In Step – Abstract Art

September 28 – December 15, 2013

The aim of the exhibition In Step is to offer visitors, especially school groups, insight into the development and broader context of abstract art. The spotlight is on geometric abstraction, a field in which Icelanders won international notice and kept step with other European artists. The exhibition title also refers to the merging of different artforms that abstract art espoused, though being In Step might seem contrary to the disorderly nature of radical change.

The arts are not an isolated phenomenon in modern times; they mirror society and also influence it, in Iceland as elsewhere. The modernist period, defined as the late 19th to late 20th centuries, encompasses the horror of two world wars, much political unrest and tension, amazing technological progress, and various philosophical probings, all of which affect our worldview. Prominent among the upheavals of modernism are the heated manifestos that artists made and advanced in journals devoted to culture and the arts. Thus modernism is synonymous with a variety of changes and developments but also describes a specific cultural stance, a zeitgeist, a position that people took on how the times were evolving. Within modernism many artistic movements emerged that spanned visual art, design, architecture, literature, and music. These art movements had many names but all originally belonged to the avant-garde, which is our name for movements that go the furthest in re-evaluating and rejecting older traditions. The avant-garde seldom has popular appeal but with the passage of time some of its offerings themselves become traditional and win acceptance.

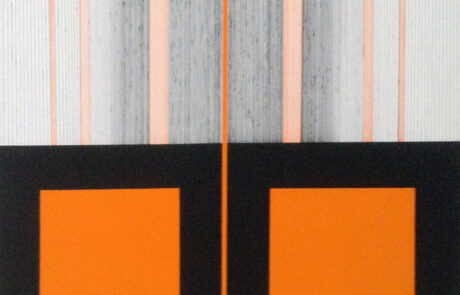

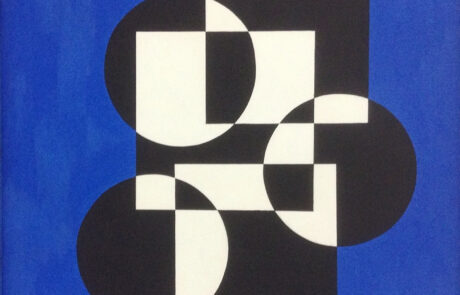

Abstract art began as an avant-garde movement taking its name from the Latin abstrahere, ‘to draw out from‘. Abstract art features the interplay of line, colour, and form rather than representations of the visible world. Abstract art branched out in many directions around the globe but has two main currents: geometric abstraction, which appeals mainly to a strict formal esthetic, and lyrical abstraction, which allows more room for individual emotional expression. To some extent the groundwork for abstract art was laid by two prior movements’ free-wheeling treatment of concrete phenomena, namely the evocative colours of expressionism and the formal dissections of cubism. Yet abstract art may also be traced to Wassily Kandinsky’s experiments around 1910. One thing he did was to study a representational painting wrong side-up, by which he determined that the pictorial subject made less difference than the freshness of the colour forms. He proceeded to paint pictures with no definite subject, pulling forms and colours from imagination in a search for inner beauty. Kandinsky was also a musician and drew theoretical connections between painting and musical composition; he reported hearing music on seeing colours. Lyrical abstraction sprang partly from Kandinsky’s experiments but was also influenced by the “automatic” drawing of the Surrealists. And others, too, were revolutionizing art. In 1915 the painter Kazimir Malevich introduced a new movement, suprematism, with his painting known as Black Square on a White Ground. The gist of it was that within creative art visual reality meant nothing; pure esthetic sensation governed composition through simple geometric forms. Straight lines symbolized man’s conquest over nature’s unruliness; the square was the central form because it is not found in nature. In the Netherlands, De Stijl arose, an artistic movement spanning many branches of art and design. Founded in 1917 by Theo van Doesburg, it had dwindled by 1931 but lived on in spirit in geometrical abstraction. De Stijl is simply Dutch for ‘the Style’. The movement’s goal was to develop an abstract art that would convey universal truth and thereby promote a new social order. Its style featured geometric forms, horizontal and vertical lines, and pure hues. Its best-known adherents beside van Doesburg were Piet Mondrian and Gerrit Rietveld. Van Doesburg turned up again in Paris in 1929, founding yet another school of art, Art Concret or concretism. Concretism proclaimed that art should not refer to, or symbolize, anything beyond its own concrete phenomena i.e. lines, colours, and forms. A painting’s subject was itself alone. Thus concretism features stark compositions, simple forms, pure hues, and flat picture planes. Concretism gained considerable currency in Scandinavia, where the term is used for geometric abstraction in general.

