TOHOKU

Through the Eyes of Japanese Photographers

February 1 – March 22, 2020

Recovery of the Jomon: Introducing “TOHOKU Through the Eyes of Japanese Photographers ”

Kotaro Iizawa

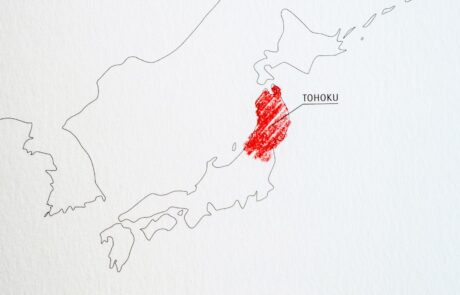

Tohoku is the northeastern section of Honshu, the largest island in the Japanese Archipelago. Its overall area is approximately 66,890 square kilometers and the population is 9.2 million. It is composed of six administrative units, the prefectures of Aomori, Akita, Iwate, Miyagi, Yamagata, and Fukushima. The region has a rather cold climate but is blessed with marvelous and abundant natural resource, so agriculture, fishing, and logging flourish there. It contains three national parks, Towada Hachimandaira in Aomori prefecture, Rikuchu Kaigan in Iwate prefecture, and Bandai Asahi in Fukushima prefecture. There are also two registered UNESCO World Heritage sites, Shirakami-sanchi, a huge area of beech forest that spreads from Aomori to Akita, and Hiraizumi in Iwate prefecture, which contains examples of architecture, including Chusonji and Motsuji temples, from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when it was a flourishing center of local political power.

In spite of its natural assets, Tohoku’s history can be seen as a series of disasters and hardships. In the Jomon period, from 15000 to 3000 years ago, when people begin living in the Japanese islands, the climate was warmer in Tohoku than it is now, and many archaeological sites have been found there that date back to this period. A large structure, measuring 10 x 32 meters and supported by six thicklogs 20 meters in height,has been discovered in the Sannai-maruyamasite of mid-Jomon, about 5000 years ago, in Aomori prefecture. More than 500 people are thought to have lived in this settlement for a span of 1000 to 1400 years. The pottery made during the Jomon period has unique flame-like forms, and the clay figurines look like aliens from outer space. These objects showthat the Jomon people had deep spiritual feelings and were able to express their thoughts and feelings very directly in physical form.

During the next historical period, the Yayoi, a cooling climate led to a decline in Jomon culture. The new agrarian culture based on rice cultivation, the Yayoi, led to a greater concentration of wealth. Political authority became centralized in the Yamato court in western Japan, and the Tohoku region came to be seen as backward and vulnerable to conquest and domination. Time and again during the eighth and ninth centuries, the Yamato court sent invading armies to Tohoku that were fiercely resisted by the native inhabitants of the region, known as Emishi. Tohoku was eventually organized into two provinces, Mutsu and Dewa, under the rule of the Yamato kingdom.

The location of central political power changed a number of times in subsequent years, but Tohoku continuedto be dominated and exploited by the central powers. Natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and tsunamis, have also been frequent in the region. Bad harvests often resulted from cold spells and droughts. From the central areas of Japan, Tohoku has always been seen as being on the periphery, a poor and backward region.This insidious prejudice remained in force even after the country became a modern state after the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

The fact that Tohoku was a marginal land,however, separated from the centers of politics and culture,made it possible to preserve local spiritual culture inspired by the mystical forces of life. Today, when modern material culture has reached an impasse and lost its vitality, there has been renewed interest in the spiritual traditions of Tohoku, which are characterized by a sense of liberation and serenity as well as humility toward nature and spirit. Kunio Yanagita’s Tono Monogatari (Legends of Tono), which marked the birth of folklore in Japan when it was written in 1910, is a record of folktales fromTono village in Iwate prefecture taken from the oral recollections of Kizen Sasaki, a native of the area. It depicts a world inhabited by strange supernatural creatures such as the tengu, kappa, and zashikiwarashi co-existing next to the ordinary human world. The style of these stories, which mixes fantasy with everyday life, was carried on by such writers as Kenji Miyazawa, born in Hanamaki, Iwate prefecture and Shuji Terayama, born in Hirosaki, Aomori prefecture.

In a sense, these explorations of Japan spirituality were way of recovering the Jomon culture that was thought to be lost. In Jomon no Shiko (Jomon Thought), published by Chikuma Shobo in 2008, archaeologist Tatsuo Kobayashima intained that Jomon villages were surrounded by hara, intermediate fields that where human maintained a symbiosis with nature. Hara did not exploit the bounties of nature like the farm fields of later times. They were sites of interactionand sharing with nature. In these areas, humans gathered food and hunted birds and animals while communicating and maintaining harmony with the spirits of the forest and the land. Sometimes they offered sacrifices to thank the spirits for their blessings.

