Layers of Time

Karl Kvaran & Erla Þórarindóttir

August 12 – November 13, 2016

“I have never understood the idea that a picture need necessarily be of some event, because so much happens in the picture. The picture is an event in itself.”¹

A conventional painting is an act or deed that consists in applying colour to a defined two-dimensional plane. The artist’s approach is unmediated, grounded primarily in his/her craftsmanship and skill, which imbue his/her ideas with life. Without the act of painting, there will be no painting. The brushstroke is the mark made by the act, encompassing both the subjective and the physical bond between painting and artist. The act of painting in itself becomes a part of the ideology and history of the painting, and hence inseparable from its nature. Thus within the painting is an inherent narrative to which the paintbrush is witness – and the painting on the canvas is its manifestation and the product of the act.²

“Painting aspires to become an act, and becomes an event,”³ maintained French artist and scholar Georges Mathieu (1921-2012), one of the pioneers of action painting, that emerged in the 1940s. After the symbolist period in painting, all that was left was the act, as the documentation of the environment evolved into documentation of the act. Mathieu termed this the “phenomenology of the act of painting.”⁴ The act is circumscribed by the time conserved in the paint- ing in the underlying layers of time, and the rhythm documented by the brushstroke.

The exhibition Layers of Time juxtaposes works by two artists: paintings made between 1968 and 1978 by Karl Kvaran (1924-1989) and paintings and sculptures by Erla Þórarinsdóttir (b.1955) from various stages of her career.

One of the qualities of the painting as a medium is the visibility of the technique. Karl Kvaran explored exhaustively the potential and elasticity of gouache, working in the medium almost continuously for nearly two decades from 1956. His works of that period are grounded in powerful line-drawing which would later play an important role in his oil paintings of the 1970s. He deconstructs the disciplined horizontal composition that typified his work in the 1950s, and undulating graphic lines progress rhythmically across the plane, as for instance in his Fugl næturinnar/Bird of the Night (1968) and Svartar samlyndar línur /Black Harmonious Lines (1968). The palette of the pieces is simple, predominantly black, while a blue under-layer can be glimpsed here and there, enlivening the surface.

Line also plays an important part in the paintings of Erla Þórarinsdóttir, in which it is the foundation of their formal development, together with colour. The works are based on line-drawing that swirls and turns the shapes, creating a three-dimensional impression. And underlying layers can often be glimpsed at the surface, which thus become vibrant and dynamic.

Karl Kvaran’s works are painted in many layers; at a casual glance they may appear to have a limited palette, but on closer examination the process and underlying layers of colour may be discerned through the surface. Erla often coats her works in silver-leaf – either covering certain shapes, or accenting specific features of them. On the surface glimpses may often be seen of the underlying drawing, paint and structure of the work, testimony to the process of its making. Drawing has an overt physical allusion to the motion of the artist’s hands.

Neither Karl nor Erla can be classed as an action painter in the sense in which the term is used in art history – as their methods are too disciplined and purposeful – but certain elements of their art have relevance to the methodology and ideology of the action painters.

Karl had no time for spontaneous art, being of the view that a work of art springs from the mind of the artist – that the artist grapples with the canvas, and the work of art is the result of that act – and that is how the magic happens.⁵ “The problem of painting, of building up a picture, that is first and foremost a matter of imbuing it with the life that consists in the internal expansion of forms and colours. It must be informed by the artist’s feeling for things, his judgement, and not by chance alone.”⁶

Most of Erla’s works are based on detailed ground- work in which the forms are carefully arranged on the picture plane. Precise choice of colours and the subtle nuances of tone gradually imbue the shapes with life and bring them into the world of objective reality, while also alluding to their own unfamiliarity and internal significance. Unlike Erla, Karl did not make sketches for his works, but allowed the painting to take shape as he went along: “It must all be unexpected, that’s the magic – that it happens unexpectedly.”⁷

A correspondence with action painting may be discerned in Karl Kvaran’s Form (1974), in which the artist’s rapidity and physical movement are displayed in a simple, fluctuating line which outlines a shape that is then filled in with a strong pink.⁸ In his Orðstír/ Reputation (1974) the circular form has opened up, and parallel lines undulate to the right, out of the picture plane. The artist also explores the circular form in Án titils/Untitled (1974), in which black line-drawing encircles a bright-red plane, bounded by a strip of blue and yellow planes that lend motion to the picture plane. The shapes curve into each other, forming a buoyant vortex.

