaginary. It searches out the occasions, actions, and thoughts that keep us in a lockhold and proceeds to the state in which we silently lose our capacity to imagine. From these impasses the narrative moves on to a possible confrontation with others or reflections on ourselves. It leads us to the threshold of circular motions that follow the rotational direction of the earth.

Birds sleep all around.

Wing strokes in the dark

and a movement: sudden,

unexpected.

A piercing noise.

Cries through the sky,

the air cut open

by sharp claws.

When the light pushes its way through eye lids,

the birds

fly away.

Scars quiver in the air.

(Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila 2007)¹

Cyclone is an area of closed, circular fluid motion rotating in the same direction as the Earth. This is usually characterized by inward spiraling winds that rotate anti-clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere of the Earth. In the Northern Hemisphere, the fastest winds relative to the surface of the Earth therefore occur on the eastern side of a northward-moving cyclone and on the northern side of a westward-moving one; the opposite occurs in the Southern Hemisphere. Cyclonic circulation is sometimes referred to as contra solem, without the sun.

Real and imaginary borders

When all exits are closed, instead of fleeing or fighting, both animals and humans learn to withdraw.²

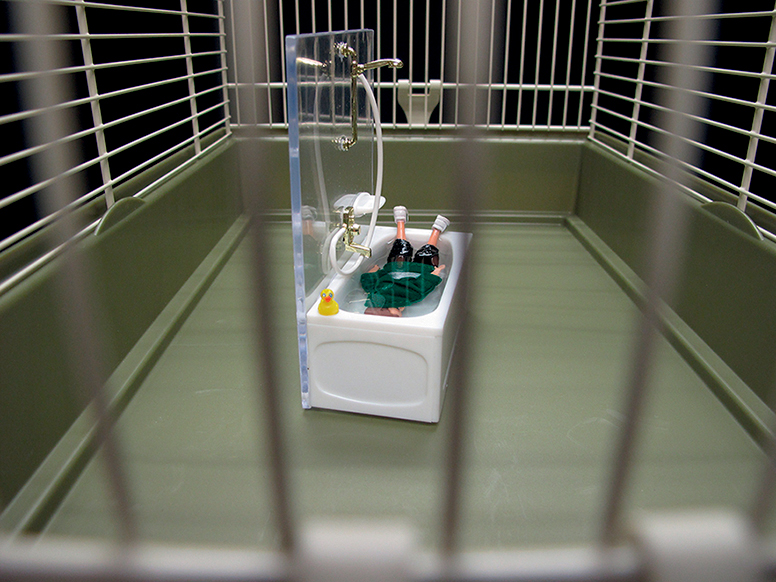

Julia Kristeva talks about abjection, which is close to the experience of uncanny or repulsion. The abject does not submit to the logic of definition. It creates a state of insecurity and wavering. Abject calls into question borders and threatens identity. Abject is on the borderline and as such it is both fascinating and terrifying.³ Marko Mäetamm’s installation consists of a number of small appalling scenes, rodent cages, of domestic violence decorated with little doll’s house equipment. The cages present dark episodes of life. Their melody is lugubrious and reviving.

Mäetamm says that these lovely little toy objects looked even cuter in the rodent cages, although the scenes were violent and horrid.⁴ However, there is light on the cages. As a process that determines borders between inside and outside, abjection can be understood as a spatial concept. In-between, composite and ambiguous, abjection is that which does not respect borders, positions and rules.⁵ Mäetamm’s cages do not stand on pedestals as static objects, but they swing on strings in the air, freely and possibly in slight motion.

The place of the abject is the place of the splitting of the ego. The abject implies an ego that repeatedly places, separates and situates itself and therefore strays instead of getting his bearings, desiring, belonging or refusing…instead of sounding himself as to his being, he does so concerning his place: ‘Where am I?’ instead of ‘Who am I?’.⁶ Mäetamm’s works deal with moments and situations where we are about to lose control. These are kind of blurry grey borderlines between two states of mind – equilibrium and imbalance among interdependent parts of our lives. We believe that certain events never happen to us because we know how to keep them away or unapproachable. Until they really happen to us.