Kobayashi believed that this interactive or symbiotic approach to nature is still retained in the hearts of today’s Japanese. “The Japanese view of nature and way of relating to nature were imprinted in the Jomon period. This attitude can still be glimpsed in everyday life and the annual cycle of popular festivals and rituals today, after the waves of westernization that struck during the Age of Civilization and Enlightenmentand again after the Pacific War and the recent upheaval of globalization.”It goes without saying that Tohoku is a place where this sort of “Jomon thought” is still alive and well.

This exhibition is composed of the work of nine individual photographers plus one group of photographers who have taken pictures of the Tohoku region. The chief motivation for organizing this show was the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake, which struck at 2:46 P.M. on March 11, 2011 with a force of Magnitude 9. The earthquake and the ensuing tsunami, over ten meters in height, caused horrific damage, leaving nearly 20,000 dead and missing, and was immediately followed by the unprecedented nuclear accident at the Fukushima No. 1 Reactor. These events were reported around the world, and the news was filled with place names from the Tohoku region, wherethe damage was greatest, mainly of cities along the Pacific coast in Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures.

Although many people were made aware of this incredible disaster, said to be unlikely to occur more than once in a thousand years, there was little reporting on the historicaland cultural background of the region. This exhibition is intended to fill that gap through the work of photographers. Tohoku has attracted many photographers since the technique of photography was introduced to Japan in the 1850s. After the 1920s, when inexpensive and easily operable cameras became available, the people of Tohoku began taking pictures of their own region. Following the Second World War, there was an increase in the variety and quality of photographs of the Tohoku landscape, people’s lives, and popular events. This exhibition presents a representative selection of such photographs.

Naturally, we considered the possibility of adding photos of the earthquake damage and subsequent recovery, but we decided to eliminate those photos from the exhibition. Plenty of these images have already been published in newspapers, magazines, and on the internet, and many books of photographs of the disaster have also been published. We did not feel the need to organize a special exhibition to show these pictures, and at the same time we were more interested in using photographs to show how the Tohoku region, which suffered so much damage, had developed prior to the earthquake. We hoped to reveal the heritage of Jomon culture remaining in Tohoku and show how it had been handed down, protected, and nourished. Because of this purpose, we included the work of Teisuke Chiba and Ichiro Kojima from the 1950s and 1960s as well as the work of contemporary photographers.

It should be noted that creating a category of “Tohoku photography” tends to diminish the uniquely individual qualities ofthe different photographers and localities. I myself was born in the city of Sendai in Miyagi prefecture on the eastern side of the Ou mountain range, which runs roughly north to south through the center of Tohoku. It is quite different from the area along the Japan Sea to the west in its natural features, customs, and living environment. The climate is comparatively warm in the Pacific coast region on the eastern side of the Ou Mountains, particularly in Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures. Culturally, these prefecture sare strongly influenced by the Kanto cultural area that includes Tokyo. The area on the western side of the Ou Mountains receives heavy snowfalls, and that part of Tohoku is connected more closely with the Kansai region, including the old capital of Kyoto, via ships that visit ports along the Japan Sea coast. These differences of climate and culture as well as the different interpretations of individual photographers have produced photographs that give quite different impressions of the Tohoku region.

In spite of these reservations, I believe there is validity in a category of “Tohoku photography” that transcends the individual differences of locale, historical background, and individual photographers. Below I would like to consider what this category might include while considering the works ofthe photographers in some detail.

Teisuke Chiba was born in Kakunodate in Akita prefecture. He began taking pictures as an amateur photographer while operating a kimono store in Yokote. His photos of the farm villages of Akita before and after World War II won prizes in photography contests and were carried in sections of photography magazines devoted to readers’ contributions, and his name gradually became known. In 1951 and 1952, Ken Domon and Ihei Kimura, who represented a movement of realism in photography based on Camera magazine, both visited Akita. Chiba was impressed by their concept of realist photography, the injunction to look directly at social reality and take “absolute snapshots that are absolutely unstaged.” In 1952, he organized the Akita Photographers’ Group and continued to focus on the lives of farmers.

If we look at Chiba’s pictures, we quickly see that they show more than a journalistic interestin their subjects. Heconsistently looks at the natural environment of Akita and the way of life of its inhabitants with a sensitive and affectionate eye. The resultant images reflect the photographer’s approach of moving in alongside his subjects while pressing the shutter release. The photographs reveal an inside view of Akita. “Up until now, I have cried and laughed with the farmers. From now on, I want to continue taking photos that make a social statement while exploring the things that make the farmers laugh and cry. ”This comment from an interview with a newspaper reporter in 1962 is a concise expression of Chiba’s ideas. His work was almost forgotten for a time after his death in 1965, but it has been revived and published in a number of books since the 1990s.