Variations on the circle are also a recurrent feature of Erla Þórarinsdóttir’s paintings: rounded forms coalesce, intertwine or stand alone. In the series Einlínur/ Oneliners (2014) it is the interplay of hand movements and line that shapes the image. The flow of the line and the brush, propelled by the power of the moving hand possessed by total focus, forms an unbroken line. The works are made on aluminium sheets, which reflect the light and thus enhance the intensification of the colour. Focus and speed govern the continuous line-drawing in Silfureinlínur/Silverliners (2016), made in silver on white paper. Thus the artist works with the flow of movement in her body, transferring it to the delicate paper.

The transformation of material and its dynamics are an underlying element in Erla’s art. She has been working with silver-leaf for more than twenty years; by sheath- ing a certain part of the work in silver, new forces are brought into play. She utilises the silver’s potential and permits the material to take control. The oxidation process of the silver ensues, assisted by light, time and air. The oxidation period varies in duration: sometimes the artist leaves the work to oxidise for a year or more. The final result is not fixed until the artist intervenes and varnishes the work, halting the process of mutation.

This exhibition includes both new and older works by Erla, displaying how she has developed her use of silver, which may be said to be an identifying feature of her art. Silver’s light-sensitivity and reflectivity lend the works a new dimension and space, evoking the energy of the universe.

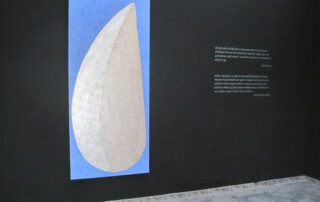

Erla’s Skel/Shelter (2016 ), in which a domed shell shape inlaid with silver-leaf expands across a pale- pink ground, engages in a dialogue with Karl Kvaran’s Form, both visually and in the physical energy of the hand movement to which the drawing testifies. The forms and symbols in Erla’s work spring from her interest in mysticism and oriental philosophy. Influence from various cultures may be discerned in works such as Austur-vestur/East-West and Vestur-austur/West- East (2016). Here she works on the one hand with continuous pattern under the silvered surface, and on the other with a silvery pattern on a deep-blue ground. The works are testimony to eternity and infinite space: they have an oriental ambiance which takes the observer on a journey to faraway places.

Subjectivity is one of the factors that the two artists have in common – colour, form, line, texture and technique combining to create abstract worlds – in addition to the confrontation with the medium per se, technique and the possibilities it offers. In Erla’s paintings a certain process of contemplation takes place: spirituality leads the observer through the fastnesses of the psyche and the interior of the mind. In his art, Karl invariably looked inwards, and the quest for purity and lucidity was the driving force in his art. “This art awakens a multitude of thoughts, and speaks not only to the brain but also to the heart,” observed author Thor Vilhjálmsson about Karl Kvaran’s art. ⁹

Layers of Time – the painting’s subconscious

Time as a process is one of the ongoing themes that are common to the work of Erla Þórarinsdóttir and Karl Kvaran. That theme focuses on time within the work of art, manifested in layers of time that appear in diverse ways in the artists’ work; those layers of time can be traced between the layers of brushstrokes. In Karl’s work they are defined by differing colour-layers of oils and gouache, while the silver-leaf Erla applies to her works oxidises over time and gains a golden sheen. Paradoxical as it may seem, layers of time may be said to be what unites the two artists, and also what separates them.

Karl Kvaran sometimes spent a long time working on one painting, repainting over and over, in such a way that the traces of the previous brushwork were discernible – what he called the life story of the painting: “The work takes me a long time, and often I over- paint, over and over again. That is the only thing that works for me. But it can give the paintings an added meaning – it means that they acquire their own life story, that can be glimpsed through the paint on careful scrutiny.”¹⁰ This method has been likened to the idea of a palimpsest¹¹ – an ancient Greek word for wax tablets, and later vellum manuscripts, on which mes- sages were written, and then erased to make way for new ones. The original lettering could, however, never be completely effaced, and traces remained visible through later layers. In other words, a palimpsest is a multi-layered document. The concept was first applied in a metaphorical sense by British essayist Thomas De Quincey (1785-1859), who related it to the complex phenomenon of the human mind and memory.¹² In his essay ”The Palimpsest of the Human Brain,” De Quincey wrote about the palimpsest as a phenomenon where different layers of text or meaning interact and seep into each other: “What else than a natural and mighty palimpsest is the human brain? Such a palimpsest is my brain; such a palimpsest, oh reader! is yours. Everlasting layers of ideas, images, feelings, have fallen upon your brain softly as light. Each succession has seemed to bury all that went before. And yet, in reality, not one has been extinguished.” ¹³

