Foreign

Tinnu Ottesen

April 20 – June 5, 2017

Installations as art form are typically designed to change the spectator’s experience and perception of the particular space where they have been installed. As is often the case, the artist is dealing with existential questions, the language of art and its purpose for the spectator and the present time. By entering into the space, the viewer becomes both part of the installation and participant in it, whether active or inactive. Installations are generally local, being usually firmly linked to a specific place and space, but they can also be mobile like this one, where a certain idea and its realisation use the space as a reference point.

The exhibition Óþekkt (Foreign) by Tinna Ottesen is a two part space-installation that fills one of the rooms of the art gallery and demands the spectator’s participation. As far as this work is concerned, the space, the material, time and behaviour are significant – with “behaviour” referring both to the nature of the materials that have been used and, just as importantly, also to the reactions of the visitor who enters the installation. During the first stage of the installation, from 20th April to 18th June, the material used was plastic, while from 23rd June the material used is latex; the latter stage of the installation will remain in place as long as the material lasts, although not beyond 20th August. By thus dividing the installation, the effects of the space, material and time are amplified.

Whereas the two stages of the installation are independent of each other, people who manage to experience both versions acquire a stronger feel for the space, time and the behaviour of the materials used. The effects of a visit or a viewing are also always dependent on the individual, because one person’s attitudes and reactions may be different from those of others, and even an individual response may differ when walking into the same version of the installation at different times, because here, emotions, expectations and previous experience are significant.

Ottesen partitions the gallery into four specific areas. Initially, visitors are greeted with a defined, black-painted entrance with the installation emblem, a warning triangle, on the wall, along with a caution that the installation’s material will, in the end, collapse. Visitors are also invited to continue, and most do, out of curiosity. Now the visitor enters a darkened waiting room where a few people can gather before entering the main area, the work’s innermost core, which is only intended for one visitor at a time. While waiting, visitors can study footage of other installations in which Ottesen is working with the same ideas in similar installations elsewhere, along with images of the first stage of Óþekkt now that the later stage has replaced it.

