Thoreau’s World

November 16, 2019 – April 26, 2020

Ásthildur B. Jónsdóttir

We face a climate emergency that is a consequence of irresponsible actions, excessive consumption, injustice and unfair division of resources among the residents of the earth. We know that the situation is dire, and that man made climate change is escalating by the day. The results of numerous studies demonstrate to us how fragile the ecosystem is, and how perilous the situation may become. The young generation is imploring governments and the public to take responsibility, and reminding us that mankind has only this one planet.

While 202 years have passed since the birth of environmentalist, naturalist, writer and philosopher Henry David Thoreau, his ideas about the relationship between man and nature have rarely been more relevant than they are today. He pointed out the importance of moderation in human actions, so as to avoid disrupting the balance between nature‘s productive capacity and what is consumed. He foresaw the consequences of unchecked and irresponsible utilisation of natural resources, and he has been an influence on thinking about nature conservation.

In the exhibition Thoreau’s World at the LÁ Art Museum, three women artists of different generations address Thoreau‘s ideology as expressed in his Walden, or Life in the Woods. The book is inspired by his own experience of turning his back on urban society to live alone in the woods on the banks of Walden Pond in Massachusetts, USA.

The main theme of Thoreau‘s book is clear: if one‘s desires and expectations in life are simple and modest, life can be easy, pleasant and happy. The consumerist rat race – an unrelenting quest for things of which we have no real need – is often the source of people‘s problems.

Thoreau was captivated by the constant process of change in nature. Living by the pond, he contemplated the water‘s manifold changes. He searched for the meaning of life, all alone surrounded by nature, for two years, two months and two days.

He had that demarcated world all to himself, and there he found the opportunity to consider the purpose of life. He relished his experience of the gentlest, the tenderest, the most innocent, the most exhilarating of what natural phenomena can provide. In the woods he learned to live with the seasons and comprehend the vagaries of the water. By learning to understand himself in the woods, he felt that no place on earth would ever seem alien to him again.

Thoreau moved out into the woods because he wished to learn what life could teach him. It is human nature to learn to understand oneself. And that focus on self knowledge was not Thoreau‘s discovery: the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates stressed that the individual must know him/herself, and on the front wall of the temple of Apollo in Delphi were the words KNOW THYSELF. The philosophical principle is by its nature absolutely vital, for it implies that a person must live in accord with him/ herself; and in order to do so, he/she must develop his/her own moral principles. Walden, or Life in the Woods sheds light on Thoreau‘s musings on why it is important to know nature from one‘s own experience, in order to be equipped to protect it.

Thoreau‘s experiment is not only closely linked to these age old ideas which may be traced back to the Greek philosophers; it also ties in perfectly with what we today call mindfulness. According to Ian Morris, mindfulness is a matter of creating a space for one self to take a step backwards and explore who we are, away from the hustle and bustle of daily life. In his writings Morris explains that mindfulness can be simple or difficult in practice. The pursuer of mindfulness can quite simply focus his/her attention on the present moment and what is happening around him/ her, just as Thoreau did out in the woods. There he also mastered the more rigorous phase of mindfulness, i.e. to focus attention on one spot, instead of allowing the mind to wander. Thoreau learned to observe the changes in the water from season to season, and to feel the rhythm of nature; he said that as he walked through the woods at Walden he felt connected to his sensory organs. And he remarked that there was no point in going out into the woods if his mind was occupied with anything else than what was to be found there.

Thoreau’s World is curator Inga Jónsdóttir‘s endeavour to bring together the work of three women artists of different generations into a significant entity. The outcome is an installation which plays upon the senses, leading the observer to consider the broad context where physical, symbolic and spiritual worlds meet. The artists‘ endeavours constitute an intriguing assemblage, although they did not need to move out into the woods in order to find their bonds with nature. All the works have a clear connection to the environment – whether in Hildur Hákonardóttir’s braided tussocks, Elín Gunnlaugsdóttir’s cockcrow, or Eva Bjarnadóttir’s implements and connections.