Ichiro Kojima was born in the city of Aomoriin Aomori prefecture in 1924. His father, Heihachiro Kojima sold toys and photography supplies but was also known as an art photographer. Influenced by his father, Ichiro had exhibited in photography exhibitions before World War II, but he began to take photography more seriously in the 1950s, following the war. In 1958, he held his first solo show, “Tsugaru,” in the Konishiroku Photo Gallery in the Ginza district of Tokyo, and he received high praise for his magnificent photographs depicting landscapes of the Tsugaru region of Tohoku and the people living there. In 1961, he moved to Tokyo in spite of the protests of people around him. He held his second solo show, “Freezing,” in 1962. In 1963, he published Tsugaru shi, bun, shashin shu (Tsugaru: Collection of Poetry, Prose, and Photographs) in collaboration with writer Yojiro Ishizaka and poet Kyozo Takagi. His future seemed promising, but his health was adversely affected by the unfamiliar life of the city. After a physically punishing photo trip to Hokkaido, he died at the early age of 39 in 1964.

Kojima achieved remarkable expressive power in printing his photographs, accentuating the contrast between black and white and sometimes simplifying the images until they were close to abstraction. His photos powerfully convey the harshness of the natural environment of a northern land. The body of work showing winter inTsugaru is especially impressive, conveying an inimitable solitude and sublimity. Kojima’s death can hardly be mourned enough; he was at the height of his artistic and conceptual powers and had just succeeded in developing a unique style when he passed away. The bold character of his imagery has been described as typical of “Tohoku photography.” A retrospective exhibition, “KOJIMA Ichiro : A Retrospective” caused a sensation when it was held in the new Aomori Prefectural Art Museum in 2009.

Hideo Haga became a freelance photographer when the company where he worked was dissolved in 1952, and he spent the next 60 years or more photographing folkloric subject matter. This interest, which became his life work, was prompted by a lecture he heard from folklorist Shinobu Orikuchi while a student at Keio University. His fascination with folklore increased as he explored the heart and mind of the Japanese people in popular festivals and rituals. He established an excellent reputation with the photobook Ta no Kami (God of the Rice Fields), published in1959, which vividly depicted the religious ceremonies conducted by rice farmers.

Haga was energetically engaged in taking folkloric photographs throughout Japan. Allof his work was informed by the sense of urgency expressed in his introduction to Ta no Kami: “Now is the last chance to record the religious observances connected with rice farming.” It is a fact that Japanese agriculture, forestry, and fishing went into decline during the period of high economic growth that beganin the 1960s, and the village communities that supported the festivals and rituals of folk religion were rapidly dissolving. For this reason, Haga’s folkloric photographs provide valuable documentation for tracing the dramatically changing conditions of Japanese life.

The works by Haga in this exhibition depict the festivals and performing arts of Tohoku. They demonstrate that Tohoku is a treasure trove of traditional religious practices that have been carried on for a very long time. While these photographs can be seen merely as detailed documentation of festivals and ritual observances, they express an ineffable sense of mystery, as if revealing the presence of gods descending from their world to this. Although Haga takes a dispassionate and rational approach, itis obvious that he feels great excitement when shooting the festivals of Tohokuis apparent.

Masatoshi Naito is an other photographer who is obsessed by the gods of Tohoku. He studied applied chemistry at Waseda University and then worked fora fiber company but quit his job in 1962 to become a freelance photographer. He became interested in Tohoku as a subject after visiting Mt. Yudono, part of the Dewa Sanzan (three mountains of Dewa) range in Yamagata prefecture in 1963. There he had the unsettling experience of seeing the mummies of Buddhist priests who had died while fasting to save starving farmers. While photographing the mummies, he explored the philosophic background behind their unusual practices and became captivated by the folk religions of Tohoku, especially the Shugendo (a syncretic Buddhist sect known for its ascetic practices carried out in the mountains) of Dewa Sanzan. Naito went on to publish unique folkloric studies in addition to his work as a photographer.

Naito’s Tohoku photobooks, including Baba Tohoku no minkan shinko (Old Woman: The Folk Religion of Tohoku), published in 1979, Dewa Sanzan, published in 1980, and Tono Monogatari (Legendsof Tono), published in 1983, evoke a sense of strange presences, ordinarily invisible, about to emerge from the dark background. With the help of a strong strobe light that reaches deep into the darkness, Naito attempts to capture the forms of another world inhabited by gods and demons. The works shown in this exhibition are close-up images of Buddhist statues found in the temples and shrines of Dewa Sanzan. They were previously published in Dewa Sanzan to shugen (Dewa Sanzan and Shugen) published in 1982. The strange, vivid faces express the robust faith of common people in the local mountain religion and the life force of Tohoku earth that has been preserved since ancient times.