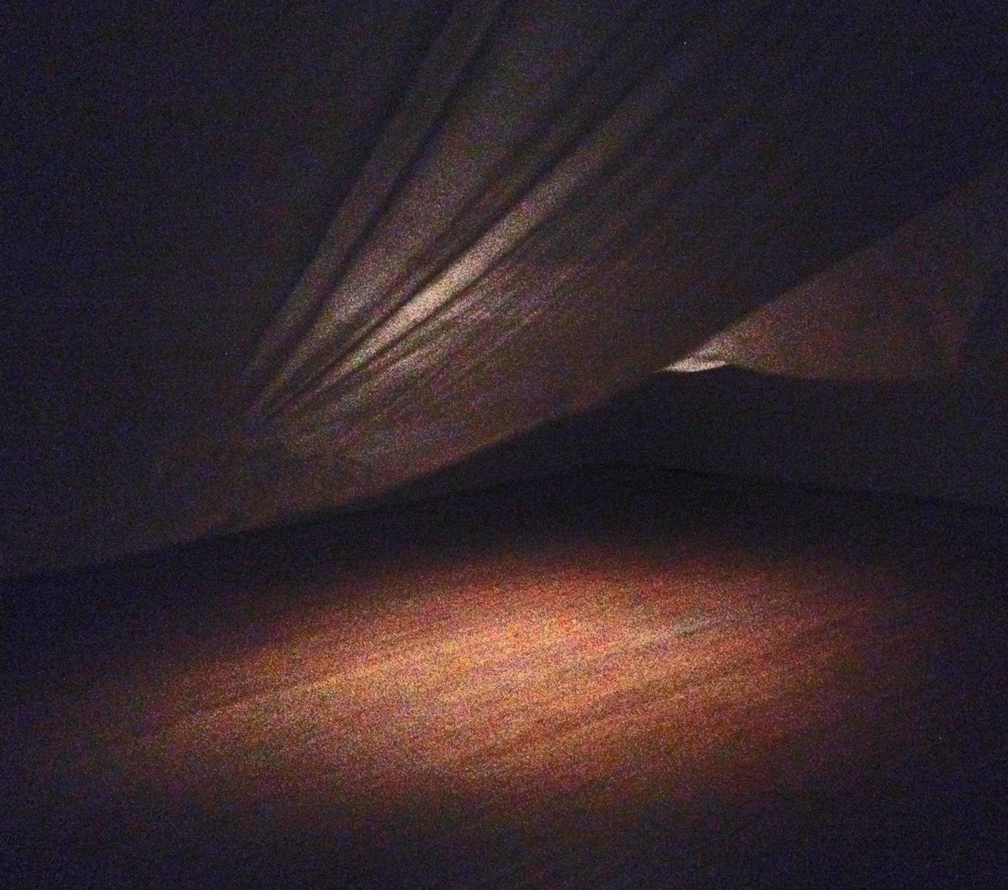

In the first stage of the installation, extremely thin industrial plastic divides the innermost space horizontally into two parts. Just offset from the centre of the space, three metal rings are suspended from the ceiling, one above the other. These are 300 cm in diameter, with the lowest one being 175 cm above floor level; above their centre is a faint light. A plastic membrane is fixed over each ring, with the topmost level having the largest area because the membranes are supposed to touch one another, and several litres of water have been poured into the top layer. Beneath this a plastic sheet divides the space in two; this is attached to the walls of the room at various levels, a little lower and a little higher than the height of an average person. As you walk into the darkened space, the plastic undulates according to the movements of the spectator, who can also make it move even more by making manual contact. As the plastic is opaque, the metal rings suspended from the ceiling are not easily visible unless you bump into them, but the light can permeate it, and you can feel the water and make it move.

In the later stage of the installation, the space of the innermost core is markedly different; this time the metal rings hanging from the ceiling frame the core space in a more visible way. Again, membranes are attached to the horizontal metal rings, but this time they are made of latex, which is stretched across the rings. Around the rings a vertical sheet of latex hangs down to the floor; the form visually resembles a gigantic drum or an oriental tent. Again, a few litres of water have been poured into the upper most membrane, and this time it is the material that yields to the weight of the water, and the layers touch one another. By entering the latex form you can touch the membrane and set the water moving. Again a dim light shines above it, and as the water moves, its reflection flickers around the ceiling of the room.

An element of the existential questions the work presents is contained in the use of materials (because the materials used behave in different ways) and in the visitor’s behaviour. Plastic is synonymous for many types of man-made materials that are mainly created from crude oil. It is not classified as a natural substance even though it consists of organic chemical compounds; the raw material is derived from fossilized animal and vegetable remains and is processed by “man”, who is certainly part of nature. Plastics arrived early in the last century and are now an all but integral part of existence. They were considered wonder materials that met the highest expectations, but as time has passed it has become clear that their properties are a threat to the biosphere, especially the way they break down – i.e. slowly and badly.

Latex is a well-known natural material that has been used in ancient cultures. Its main component is rubber, and its principal characteristic is elasticity. Rubber has also been developed synthetically, but around 30% of today’s production is natural. In contrast with synthetic material, latex breaks down easily. Another important element in both stages of this installation is water, the foundation of life.

The work as a whole also centres around the philosophical concept of the sublime, which has also been called in Icelandic ægifegurð (daunting beauty). That word well describes the feeling behind the sublime, because it comprises both admiration and threat. During the romantic period towards the end of the 18th Century, the sublime was frequently used in reference to nature’s terrifying force in contrast with man’s insignificance, while in modern interpretation it has been used to refer to the daunting force of technological advance that is both admired and feared by man. Is man part of nature or is he above it as he aims to control everything – and is that possible?

Due to wear and tear caused by visitors to the installation, the plastic deteriorated over time, and splits and holes of various sizes appeared, though not where the water was gathered. Repairs with wide transparent plastic tape were made on a regular basis, but this lessened the mobility of the plastic and the undulation became clumsier. Such a cheap material is more usually replaced than repaired, and these fixes became like scars on the work, which made its metaphor for nature, for example, even more powerful. As for the latex film, the water will eventually work its way through the material, which will, before that happens, gradually adopt the drop-shaped form of a teat – but how long will that take?

The work suggests a variety of metaphors for the relationship between man and nature that can be variously interpreted. On entering, visitors receive a warning because of the underlying threat of being doused in water if or when the material perishes. Hopefully the work will provoke philosophical speculation in the observer, because when successful the arts provoke more questions than answers, and it is up to the individual to seek them out and answer them. Is the person who enters Óþekkt in control of all circumstances? Is it the material that is foreign or is it the person who enters? Óþekkt therefore also deals with how one reacts to circumstances.

Is it safe to enter the work and what will the consequences be?

Tinna Ottesen

2002-2009 studied visual communications at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts Schools of Design and Architecture, and production design at the Danish Film School in Copenhagen. During her studies she was also an exchange student at the Iceland Academy of Arts for one winter and undertook work experience at Zentropa in Denmark. Tinna was accepted on a course at the a.pass school in Belgium (advanced performance and scenography studies), where she completed a post-master degree in 2016.

Since 2009 Ottesen has worked with diverse groups of creative people (artists, theatre artists, film-makers, musicians, designers) on a variety of projects, many of which have gained awards. This includes the Neo Geo group, who organised and performed an underwater concert at Reykjavík’s Sundhöll (“Swimming Palace”), a design project focusing on the centre of Hveragerði which gained an honorary mention, the documentary film The Gentlemen which was awarded the audience prize at the RIFF film festival in 2009, and Eins og í sögu (Storydelicious) during the DesignMarch festival in 2013, an installation combined with a light meal – an experience that stimulated all the senses and was awarded the Grapevine design award as the project of the year. Ottesen has worked on projects both in Iceland and all over Europe, most recently in Hamburg before her current installation Óþekkt here in Hveragerði.