Home as a territory plays an important role in Mäetamm’s works. Home is an ambivalent place. It is considered as the place that would offer us safety and comfort, the place where we can relax. At the same time home can be a place for both psychological and physical violence, terrifying crimes, horror and fear.⁷ Ultimately, the abject is identified with the maternal body since the uncertain boundary between maternal body and infant provides the primary experience of both horror and fascination.⁸ Encounters with objects happen in real life as well as in dreams and in art.

Confrontations and reflections with others or on ourselves

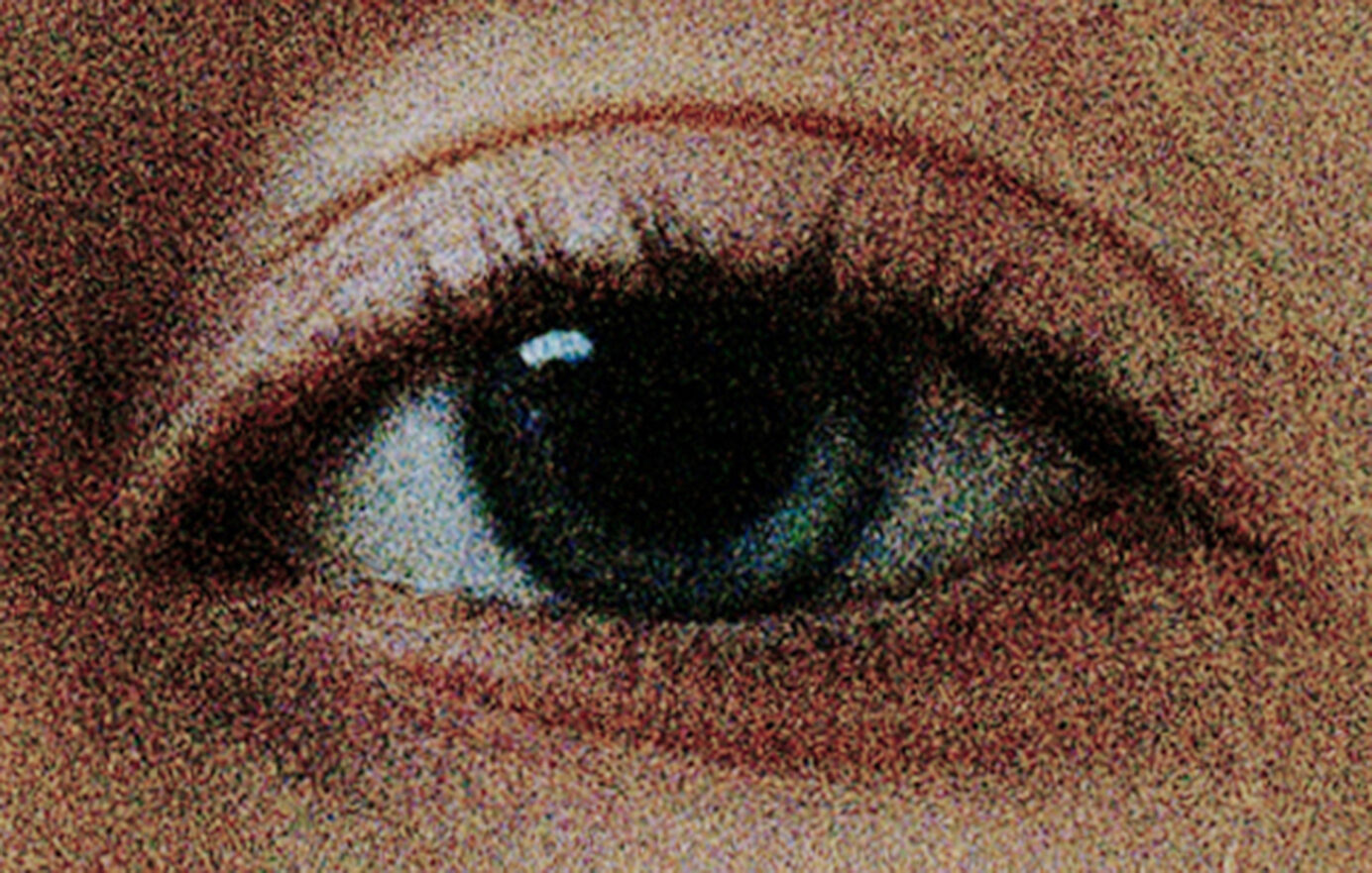

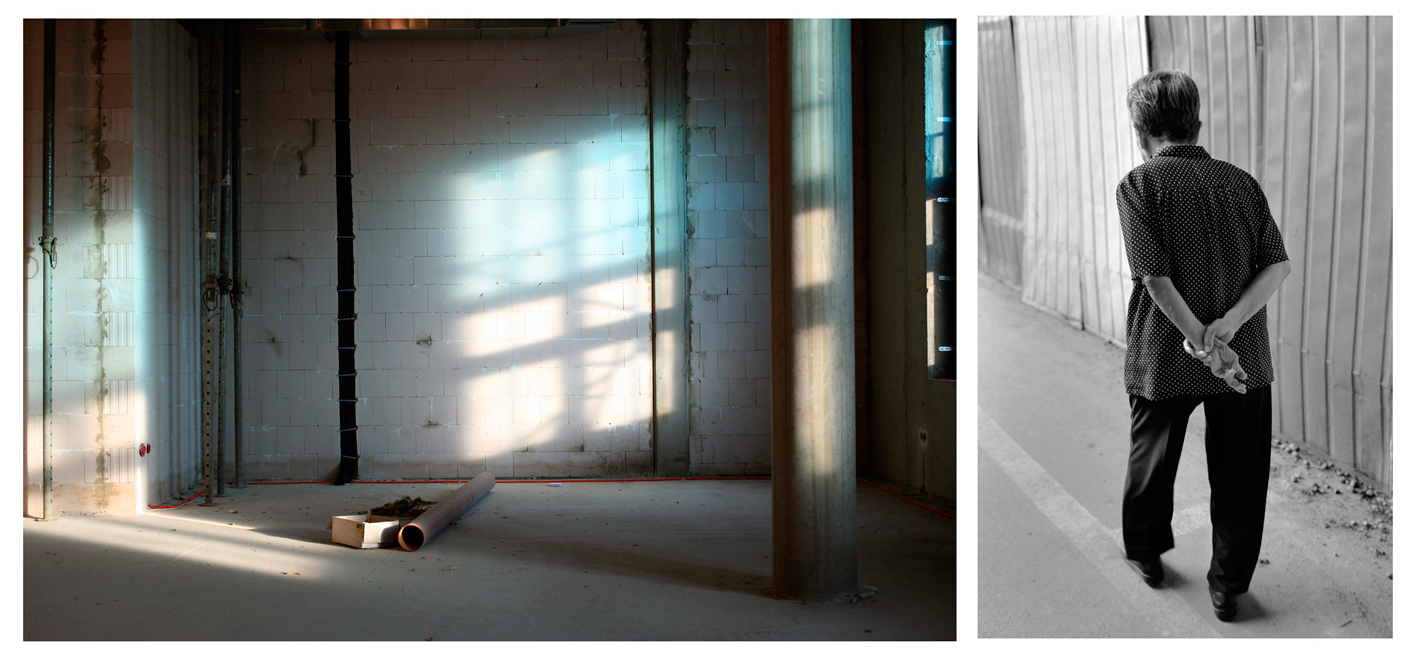

When we encounter an object, we reject things in ourselves that we cannot fully identify or understand. That is when we, in our minds, change into being the Other. However, it’s a question of something familiar, something forgotten or forbidden that again pushes into our consciousness. Katrín Elvarsdóttir’s images are of buildings under construction: barren walls, open doorways and windows. Sometimes buildings can be symbols of the human mind.

Elvarsdóttir’s photographs expose the literal borders that we construct between each other, the boxes and structures that separate people living their separate lives. If we don’t deny the abject, we can look for a meaning for it in the real world. If we want to, we can start to negotiate a place for it in our own lives. Elvarsdóttir’s photographs illuminate cold, hard surfaces, oftentimes with warm and soft sunlight.