Hiroshi Oshimaa book of photographs called Koun no machi (The Town of Luck) in 1987. The title is taken from the novel La Ville de la Chance by Elie Wiesel, a writer born in Sighet in the Kingdom of Hungary (now part of Romania). Oshima’s book is composed of three parts, “The Town of Luck,” “Sanhei,” and “Spring and Asura.” The first part, “Town of Luck,” contains photographs taken by Oshima, who was born in Morioka, Iwate prefecture, between the 1950s and 1960s while he was attending junior high and high school. The second part, “Sanhei,” contains photographs taken in the 1970s and1980s, inspired by the peasant uprising that took place in the Sanhei area (at that time, part ofthe Nanbu domain) of Iwate prefecture in the mid-nineteenth century. The third part, “An Asurain Spring” (the title of a collection of poems by Kenji Miyazawa), contains photographs mostly taken inthe 1980s. Although each part is independent, the whole is structured like a single chain of light and shadow. Freely moving back and forth between the distant and recent past, we can trace Oshima’s personal history and the natural and cultural environmentof Iwate, where he was born and raised.

The photographs in the section entitled “Town of Luck” are particularly fresh and dazzling to the eye. Cows with their calves, a small child, a ceremonyin which a boat is burned on a river, street events (festivals, demonstrations, a parade of cars celebrating the marriage of the crown prince), a picnic on the Koiwai Farm – all these things and events have a mythical feel. As we proceed to the second and third parts, images overflowing with the joy of photography gradually become painful and traumatic. Together, however, they eloquently demonstrate that “Ihatov,” the imaginary name given to Iwate prefecture by Kenji Miyazawa, is a blessed land of a bundant water, light, and air. Anyone looking at these images is likely to associate them with the remembered landscape of their own hometown.

As stated at the beginning, the landscape of the Tohoku region is incredibly beautiful. Cherry blossoms in the spring, the green leaves of summer, the colored leaves of autumn, and the white snow of winter – these varied features of the seasons bring dramatic changes, creating a marvelous and breathtakingly spectacle. Japan can be proud of the natural beauty of its mountains, rivers, oceans, and forests, and Tohoku boasts some of the most remarkable natural beauty in the country. Naturally, many photographers have taken brilliant landscape photographs in the natural environment of Tohoku. One who has attracted a great deal of attention in recent years is Meiki Lin.

Lin has a somewhat unusual background; he turned to photography after studying medicine in college. Beginning in the mid-1990s, he distinguished himself as a landscape photographer withhis superb technique and sensitive powers of observation. His books of photographs were highly acclaimed, including Mizu no hotori(At the Edge of the Water), published in 2001, Mori no shunkan (Momentin the Forest), publishedin 2004, and Shiki no takaramono (Treasures of the Seasons), published in 2011. In 2007, he participated in a three-person show at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, “Meditations of Gaea: New Horizons in Nature Photography,” with Tetsuo Kikuchi and Takayuki Maekawa. He was seen as one of the most promising photographers in this area of photography. As can be seen by the works in this exhibition, showing the mountains of Tohoku, Lin’s work has a magnificent decorative beauty along with great energy and dynamism. The landscapes of Tohoku combine rugged masculine power with a sense of the ephemeral, delicate, and transitory. In my view, Lin’s photographs provide us with a new way of looking at Tohoku.

Masaru Tatsuki, born and raised in Toyama prefecture, worked as an assistant in a rental studio while teaching himself photography. Between 1998 and 2007, he took photos of trucks decorated with flamboyant paintings and lots of flashing lights, known as “art trucks” or deco tora(Japanese for “decorated truck”). The resulting photobook, DECOTORA, was published by Little More in 2007. Tatsuki began photographing the Tohoku region when one of the deco tora drivers, who happened to come from Tohoku, introduced him to a deer hunter there. While taking portraits of people he met in Tohoku, including matagi (professional hunters), fishermen, and housewives, Tatsuki, like Hideo Haga and Masatoshi Naito, became interested in folk religion and festivals. Looking at the images of the shamanesses called ogamisama in Kesennuma, Miyagi prefecture and the dancers doing the Natsuya deer dance in Miyako, Iwate prefecture, it is clear that the vibrant energy hidden in the dark depths of Tohoku is still pulsating today.

