Journey

Halldór Ásgeirsson

27. September – 14. December 2014

Æsa Sigurjónsdóttir, art historian

The art of Halldór Ásgeirsson and especially in the works that are now being shown in LA Art Museum is an extensive journal entry that provides insight into his experience of nature and the development of his own worldview. The exhibition is partly an index – and revisits the time Halldór began working as an artist. It is evident that the connecting thread has never torn and in more recent along with older works, different versions of the artist’s experiences with spontaneous writing, performance, and the natural materials of fire, water, and light that he began to work with early in his career, can be identified. In some cases he spends a long time with the results and transforms them into other materials: melted lava lumps become a shadow image, which becomes a drawing, and then again is transformed into a new material and different colour.

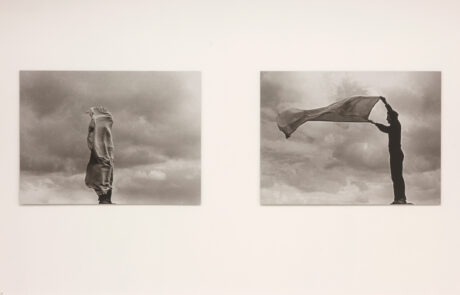

Reflecting on Halldór’s career it becomes clear that nature from the beginning has been a super-ego for the artist: nature, not as a subject – but the man’s environment. The experience and the insight awakened through that encounter are for him an endless subject and a source for creative production. His first works were murals carried out in the spirit of Neo-expressionism that was prominent with young artists, but foremost it was the need to mark the environment with individual symbolism, and a desire to use the body as an instrument that drew him into the turbulences of experimental and performance art.

Halldór acquired these working methods during his studies in France, where the art forms were rooted in the upheaval of the European art world around 1960 and after. He had landed in the boiling pot of the art revolution at Vincennes University just outside of Paris during the years 1977-1980. Halldór was accepted into the Experimental Department, which was likely the first art department within a university in Europe, long before art schools were transformed into art universities, or art discussed as research. There he was introduced to new perspectives on performance and the use of mechanical technology and new media for creation, and in addition students were introduced to the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard and theories about the imagination and poetics were injected straight into the vein.

The influence of the environment in which he studied first appeared in Halldór’s experiments with sign language, the use of the body, and spontaneous writing in his first solo exhibition at Gallery Suðurgata 7 in 1981. There “he painted himself” into the space and covered the venue in signs that later evolved into a personal alphabet and art language. More than a decade later Halldór revisited the idea bank that awaited him from his school years in Paris. The French artist Yves Klein was an important role model for the young artist who started to work with performance around 1980. When Halldór began to find his way with the experiments in fire and lava melting, he sought inspiration from the ideas of Yves Klein, the symbolism of colour and the hidden power within the expression of the body rooted in the mysticism of the Rosicrucian Order.

Halldór was able to reconnect his relationship with performance by disappearing into the research process of lava. He described the magnificent influence in a newspaper interview in the year 1995: “first and foremost this is a material that comes from the core of the earth and what captivates me is its rawness and the power that lives within it.”¹ The lava melting could be translated into a research method related to what the alchemists of the mid-centuries performed in the search for the philosopher’s stone. Previously Halldór had sought the symbolism of the elements and the interpretation of the Psychotherapist Carl Jung on the ancient thinking of the Middle Ages, the performance Metamorphosis executed in 1981 being an example. Jung’s theories of the existence of collective unconscious that can be referred to the origins of civilization seem to have a lot of influence on Halldór because he materializes Jung’s ideas on the transfer of the physiological processes into lava works and utilizes the transformation of various materials for endless creativity. The roots of this thinking can be found in alchemy – the medieval mystical chemistry in which gold arbitrators replicated the creative process of nature and transformed their knowledge of inscrutable signs.²

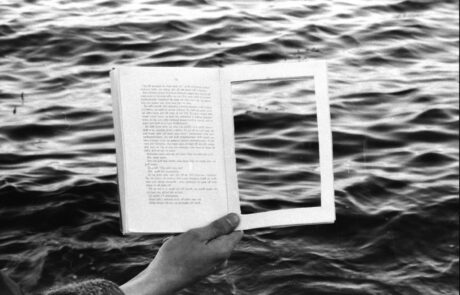

Here Halldór exhibits photographs, drawings, installations, texts, reconstructed older works, and pulls out records that he has collected in his career. The beginning is hidden in his personal experiences, but the outcome that appears in the exhibition reflects his journey through important periods of art history with the theories of Bachelard and Jung in his suitcase. The photographs are the part of the journal that Halldór has rarely shown. They are personal notes rather than work, their role is neither to show the country or places, but they are part of a registration of the artist in his travels around Iceland.