Meeting with the ‘other’ can happen without consideration for space or time, as if in a play – but still very true. We are then in a zone of the imaginary. Elvarsdóttir’s photographs depict people on the street going about their busy lives. Seen from the back, a person’s body language becomes more visible – what we miss from their hidden faces is now gleaned from posture, clothing and contextual surroundings.⁹

Images can be fascinating and unreal, but their effect can be felt as very real. When we accept the ’otherness’ in ourselves, it also becomes easier for us to understand things around us, that which is unfamiliar or odd to us, strangers and other people.

Straying towards abjection is not only aligned with fear, but also with the fascination […] of moving towards the other and infinitude.¹⁰ In Eeva Hannula’s, Hertta Kiiski’s and Tiina Palmu’s two videos, cyclone is seen as a strong, scientifically motivated but what by its own logic seems to be uncontrolled phenomenon.¹¹ In a movement like the cyclone in the video, there is a question of dealing with grief and sorrow. In the Western world we often think that we can ultimately control them. In the first video blue pigment spreads in a bowl. The camera is still and the only movement in the video is made by the slow spreading of the pigment. Laws of physics determine this event, which seems to be random. In the video a logic that seems to be uncontrolled, much like that of Cyclone, is seen in a minuscule scale.

There is a primal Thing, which is to be conveyed through and beyond a completed mourning.¹² But the psychic requirement is not universal. Chinese civilization, for instance, is not a civilization of the convey-ability of the thing in itself, it is rather one of sign repetition and variation, that is to say, of transcription¹³ The Cyclone in the video is followed by chaos.

Hannula’s, Kiiski’s and Palmu’s second video is collage- like. It is the opposite to the minimalism of the first video. The image surface is rich and constantly broken by new images. The video shows a referential human figure making a rotating movement. The movement is intimate and personal. If we go back to the Western way of think- ing, we could ask ourselves why we have this need, almost the obsession to convey the primal object?

Kristeva¹⁴ maintains that in the obsession with the primal object, the object to be conveyed, assumes a certain appropriateness to be considered possible between the sign and not the referent but the nonverbal experience of the referent in the interaction with the other. I am able to name truly. The Being that extends beyond me – including the being of affect – may decide that its expression is suitable or nearly suitable. The wager of conveyability is also a wager that the primal object can be mastered. Hannula’s, Hertta Kiiski’s and Tiina Palmu’s video of the human puzzle contemplates the effect of cyclone, chaos. Ordinary people and their encounters with one another are seen as re-organized and fragmented, mirrored in each other. It is both a clear image and an encounter that still lacks clear logic.

The negation of fundamental loss opens up the realm of signs for us, but the mourning is often incomplete. It drives out negation and revives the memory of signs by drawing them out of their signifying neutrality. It loads them with affects, and this results in making them ambiguous, repetitive or simply alliterative, musical or sometimes nonsensical.¹⁵ Hannula, Kiiski and Palmu say that the video describes an inner experience that is never whole and consistent. The first video obeys external laws. In the second video the effect can be humanly internal, layered and seeking its own logic.

The threshold of circular motions

How does imagination return? How can one get out of a static situation? From where can a new movement be reborn? One possibility opens up in prosody. [It is] the language beyond language that inserts into the sign the rhythm and alliterations of semiotic processes. Also by means of the polyvalence of sign and symbol, which unsettles naming and, by building up a plurality of connotations around the sign, affords the subject a chance to imagine […]¹⁶