During a four-month stay at a studio in China in 2005, Erla Þórarinsdóttir had the opportunity to develop forms from her paintings into sculptures, which she made in one of the hardest substances known – black granite. ”It gave me the chance to develop the works in stone, to put into material form shapes that I had worked with in painting; in a sense it is a transfer to a tangible medium.”¹⁴ Erla showed these works in 2006 in her exhibition Duldir og dældir at the Anima gallery in Reykjavík, along with paintings and photographs. In the works Congenial and Samfella-kynslóðir/Generations the shapes almost fit inside each other, though separated by a narrow gap. Memory is forgetfulness, says Erla, likening the shapes and hollows with emotional models, which the observer can invest with his/ her feelings and meanings.¹⁵ Each feeling and mean- ing does not completely disappear, but leaves a trace or indentation, as De Quincey suggested with regard to the brain in the mid-19th century.

Novelist Guðbergur Bergsson writes of Karl Kvaran’s paintings that where colour or shape can be discerned underneath the surface layer of the painting, the artist is reminding the observer of the imperfection of all things – the painting’s past. “It is hidden, yet at the same time hinted at, by not quite painting over it, not obliterating every trace. What was painted over? Was it another ”rigorous” painting that was over-painted, another quest for perfection? Or is this an improvement, a penitence or a trend …”¹⁶ The mystery of the work becomes translucent; the unconscious of the piece can be seen. Hence Karl Kvaran’s work must be mostly read between the lines, writes Guðbergur.¹⁷

Similar ideas are expressed by Ethiopian painter Julie Mehretu (b. 1970), who is well-known in the USA for her layered abstract paintings. She says of her methods:

“Push, scratch, mark, cut, stay. A mark, a scratch, the sound of graphite, on paper, ink gliding out of nib pulled by fibers, in the paper, on the surface, of acrylic, like stone, like parchment, never tabula rasa, always palimpsest.” ¹⁸

In a painting there are thus underlying layers of time; it is built up layer by layer, on top of what went before. Hence time is preserved in the work.

In Erla’s art the handling of colour and material coalesces in the abstract forms. She makes detailed preparatory sketches for her works, but when it comes to the act of painting she gives herself up to the flow. She adds coatings of shimmering silver-leaf, while traces of form, line and colour can be seen in the underlying layer. The artist then leaves the work alone during the process of oxidation – and later comes back to it and varnishes it, halting the process that gives rise to the layers of time.

These clearly-discernible traces of the artists’ methods and craftsmanship give rise to a direct relationship be- tween the observer and the artist. On closer scrutiny, the underlying layer breaks its way through to the layered surface; the observer becomes a witness to the time-process of the works, the time they have taken to complete, the artist’s prolonged efforts, and perhaps his/her doubts. In Erla’s works different colours and under-layers can affect the oxidation process; in her view, the subject addressed in a painting is always, essentially, time. “It’s challenging, but always a little bit rewarding, to delay time in the way one does in making paintings. They have a sort of ambiance that has a powerful impact upon us, and that arises in part from the time that has been devoted to making them.” ¹⁹

The route to the objective

Many artists make their works in series, in which a specific idea or method is pursued, repeated and explored. By dint of repetition the artist seeks to grasp the idea and master it.

In his article “Cézanne’s Doubt,” French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) considers Cézanne’s battle with painting in his quest for perfection. Cézanne was known for working repeatedly with the each idea, in order to grasp it and the doubt that accompanied every brushstroke. Merleau-Ponty asks: “Why so much uncertainty, so much labour, so many failures, and, suddenly, the greatest success?”²⁰ As art historian Halldór Björn Runólfsson has pointed out, Karl Kvaran’s focus on research into form led him to work in series and repetitions, in which the artist exhaustively explored forms and colours.²¹ Great self-criticism and a quest for perfection may be said to have been the driving force in Karl’s art. ²² He spoke about the value of repetition: “In art one must often do the same thing over and over again, if one is to achieve a good result.²³ His gouache series are a telling example of such continuity of method: entities that test the interaction of colour, plane and line. The relationship between many of his works highlights this approach. The multi-layered ground is disrupted by line-drawing that is either flowing and organic as in Ljóð/Poem (1968), or spiky and sharp as in two un- dated works in a series of geometrical gouaches.

“It has always been important to me that there should be nothing superfluous in the picture plane. I strive to be as rigorous as I can in choice of colour and form.