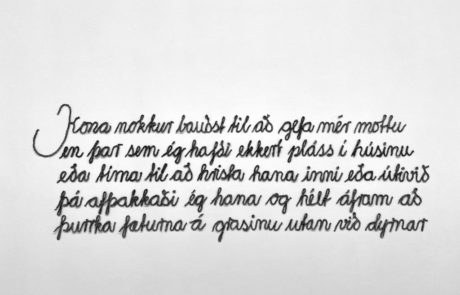

The message of Hildur’s work is metaphorical; like Thoreau she permits herself to use feelings as arguments in addressing natural phenomena. She applies the old traditional craft of braiding mats – which in Thoreau’s day was a common way of using up scraps of cloth and yarn. The mat signifies man-made consumer goods, which are per se unnecessary when one lives out in the woods. Thoreau’s choice of a mat to symbolise the unnecessary is something of a paradox – and Thoreau himself admits that his views are sometimes paradoxical. According to Hildur Hákonardót tir “the mat itself is a remarkable phenomenon. In our homes it has the role of demarcating the indoor space from the outside world, often inscribed with a message such as Welcome, signifying hospitality. It is on the border of two worlds. The mat thus marks a boundary, like a stream flowing through a landscape.” In the installation Hildur has formed a quotation from Walden in cursive lettering made of slender braids. Part of the work consists of shapes made up of sewn together braids in earthy tones, which are placed against the walls down at the floor. They may thus signify either conventional mats, or tussocks in a landscape.

A video work of movement in the woods demonstrates that, like Thoreau, the artist has given herself time to engage in a dialogue with nature, working with the fleeting moment in a leisurely manner: the emphasis is on the interplay of natural shapes of leaves and the breeze that flutters through them.

By spending time in nature we experience the slow movements of the leaves. The wood is alive. It has its own tempo, as if it has something to whisper to us. Life of the same kind is seen in Hildur’s ink sketches on thin rice paper made for the book. Wilting plants and brushstrokes reminiscent of a little pile of seeds in the right hand corner of the work entail a promise of possible life after death. Hildur, like Thoreau, is familiar with the seasons: she captures the feel of autumn, as the small plants that grow in Icelandic nature remind us of the importance of relishing the transience in the environment, which remains unnoticed by so many in modern society.

We may not necessarily notice gradual changes that take place in nature, or in the language of other lifeforms not directly connected to the human scale – such as the slow effects of toxicity, or the time it takes for substances to break down and decay. Organic handtools made by Eva Bjarnadóttir using lupin pulp evoke craft traditions and the idea of time, while also referencing the way that the lupin, originally introduced into Iceland to fix barren volatile soils, has spread and put down roots. The lupin is an invasive species that takes root wherever it can – just as humans tend to do. In nature we may often find signs that people have passed through, and in cyberspace “footprints” are also left behind in the form of emojis. These modern day memorials, such as smileys and “frown” emojis, have also been moulded in lupin pulp by Eva, and arranged into a bouquet which is displayed in a vase in the foyer. In her The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt‘s New World, Andrea Wulf refers to Thoreau’s meditations on whether his writings will ever be better than the notes he makes in his journal. He likens his words to flowers, and asks himself whether they are best displayed in a vase (i.e. the book) or growing in the wild (i.e. the journal). Tools and emojis are implements used to elucidate the world on the basis of measurements and technical data. In daily life some emojis are an essential yardstick for the posts made on social media. The emojis grow like weeds, like the lupin in the real world. Social norms are then expressed in terms of the number of “likes” and emojis each post attracts, measuring the response to the post. Eva’s contribution is thus a critique of the obsession with constant measurements. Thoreau pursues similar ideas, evaluating the lyrical, yet doubtful of his own judgement – and asking whether it is justifiable to subject everything to measurement and assessment. In his book he displays a desire to combine a lyrical approach with the scientific.