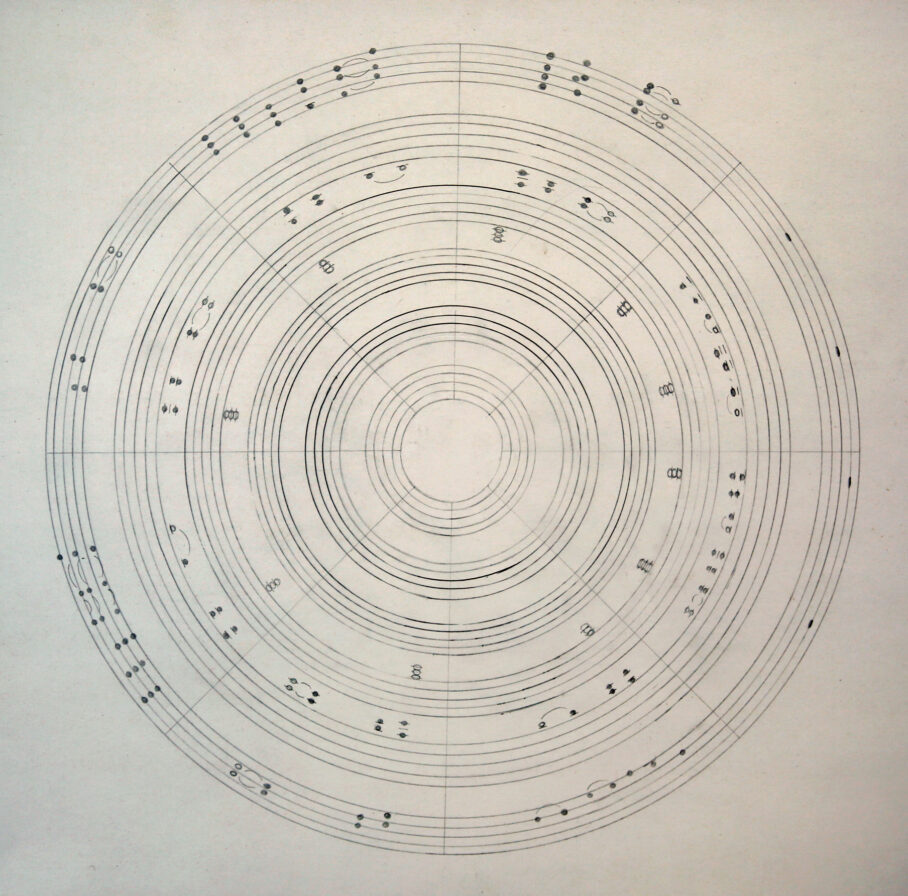

Lilja Birgisdóttir’s audiopiece circulates through the rooms of the exhibition space, sometimes disappearing and then starting again. It is a mantra with no beginning nor an end, with only cycles of meditative repetition. It hums invitingly as on the edge of a language, not yet quite transformed into words. Birgisdóttir quotes poet Emerson when describing the idea behind her audio- piece: ‘The life of man is a self-evolving circle, which, from a ring imperceptibly small, rushes on all sides out- wards to new and larger circles, and that without end.’¹⁷

Birgisdóttir says that her work calls us to lose ourselves to be found again in a vortex of sound and tones within a ritual that is at once ancient and contemporary – and to allow the sound waves to break on our bodies like waves upon a shore. Her work erases the boundaries between what we see and know and what we feel and understand. In the cycle there is unity and oneness whilst duality separates and disrupts. ‘You could close your eyes and listen to the primordial rhythm of your heart. A Zero is a circle, what appears to be nothing, turns out to be everything.’¹⁸

Lilja Birgisdóttir’s audiopiece can still be perceived as the melody of the Cyclone, in a way explaining why a possible abjection sometimes is consciously made visible, as can happen in art. Art might succeed in integrating the artificial language it puts forward (new style, new composition, surprising imagination) and the unnamed agitations of an […] self that ordinary social and linguistic usage always leave somewhat orphaned or plunged into mourning19. That way Birgisdóttir’s sound art tries to bring something to life, for which no verbal explanation has been found, first in the body, the imagination, then perhaps with the help of new languages, images or visual objects.

That kind of new movement opens up in inhaling, in tears or in a state between words. In a place where growth, renewal and change are possible.

Implausible fish bloom in the depths,

mercurial flowers light up the coast;

I know red and yellow, the other colors,—

but the sea, det granna granna havet,

that’s most dangerous to look at.