It was just when Tatsuki was thinking about publishing these photographs that the great earthquake struck Tohoku. The book, published under the title Tohoku, came out after a brief delay with two additional photographs shot after the earthquake in July 2011. Folklorist Norio Akasaka contributed a text to the book in which he wrote, “The people, things, and landscape drip with blood and reek with the smell of flesh. Whether this is intended by Tatsuki or not, they definitely turn our gaze toward an animalistic Tohoku.”

Tohoku is like a wounded animal, but although it is bleeding now itwill rise again bursting with life. Tatsuki’s photographs convince us of the possibility of this outcome.

The Sendai Collection is a series of rather unusual photographs compared to the others in the exhibition. It is the result of a photographic project started by a group of photographers living in Sendai, Miyagi prefecture in 2001 under the leadership of Toru Ito. The current members are Toru Ito, Shiro Ouchi, Makoto Kotaki, Wataru Matsutani, Hidekazu Katakura, Hisashi Saito, Ryuji Sasaki, and Reiko Anbai. The group divided up areas on a map by drawing lines and decided who would work in each area. They then photographeda wide variety of structures in their respective areas, including houses, roads, and bridges. The photographers made their own decisions as to the position and angle from which the photographs would be taken, but they photographed the entire landscape in which the structure was placed, avoiding a subjective viewpoint as much as possible. Another condition they set for themselves was to keep the entire image in sharp focus. The purpose of their project was “imprinting negatives with anonymous landscapes that are being lost day after day and making a record of them.” The project began with the aim of forming a collection of ten thousand photographs. It is still underway, but the number of photos has already reached six thousand.

Many landscapes were about to be changed forever by urban development and the demolition of deteriorating houses, and Ito hoped to preserve their memory in photographs for future generations of people living in Sendai. But the significance of the project was suddenly changed bythe great earthquake of March 11, 2011. Many of the structures seen in the photographs shown here were destroyed or seriously damaged by the earthquake. The act of recording landscapes as they exist here and now is always attended by an urgent sense that the structure may soon be lost. Houses and buildings are containers that hold the lives of the people living there. If we take a fresh look at these houses and roads, seeing them as witnesses to the way of life of the inhabitants of a certain city in Tohoku in the early twentieth century, we will realize that these “anonymous landscapes” have important things to say to us.

NaoTsuda traveled the world, questioning the meaning of looking at landscapes in his photographic practice. He attemptedto have a virtual experience of the flow of time from antiquity to present and future and the chain of lives of the people living in those times. In a representative photobook, SMOKE LINE, 2008, he traced the flow of a “river of wind” and captured the landscapes of Morocco, China, and Mongolia in expansive images. In the next book, Storm Last Night, 2010, he shot ancient archaeological sites in Ireland, which he saw as “early buildings in which humankind separated the world between the inside and the outside. ”I was pleasantly surprise to learn that he had begun photographing Jomon-period sites inTohoku region from 2010. If we consider his intentions in seeking the sources of ideas and images from an anthropologist’s point of view, it may seem natural that he would explore “the original form of rituals in the basic culture of Japan” in the sites of the Jomon period.

The photographs by Tsuda in this exhibition do not directly show Jomon sites or artifacts. Rather, they present scenes in which ancient and modern Tohoku come together and resonate with each other. Looking at images of Namahage, an unusual custom from the Oga Peninsula in Akita prefecture, and the fire festival of Hayama Shrine in Tomioka, Fukushima prefecture, it is apparent how much the Jomon spirit has entered into the spiritual environment of Tohoku as a “basicculture.” Tsuda approaches photography like an archaeologist digging into the deep layers of the earth, discovering things that may have been seen by the Jomon people. The work he shows here takes the form of an interim report, and we can look forward to watching the results of his continuing fieldwork.

The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake came as an especially great shock to Naoya Hatakeyama, who was born in Rikuzentakatain Iwate prefecture. Rikuzentakata, which is located on the Pacific coast, was almost totally destroyed by the great tsunami. Hatakeyama’s family home was swept away by the tsunami, and his mother lost her life. Previously, he had written,“The sky, the sea, the mountains, the water, the light, and even photographs are disinterested in human beings, and the thing called nature leads us to a tremendous sense of helplessness” (Underground,2000). The disinterest of nature in the enterprises of human beings was vividly revealed by the earthquake.

Hatakeyama met this bitter experience with a strong response that involved his entire being as a photographer. He presented an exhibition, “Natural Stories,” from October to December 2011 at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, in which he assembled representative works of the past and added two newphotographic series. His images of the post-disaster landscape in Rikuzentakata and Kesengawa (KesenRiver), were produced as “photographs made as precisely as possible with careful use of composition, color, and light beams.” The latter is included in this exhibition.