Despite Thoreau’s close connection with nature, he was in a sense an intruder there. The connections drawn by Eva from the book, and written in earth tones on the floor, are delicate, like nature. They resemble bridges between two worlds, like the interplay of the flowers and the vase. The same is true of the language, which in its own way is slippery; Eva focuses on the small: “Conjunctions have no meaning as such, but provide a vital bond in the language, like stepping stones across a brook, or stitches in a garment.” The ripples on the floor engage in dialogue with Hildur Háko nardóttir’s video work, and are a reminder of the importance of slowing down. Eva may be said to have undertaken an experiment similar to Thoreau’s when she returned to Iceland from Amsterdam three years ago, and made her home in the Öræfi region of the southeast. She lives there in a small space, as Thoreau did, in order to seek a deeper connection with nature and with herself. Unlike Thoreau, however, Eva does not see this as a short term experiment; but in both cases conditions are created for re-evaluation.

Elín Gunnlaugsdóttir’s audio work and its presentation are based on found sounds and objects. Thoreau loved the sound of cockcrow; although he had no livestock at his cabin in the woods, he “thought that it might be worth the while to keep a cockerel for his music merely, as a singing bird.”

In the work Elín plays upon the observer’s senses, making Thoreau’s dream of a cockerel wood come true, with a healthy dose of humour. The audio performance given at the opening of the exhibition culminates in a cockfight, and at the same time Elín draws the observer to contemplate what happens when a single species takes over – as Eva considers in the case of the lupin. At the exhibition the soundtrack of the performance is played randomly in a “surround” audio system, as a memento of the performance. Elín’s works are omnipresent in the space, reminding us to listen out for the sounds of nature and our surroundings. On an old bench which served during the performance as a perch for the chorus, the scores and folders of the performers are left lying. The exhibit, as for a choir practice or concert, brings the concept of a concert into the exhibition space, and the display as a whole is viewed in a new context. In her art Elín Gunnlaugsdóttir has highlighted the act of writing musical notation artistically. “By writing out Thoreau’s Dream and displaying the score, the visitor to the exhibition can interpret the work and the performance, although it is long past. For what is a score, other than a script, or a map of the territory of sound?” Elín’s visual presentation has a twofold role: in addition to its own innate beauty, it highlights an abstract approach. Reading the score thus demands not only sound literacy, but also interpretation and visual literacy. The observer must thus create their own independent meaning that relates to their prior experience and knowledge.

Thoreau was far ahead of his time in addressing the subject of sound. His book includes an entire chapter devoted to Sounds. He writes about “found” sounds, as Elín Gunnlaugsdóttir does in her audio installation, remarking that all sources of sounds provide the makings of music. As an indication how forward looking Thoreau was, John Cage, the renowned avant garde composer and pioneer of experimental music, came up with similar ideas a century after Thoreau. Elín’s poemaudio work, The Village, in the lobby, is a metaphor for the gossip Thoreau became aware of when he went into the nearby village. It also evokes the news reportage and scandals of today in broadcast and social media, visited by most of us everyday, which composes our “village,” our source of gossip. Elín brought in several friends and relatives as participants in the project, together with birds in her home community, to lend their voices. All the words and sounds coalesce into a babbling mass – as gossip generally does. The work also engages in dialogue with the social reference of Eva’s vase, which provides visitors with an opportunity to consider their own response to their experience of the exhibition.

Walden, or Life in the Woods was first published in 1854. The book’s message has been passed down from generation to generation, each absorbing its lessons in their own way. An Icelandic translation by Hildur Hákonardóttir and Elísabet Gunnarsdóttir was published in 2018. The book addresses major issues, as Thoreau, like the artists behind Thoreau’s World, rethinks his relationship with society and with the environment, and the role of art in culture. The installation at the LÁ Art Museum entails in a sense what Thoreau set out to do: to see, to listen, to persuade people to think about their environment. He absorbed his surroundings with eyes that channelled into his mind ideas that sparked his imagination and a creative approach which is manifested in the form of diverse metaphors and narratives. The three artists’ installation is characterised in the same way by ordered metaphors, each of the women having used the content of the book to enrich her own flow of ideas as they consider daytoday existence and the values that are worth living by. Thoreau detested waste of all kinds, and the exhibition is in his spirit, as the artists unconsciously worked on that principle by using materials sourced from the immediate environment of each.