The ideology of the Bauhaus School, which was active in Germany from 1919 until the Nazis closed it in 1933, also had a broad influence that outlasted its years of operation, especially in the field of industrial design. The school was established by Walter Gropius as a school of art and crafts and as a kind of laboratory. Gropius gathered artists, architects, and designers from various avant-garde movements to teach and help conduct research on materials, combining different artforms, and the social influence of art. Students studied handicrafts as well as fine arts with an emphasis on mass production of items for everyday use. Geometric forms predominated; usefulness was emphasized over decorative value, a theme that would become central to the later movement known as functionalism.

Though abstract art was widespread in Europe by the 1930s it reached Iceland only after the War, via the work of Icelanders who had lived and studied in Paris, a bastion of geometric abstraction. In fact both Baldvin Björnsson and Finnur Jónsson had made earlier abstract works in Germany; in 1925 Jónsson had even shown such work in Iceland, but it had fallen on rocky ground: in Icelandic society landscape painting then reigned supreme among artforms. Svavar Guðnason’s 1945 exhibition is credited with having established abstract art in Iceland. Geometric abstraction swiftly gained the upper hand, due in part to the vigorous promotion of its theories in the catalogues of the September Exhibitions and the journals Vaka and Birtingur. It is also worth noting the strong showing by Icelandic women in the art of this era, e.g. the acclaim that Nina Tryggvadóttir and Gerður Helgadóttir won overseas.

In reading this sketch of the various movements within abstract art it must be borne in mind that their theoretical framework is more complex than this introduction implies and that one artistic movement does not refute another, as is the case with scientific theories; rather, artistic movements influence one another and replenish artists’ awareness of the possibilities of art.

Museum Director: Inga Jónsdóttir

In Step is the second of three exhibitions presented jointly by the Hornafjörður Art Museum, the LÁ Art Museum, and the National Gallery of Iceland. The aim of the series is to offer insight into three distinct periods of Icelandic art history. Further reading and projects for school groups are available, and visitors are invited to join in a game.

At Sea and on Land, the first exhibition in the series, explored the work of Gunnlaugur Scheving in order to illustrate an era when man and his activities became the subject of choice for Icelandic artists; Scheving’s abundant sketches also invited close study of the artist’s method. The third exhibition, scheduled for next year, will consider the novel media and diversity of postmodernism.

The works on display were not chosen as samples from individual artists’ careers but are intended to convey a particular era and ideology as an interesting and integral whole. We invite you to fall into step with us and recall, savour, and enjoy a by-gone era.

The following artists’ works are included in In Step:

Eyborg Guðmundsdóttir (1924–1977)

Gerður Helgadóttir (1928–1975)

Guðmunda Andrésdóttir (1922–2002)

Guðmundur Benediktsson (1920–2000)

Hörður Ágústsson (1922–2005)

Karl Kvaran (1924–1989)

Nína Tryggvadóttir (1913–1968)

Svavar Guðnason (1909–1988)

Valtýr Pétursson (1919–1988)

Þorvaldur Skúlason (1906-1984)

Of the many artists working between 1945 and 1969 the following may also be of particular interest in the context of this exhibition:

Ásgerður Búadóttir (1920)

Dieter Roth (1930-1998)

Eiríkur Smith (1925)

Hafsteinn Austmann (1934)

Hjörleifur Sigurðsson (1925-2010)

Jóhannes Jóhannesson (1921-1998)

Kjartan Guðjónsson (1921-2010)

Kristinn Pétursson (1896-1981)

Louisa Matthíasdóttir (1917-2000)

Sigurjón Ólafsson (1908-1982)

Sverrir Haraldsson (1920-1985)

Valgerður Briem (1914-2002)

Valgerður Hafstað (1930-2011)