Kesengawa is emotionally restrained in comparison to previous work; it is an attempt to depict the subject matter coolly and accurately. For Hatakeyama, it was a rather unusual series. He did not originally intend to exhibit this group of photographs, which includes private scenes, the riverside landscape near his family’s house, festivals, and members of his family, taken from 2002-2010. The earthquake, however, gave them much greater significance. Most of the scenes shown here have been literally or physically lost. More than that, however, I believe that Kesengawahas an inherent fascination as a series of images showing the everyday life of a city in Tohokuin great detail, speaking slowly and clearly like a parent talking to a child. Hatakeyama gave the title Petit Coin du Monde, “ a small corner of the world,” to a box in which these photographs were placed. This series expresses a universal vision of great import in spite of its seeming casualness.

The work of these nine individual and one group of photographers illuminates Tohoku from a variety of viewpoints. How it is received will depend on each viewer of the exhibitionand there is no need to suggest how it should be seen.

From this body of work, however, we can get a real sense of a vaguely emerging condition of “Tohoku photography.” As I have frequently noted, Tohoku is a region where Jomon culture, a formative culture for the Japanese people,continues to have a strong influence. The Jomon people developed a unique world view on the stage of the hara, the field where the space of human life and the natural environment outside it come together in symbiosis and interaction. The photographers mentioned here have sensitively responded to places that correspond to the hara, scenes where outside and inside, the sacred and the secular, the dead and the living call to each other.

If Jomon thinking is to retain its liveliness and vitality, it may be necessary to keep some distance from the forces of globalism, which homogenizes and forces a rigid order on everything. Tohoku may have certain advantages for achieving this end since it is perpetually on the periphery, the edge seen from the center of power. “Tohoku photography” is supported by a strong desire to remain on the edge. The photographers shown here have explored a territory on the other side of an invisible boundary through the eye of photography, a different way of looking at things.

Perhaps Tohoku could be treated as a universal concept rather than just the name of one geographical area in Japan. Tohoku, or the northeast, could existanywhere. The Tohoku of Europe is Russia, and the Tohoku of Russia is Siberia. The significance of taking a new look at the world from the periphery, standing on the edge, can be considered in the context of diverse locations. I believethat the “Tohoku photography” introduced here should be seen in this greater context.

Kotaro Iizawa

Photography critic. Born in Miyagi prefecture in 1954. Received PhD in art at the University of Tsukuba in 1984. Served as editor of photography magazine déjà-vu from 1990 to 1994. Major books include Shashin bijutsukan e yokoso (Welcome to the Photography Museum) (Kodansha, 1996), Sengo shashinshi noto (Notes on the History of Postwar Photography) (Iwanami Shinsho, 2008), Shashinteki shiko (Photographic Thinking) (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2009), and Afutamasu shinsaigo no shashin (Aftermath: Photography After theEarthquake) (NTT Publishing, 2011).

Artists:

Teisuke Chiba

Born in Kakunodate, Akita prefecture in 1917. Spent his entire life in Yokote, Akita prefecture. Taught himself photographywhile working as a kimono merchant. Shortly after World War II, began winning prizes in the monthly sections of camera magazines devoted to readers’work. In spite of his amateur status, became a central figure in Akita photography. Most of his photos reflect his affection for Akita, recording the customs and way of life of local farmers in this region known for heavy snows. The postwar movement of photographic realism, led by Ken Domon and Ihei Kimura, had a great impact on Chiba and other photographers in Akita. Ambitious photographers’associations were organized, such as the Akita Photographers’Group (founded in 1952, name changed to Group Akita in 1954), and their images combined humanism with a direct presentation of reality. Chiba’s documentary photographs of farm villages in the 1950s and 1960s were some of the freshest and most brilliant produced by this group. Chiba died of stomach cancer in 1965 at age 48. Friends and colleagues arranged a posthumous exhibition of his photographs at the Fuji Photo Salon in Tokyo in 1966 and published Teisuke Chiba isaku shu (Collected Photographs of the Late Teisuke Chiba). Renewed interest in his work has emerged in recent years.