I am quite certain where I am heading, but my quest continuously presents me with new problems. I can see in my mind how the picture should be. I start on it, and then perhaps it transpires that the forms don’t fit together well. They start making demands. They start arguing among themselves. I add another one. I change the colour; and precisely when I’ve managed to reconcile them, new problems crop up, and that requires the making of the next lot of pictures.”²⁴

Like Karl, Erla often makes her works in series. But her methods are characterised more by ideological content and the bond with physical energy, travel and different places. The works stand alone, while forming a relationship within a process of contemplation. The large paintings, made up of simple abstract forms, allude to meditation and to diverse cultures. The elasticity of the forms is tested as they fill the picture plane, or are entwined together like a pattern or network. Series of paintings such as Silverliners, Oneliners and Fake Money Paper entail a quest for an entity in which rhythm, flow and the actual act of painting govern the process and coalesce into a whole. Each painting thus becomes like a letter of the alphabet, or a word in a language, which can only be read in the context of the whole.

Within each work of art lies something specific, which the artist has placed there. Each work is unique, it is like a fount of constant visual stimulation and perception. The painting opens the way for the observer’s perception and subjective experience, which cannot be captured in an objective manner. Art thus deals with what cannot be said in words; it has its origin in the mind of the artist, who transmits his/her ideas to the observer through his/her art. Time consists in the work process that is preserved in the work of art, to which the brushstroke bears witness. The painting’s subconscious emerges in different time-layers, under- lining common factors in the art of Erla Þórarinsdóttir and Karl Kvaran – which each works with in his/her own way. Yet the painting must always, despite the artists’ very different methods, always “have its origins in the painter’s mind.“²⁵

Artists:

Erla Þórarinsdóttirwas born in Reykjavík in 1955. She studied art in Sweden, graduating in 1981 from the Konstfack University College of Arts, Crafts and Design. In that year she was also a guest student at the Gerrit Rietweld Akademie in the Netherlands. She lived for some years in Stockholm, where she was involved in running the ZON and Barbar artists’ galleries, while also working on her own art and design. She has travelled widely, and worked in New York, China and Morocco. Erla has held many solo shows and participated in group exhibitions in Iceland and abroad, and has received awards and grants for her work, e.g. from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation in 2000 and 2008. Era’s art is in private and public collections in Iceland.

Karl Kvaran (1924-89) was born in Borðeyri, northwest Iceland, in 1924. He studied at the private art school of Marteinn Guðmundsson and Björn Björnsson 1939-40, and at the evening school of Jóhann Briem and Finnur Jónsson 1941-2. After studying 1942-5 at the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Iceland Academy of the Arts) in Reykjavík, he went to Denmark, where he studied 1945-8 at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and at the private school of Peter Rostrup Bøyesen. From 1953 Karl regularly held one-man shows in Reykjavík, for instance at the National Museum of Iceland in 1968, 1969 and 1971. He participated in the September exhibitions in the early 1950s, and showed his work with the Septem group almost every year from 1974 to 1983. In 2010 the National Gallery of Iceland held a major retrospective of Karl Kvaran’s work.

Curators:

Aðalheiður Valgeirsdóttir (b. 1958) is an artist and freelance art historian and curator. She graduated in 1982 from the graphics department of the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Iceland Academy of the Arts). In 2011 she graduated from the University of Iceland with her BA in art history with a minor in cultural studies, followed by an MA in the same field in 2014. In her MA thesis, Pensill, sprey, lakk og tilfinning. Málverkið á Íslandi á 21. öld (Brush, Spray, Varnish, Feelings – Painting in Iceland in the 21st Century), she addresses the nature of painting, contemporary Icelandic painters’ approach to it, and redefinition of the painting with the advent of new media. At the start of her artistic career Aðalheiður focussed on printmaking and drawing, later turning to painting. She has held over twenty solo exhibitions and participated in many group shows around the world..

Aldís Arnardóttir (b. 1970) is a freelance art historian and curator. She graduated from the University of Iceland in 2014 with her MA in art history; she had completed her BA in art history from the same university in 2012, with a minor in cultural studies. The subject of her MA thesis is the Nordic art exhibition Experimental Environment II, held at Korpúlfsstaðir outside Reykjavík in 1980; her BA dissertation addresses the influence of Henri Bergson on the imagery of Icelandic painter Jóhannes S. Kjarval. Aldís has carried out research projects in visual art, and written exhibition texts for artists and galleries. She delivered a lecture at the opening of the exhibition Fletir at Arion Bank in 2015, and has recently been awarded a grant to research land art in Iceland.