What name is there for the color that arouses

this thirst, which says,

the saga can happen, even to you—

(Edith Södergran, 1916)²⁰

Artists

Lilja Birgisdóttir

(b. 1983) studied photography in the Royal Academy of Arts, The Hague, Netherlands and received BA in fine art from the Iceland Academy of the Arts, Reykjavík, Ice- land 2010. From that year she has been a member of Kling & Bang, an artist run gallery in Reykjavik where she takes part in selecting artists and curating exhibitions for the space. In 2011 she founded Endemi, an art magazine about Icelandic contemporary art. Recent exhibitions include The Vessel Orchestra, opening act for the Reykjavík Art Festival in collaboration with ship captains of Reykjavík Harbour, May 2013 and The Balloon, Rawson Projects gallery, New York, this year.

Katrín Elvarsdóttir

(b. 1964) received a BFA from the Art Institute of Boston, Massachusetts, in 1993. Among her many solo exhibitions are Vanished Summer, ASI Art Museum, Iceland, 2013; Nowhereland, Reykjavik Art Museum, Iceland, 2010; Equivocal, Gallery Ágúst, 2010; Without a Trace, National Museum of Iceland, 2007; and Revenants, Seventh & Second Gallery, New York, 2003. Her work has also been shown in numerous group exhibitions around the world, including Germany, France, Finland, Sweden and Russia. Elvarsdóttir’s book Revenants / Proximal Dimension was published by 12 Tónar in 2005 (co-authored by M. Hemstock); her monograph Equivocal was published in 2011 and Vanished Summer in 2013 by Crymogea. In 2007 Elvarsdóttir was nominated for The Icelandic Visual Art Copyright Association’s Honorary Award. Elvarsdóttir’s works can be found in numerous private and public collections

Eeva Hannula

(b. 1983) is actually enrolled in a MA program in photography at Aalto University School of Art, Design and Architecture in Helsinki. Her work was included in several group exhibitions including Summer school, presented at the Finnish Museum of Photography in 2013 and Foam Magazine Talents exhibition at the Rossphoto in Russia 2014. She was selected as one of the artists for Foam Talent Call 2013 of Foam magazine.

Hertta Kiiski

Received her BA in photography from the Turku Arts Academy in 2012, and she is currently studying towards an MA in fine arts on the Time and Space Arts program of the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts. She is an artist who works in photography, the moving image and installation. Since 2009, she has had solo exhibitions in Finland and has participated in several group exhibitions in Finland and abroad.

Marko Mäetamm

(b. 1965) received his MA from Estonian Academy of Arts, 1995. He works with a wide range of media including photography, sculpture, animations, painting and text. Mäetamm tells us the stories which happen behind the closed doors and pulled curtains of the intimate territory we called home. He portrays the family as a little society -relaying through a dark humour the petty moments of daily life – and exploring the way our society manipulates the family dynamics through the macrocosms of economy, consumerism, and “quality-of-life” standards. His work explores the grey area where ambiguous feelings of being in control and being controlled merge. Marko Mäetamm has exhibited internationally both solo and group exhibitions and is represented by galleries in Estonia and London. He represented Estonia at the 52nd Venice Biennial in 2007.

Tiina Palmu

(b. 1984) received her BA from the Turku Art Academy, Finland in 2012. At the moment she is enrolled in a MA program in Finnish Academy of Fine Arts, Helsinki. She has participated in several group exhibitions, including Im12 at the Huuto gallery 2013, Helsinki and Aesthetics & Openings at the gallery Fafa 2014, Helsinki. She works with moving image, photographs and installations.

Curator: Mari Krappala

(b. 1968) is a writer, art theorist and curator. Her research, criticism and curatorial projects focus on contemporary art and her resent research deal with emphasis on articulations of borders, roots and rhizomes, real and imaginary ways of living with them. She is a docent of cultural and feminist studies in the Aalto University, the University of Art and Design Helsinki. Her PhD work dealt with contemporary art processes, photography and Luce Irigaray’s philosophy of the ethics of sexual difference. She teaches art theory, artistic research methodology and supervises MA and PhD works. At the moment she is doing curatorial work with independent art groups in the inter-artistic fields.