Ichiro Kojima

Born in Aomori in 1924, the son of a merchant dealing in toys and photography supplies. Graduated from Aomori Commercial High School and was drafted into military service during World War II. After the chaotic postwar period, began working seriously as a photographer in 1954. Photographic subjects were typical landscapes of Tohoku –the yard of a Tsugaru farmhouse or a solitary road blasted by a winter wind. Discovered by Yonosuke Natori, a pioneering journalistic photographer, who admired Kojima’s abilityto produce images transcending everyday life with a superb formal sense and expert technique. Given first solo exhibition at the Konishiroku Photo Gallery in Tokyo in 1958. In 1961, moved to Tokyo with the ambition to become a professional photographer. Received the New Artist Award from Camera GeijutsuMagazine in 1961 for The Rough Seas of Akita, a photo published the same year. Kojima’s career seemed promising but he fell into a slump after moving to Tokyo. Visited Hokkaido in 1963 in the hope of reviving his work, but difficult conditions there damaged his health. Published the only book containing his photographs to be published during his lifetime, Tsugau shi, bun, shashin shu(Tsugaru: Poetry, Prose, and Photographs), that same year. Died at the early age of 39 in 1964. Kojima felt great empathyfor people living in the harsh environment of Tohoku and created remarkably forceful prints with skillful use of mask printing and reproduction. His photographs have been featured in numerous exhibitions after his death, and his reputation continues to grow.

Hideo Haga

Born in Dairen, China in 1921. Influenced by ethnologist Shinobu Orikuchii of the Keio University Faculty of Letters. Founding member of the Japan Professional Photographers Society, started in 1950. Photographs festivals and traditional performing arts in Japan and other countries. Has taken photographs in all parts of Japan and 101 foreign countries. Served as producer of Festival Plaza at Osaka Expo 70 and has been involved in many other events and activities. Major publications include Ta no kami(Gods of the Rice Fields) (Heibonsha, 1959), Nihon no matsuri(Festivals of Japan) (Hoikusha, 1991), and Nihon no minzoku jo, ge(The Japanese People, two volumes) (Cleo, 1997). Awards include the Silver Medal of Honor from the city of Vienna, Austria in 1988; the Purple Ribbon Medal in 1989 and the Order of the Rising Sun, Fourth Class in 1995 from the Japanese government; and the Cross of Honor for Science and Art from the Republic of Austria in 2009.

Masatoshi Natio

Born in 1938 in Tokyo. Became a freelance photographer after graduating in applied science from Waseda University and working for a fiber company. Photographed the mummies of Buddhist priests who had died fasting for the salvation of starving farmers in Dewa Sanzan and began making photographs that concentrated on the folk religions and ethnology of Tohoku. Received the New Artist Award from the Japan Photo Critics Association in 1966. Participated in “New Japanese Photography”(The Museum of Modern Art, New York) in 1974 and “Beyond Japan”(London Barbican Art Centre) in 1991. Solo exhibition “MASATOSHI NAITO Photography and Folklore”(Kichijoji Art Museum)in 2009. Won 2ndDomon Ken Award for his book Dewa Sanzan and Shugen(Kosei Publishing Co., 1982).Other books of photographs include Ethnological studies include Miira shinko no kenkyu(Study of the Mummy Faith) (DaiwaShobo, 1974) and Tohoku no sei to sen(Tohoku Sacred and Profane)(Housei University Press, 2007).

Hiroshi Oshima

Born in Morioka,Iwate prefecture in 1944. Attracted attention with the Sanheiseries (1973-1977, Tanohata, Iwate/Ohashi Gallery, Tokyo) on the theme of a place in his home region wherea peasant uprising erupted in the Edo period. Received the Prize of the Society of Photography for photobook, Koun no machi(La Ville De La Chance), in 1987. Received 28thIna Nobuo Award for exhibition, “Thousand Faces, Thousand Countries –Ethiopia,”in 2003. Started journal of photography criticism, Shashin sochi(Photographic Apparatus) (Gendaishokan, 1980), for which he served as editor. Books of photographs and commentary include Koun no machi(1987), Shashin genron(Phantom Theory of Photography) (Shobunsha, 1989), Aje no Pari (Atget’s Paris) (Misuzu Shobo, 1998)etc., Edited Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography Library, Re-recorded Commentary on Photography 1921-1965 (Tankosha, 1999), 101 World Photographers(Shinshokan, 1997), etc. Many photography exhibitions include “Map of Tairajima Village”(PUT, Kagoshima, 1975-80) and “dah-dah-sko-dah-dah To Kenji Miyazawa”(Petit Musee, Tokyo, 1996). Presently serving as steering committee member of Nikon Salon, trustee of the Tokyo Goethe Memorial Museum, professor at the Graduate School of Fine Arts, University Faculty of Fine Arts, Kyushu Sangyo University, and instructor at Kuwasawa Design School.