A number of artists in the 7th and 8th decades of the past century, such as Richard Long and Hamish Fulton, turned natural experiences of walking into art and installations that were brought into exhibition spaces, museums and galleries. They proclaimed simplicity and clearing the mind in the march within the land. Their work transforms nature and a relationship to the land sought by the common spiritual values of man outside of the economy of capitalism. Halldórs experiences of nature and his process refer to the same value. In his mind, it is important to be able to walk around and enjoy the land without owning it.

That said the museum or gallery can never fully contain nature, although it can be placed within it. Halldór’s lava reminds us of this fact. They do not deal in any direct way with nature and are also not a scientific study of it. Here, nature is perceived in a very primitive way, far ahead of the Romantic vision that has often characterized the relationship between Icelandic artists to the country.

The elements of fire, air, water, earth, or the four elements, were considered the roots of all matter. In alchemy, each plant had its place, each colour its own meaning, each element a role. Fire is a symbol of transformation and creation – water of emotions and poetics. Halldór believes that energy is the foundation of the world and in all his art existence appears as the diverse projection of this creative power. The works in the exhibition are a reminder of the fragile relationship between man and nature; they are an indication of how the artist has tried to capture nature to transform it into a utopian unity where nothing can be deconstructed. In the symbolic images one can see the wish to unite all language into one, or “to look for a word there that could even include the entire universe”³, which was the name of the work he exhibited in Hafnarhús in the autumn of 2003.

It was here that Halldór attempted to create a coherent cosmology from the disintegrating modern world. His work does not need to be read, they simply carry a specified date with the self.

1 Þórunn Helgadóttir, “Að vekja upp eldgosið”, Morgunblaðið, 28. maí 1995, B 15.

2 Ólafur Gíslason, “Efnafræði listarinnar”, Vikublaðið, 7. janúar 1994, 5.

3 Úr ljóði Sigfúsar Daðasonar. “Suður yfir Mundía- fjöll”, Hugleiða steina, Reykjavík: Forlagið 1997, 38.

Curator: Inga Jónsdóttir

Halldór Ásgeirsson (1956)

Halldór studied art at the University of Paris 8 Vincennes at Saint-Denis during the years 1977-80 and 1983-86. At his first solo exhibition in Gallery Suðurgata 7 in Reykjavik in 1981 attention was drawn to works based on the four elements: fire, water, air and earth, which have followed Halldór’s art practice ever since. On the same occasion he exhibited his first experiments with his own sign language, which has also continued to develop.

A turning point in Halldór’s art practice arrived in 1993 when he brought fire into contact with lava. By welding lava stone at 1200 – 1400 degrees the material melts and turns into a black enamel much like obsidian. Fast cooling in the atmosphere causes the lava to harden midway if it is allowed to drip. With this process Halldór creates fine black threads and glass-like pieces resembling organic phenomena that become the source for other works such as ink drawings on paper and installations. The lava-enamel led Halldór to experiments with water in glass containers and the projection of such onto the wall with light. These methods were developed further in collaboration with composer Snorri Sigfús Birgisson and later the music group CAPUT. They reached a peak at the World Expo in Japan in 2005 where six modern Icelandic compositions were jointly interpreted.

Halldór has exhibited in many places around the world; in museums, galleries, art centres, experimental art spaces and outdoor art exhibitions. In Shinto temple in Japan he melted the volcanoes Hekla and Fuji together in a performance. Halldór has worked on volcano works in France, Italy, Japan and China, and ahead is a project of the volcanic islands of Java in Indonesia and Sicily in Italy.