Curator: Inga Jónsdóttir

Inga studied art at the Iceland College of Art and Crafts and Akademie der Bildenden Künste í München, Germany. She also completed a Diploma in Project Management and Entrepreneurial Education from the Continuing Ed. University of Iceland. Inga founded and curated the Art Festival Á Seyði in Seyðisfjörður in 1995 and 1996. She was also the project manager of the Glacier Exhibition at Höfn, which was opened in 2000 and ran for several years, where art was also a subject matter. She was the first employee of the Svavar Museum at Höfn and was a curator of the international art exhibition Camp Hornafjörður in Höfn in 2002. Inga became the director of LÁ Art Museum in 2007 where she has been the curator of numerous exhibitions.

About the artists:

Auður Hildur Hákonardóttir

Hildur was born in 1938. She graduated as a weaver in 1968 from the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Iceland University of the Arts), then pursued further study at the University of Edinburgh. In 1980 she qualified as a teacher of weaving from the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts, where she taught 1969-1981. She was principal of the college 1975-1978 during a time of turmoil in its history. Hildur has practised her art for many years, and her work has been shown at solo and group exhibitions in Iceland and abroad. She has also developed and presented many exhibitions of the work of other artists. Works by Hildur are in the collections of the National Gallery of Iceland, the Living Art Museum, the LÁ Art Museum and other public bodies. She was an active member of the SÚM artists‘ group in the 1960s and 70s, and in the women‘s liberation movement, and these influences are manifested in her art. Hildur is also well known for her horticulture and her writings. She translated Walden, or Life in the Woods into Icelandic with Elísabet Gunnarsdóttir, and has shown a concern for the environment, as is reflected in her work.

Hildur has undertaken various elective offices, and she was director of the Árnessýsla Heritage and Art Museum 1986-1993, and of the LÁ Art Museum 1997-2000. After residing for many years by the Ölfusá river in south Ice land, Hildur now lives in Reykjavík.

Elín Gunnlaugsdóttir

Elín was born in 1965. She graduated as a music teacher from the Reykjavík College of Music in 1987, and in musicology from the same college in 1993. She completed postgraduate studies in composition from the Royal Conservatoire in the Hague, Netherlands, in 1998. During her student years Elín was an active participant in the Ung Nordisk Musikfest (UNM) festivals. In 1995-1996 she was selected to participate in the composition workshop of the Stavanger Symphony Orchestra, and she has three times been composer in residence at the Skálholt summer concerts, in 1998, 2004 and 2011. Elín‘s works are predominantly chamber works and songs, but in recent years she has been composing music for children, including a musical, Björt í sumarhúsi, a children’s ballet, Englajól, and a theatre work, Nú get ég. Elín works with diverse forms and with other artistic disciplines, for instance in her children’s works, and also in her Póstkort frá París (Postcards from Paris), which was literally written on postcards from Paris, which she sent to the musicians in stages. No less visual than musical, the work has been exhibited, published in book form, and issued on CD. Since graduation Elín has lived in Selfoss, working as a composer and teacher. She is now an adjunct lecturer in composition and musicology at the Iceland University of the Arts.

Eva Bjarnadóttir

Eva was born in 1983. After studying for a year at the textile department of the Reykjavík School of Visual Arts, Eva went to the Netherlands, graduating in 2016 from a four year art programme at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. During her student years she took part in workshops and group shows, including the Urbane Künste Ruhr arts festival in Germany in 2015. Eva‘s contribution was the ten day walk from her home in Amsterdam to the Halfmannshof arts community. On arrival she invited visitors at the festival to have a private conversation with her, during which she talked about her walk and answered questions. The performance work was premised inter alia on the idea that each individual perceives reality in their own way, and hence the narrative and the dialogue are contingent upon the recipient. After graduation Eva returned to Iceland and made her home in Öræfi in the southeast, where she has taken over part of a disused abattoir, which she uses as her studio and also to host arts events. In 2018 she was awarded the Hornafjörður Culture Prize. In the summer of 2019 she opened her first solo exhibition, Í morgun- sárið, at the Midpunkt gallery in Kópavogur. That same summer she held an art event on the Skeiðarársandur glacial sands in the southeast, ÖR-List.