Meiki Lin

Born in Yokosuka, Kanagawa prefecture in 1969. Began studying photography on his own at age 18. Held photography exhibitions at Fuji Photo Salons in various locations in Japan, including “Mt. Amakazari”(1998), a famous mountain located between Niigata and Nagano prefectures, “At the Edge of the Water”(2001), on the beauty of water and unique landscapes associated with water in Japan, and “Moment in the Forest”(2004), on the forests of Japan, “Chikyu (hoshi) no tabibito”(Meditations of Gaea: New Horizons in Nature Photography) was organized by Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography in January 2007 and later traveled to Matsumoto City Museum of Art and “Arata naru takami e”(To a New Height) was organized by the Fukushima City Museum of Photography. Published photobook, Treasures of season (Nihon Shashin Kikaku, February 2011), exploring landscapes throughout Japan with a digital camera, and presented exhibition of the same title at Canon Galleries. Member of photography jury for the East-West Art Ward 2011 in London. Donated photographs to the 2011 India-Japan Global Partnership Summit in Tadami. Continues to take photographs that express the subtle sense of atmosphereand transparency of natural landscapes. President of Meirin Co., Ltd., instructor at Club Tourism International Inc., manager of Kibo Photographers photo school.

Masaru Tatsuki

Born in Toyama prefecture in 1974. Became a freelance photographer andinterested in artfully decorated trucks in 1998. Spent the next 9 years photographing art trucks and drivers, publishing the photos in DECOTORA(Little More, 2007). “DECOTORA”solo show at Little More chika in Tokyoand TAI Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, U.S.A. (2008). Took photographs in the Tohoku region from 2006 until 2011 and published them in Tohoku(Little More, 2011), for which he won37thKimura Ihei Memorial Photography Award in 2012.Now concentrating on Tohoku as a lifelong subject, continues to visit the region, speak to people, and take photographs while showing respect for nature.A number of photographs from the DECOTORAseries were acquired by New Mexico Arts, a division of theNew Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs.

Sendai Collection: Toru Ito, Shiro Ouchi, Makoto Kotaki, Wataru Matsutani, Hidekazu Katakura, Hisashi Saito, Ryuji Sasaki, Reiko Anbai

Sendai Collection is a group of photographers living in Sendai organized by Toru Ito. Their aim is to preserve views of ordinary landscapes in the city which are eroding in the flow of time and about to disappear from memory. They started their project in 2001 with a goal of taking 10,000 documentary photos of existing landscapes. In order to produce these records they set rules –eliminating subjectivity and artifice from their photos and avoiding the use of lens effects such as blurring or perspective.They have held 15 exhibitions in Sendai and published two volumes of the book Sendai Collection, vol. 1 in 2005 and vol. 2 in 2007.

Nao Tsuda

Born in Kobe, Hyogo prefecture in 1976. Completed a BA and a post-graduate course in photography at Osaka University of Arts. He has traveled around the world, taking pictures of encountering landscapes, places, and people with his “device of photography,” which might be described as having undertaken the task of exploring “images transcending time and space” and “the origin of images.” Approaching photography as contemporary art, his style of deeply treating both old and new themes makes him seem as a truth seeker of arts. The reputation of his tranquil works is growing within Japan and abroad, and he has held solo exhibitions in New York, Paris, and Frankfurt in recent years. In Japan, “SMOKE LINE,” presented at Shiseido Gallery in 2008 attracted a lot of publicity. He was awarded the Minister of Education Award for New Artist in Fine Arts in 2010. His publications include Kogi(Rowing Out)(MONDE BOOKS, 2007), SMOKE LINE(AKAAKA, 2008), Coming Closer(AKAAKA+hiromiyoshii, 2009), and Storm Last Night(AKAAKA, 2010).

Naoya Hatakeyama

Born in Rikuzentakata, Iwate prefecture in 1958. Trained by KiyojiOtsuji at the School of Art and Design, University of Tsukuba. Completed graduate studies at the University of Tsukuba in 1984. Began living and working in Tokyo, producing a series of photographs focusing on the relationship between nature, city, and photographs. Received attention for photos of lime mines and of architectural spaces and canals in Tokyo. Received 22nd Kimura Ihei Memorial Photography Award and 42nd Mainichi Award of Art in 2001. Has participated in many solo and group shows in Japan and abroad. Chosen as a representative of Japan at the Venice Biennale in 2001. Major recent solo shows include “Draftsman’s Pencil,”The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura in 2007 and “Natural Stories,”Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography in 2011, HuisMarseille, Museum for Photography, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2012. Major books of photographs include LIME WORKS (Synergy inc., 1996, amus arts press, 2002, Seigensha, 2007), Underground (Media Factory inc., 2000), Naoya Hatakeyama (Hatje Cantz, 2002), Ciel Tombé (SUPER LABO, 2011), and Terrils(Light Motiv, 2011). Photographed the destruction in his hometown caused by the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake in 2011.