Periods / Turning Points

Pétur Thomsen

May 14 – August 1, 2016

Creatively Man Dwells

Sigrún Alba Sigurðardóttir

Assistant professor in cultural theory at Iceland Academy of the Arts

Who creates the world? Is it the woman standing alone outside in the light summer night holding a shovel? Is it the man standing alone in the black winter night with a camera in one hand and a floodlight in the other? Or has man himself nothing to do with the creation of the world? Does nature create itself?

Nature is that chaotic force that grows unhindered both inside and outside of us. Without it there would be no life, no passion, no flow, and no death. Nature creates life and destroys life. Each day we try to harness this life, both the life that stirs within us and the life that takes place outside of us. We train our body, take medicines to keep unwanted changes under control, we manage our desires and direct our passions into appropriate channels. We dig trenches, plant trees, mark out our path, find our place, turn aside from nature to the world of reasoning, rationality, and economic growth. Thus our lives are shaped by a continuous battle with the nature that exists within us as well as outside of us. We cannot allow it to expand unchecked, but neither can we get a firm hold of it. Nature is unpredictable. It manifests itself in more ways than we could possibly imagine. When nature stops surprising us it stops existing as such. It becomes something else. Part of a quantifiable, determinable, man-made reality. Man’s environment.

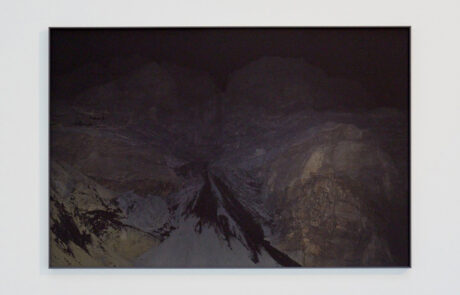

Man stands alone outside in the night, recording the environment he has created and the nature over which he has no control. He illuminates the scene, fixes his eyes on details, and ponders how time has made its mark on the life around him. How nature changes from day to day. Leaves wither, snowflakes fall, the light changes. He breathes in, becomes one with his surroundings, becomes for a short while a part of nature, then takes out his floodlight and his camera — records, transforms, and creates.

As a medium, a photograph deals to a certain extent with time and man’s attempt to preserve the bygone or to draw out particular threads from the flow of time. In our daily lives, we experience reality as a single entity; we look, listen, touch, absorb changes in temperature and smell, we move in space, simultaneously taking into consideration both quantifiable time and our own intrinsic time that controls how quickly or slowly we sense the flow of reality. A photograph can break this flow, but it can also condense it into one specific moment, time’s point of intersection.

Pétur Thomsen’s photographs of living vegetation that grows and transforms during the night deal with nature itself, as well as those details we hardly ever notice in the daily flow of time. They also deal with man’s intervention into this same nature — how man, consciously or subconsciously, affects nature, how he tramples heavy-footed on delicate vegetation, how he plants, digs, takes away and illuminates herbs and plants, so disturbing the rhythm of nature. Technology enables him to see what darkness conceals. The photographer is like an investigator out in the field. He carefully observes his surroundings, looks for traces, brings out details other people might overlook, records, and puts things in order. Internationally, theorists have said that in such a context aesthetics is influenced by forensic methodology; such emphases may be detected both in photojournalism and in fine art photography.¹ With his photographs taken of the environment at Upphæðir in Sólheimar in Grímsnes, of the sand mines on Mt Ingólfsfjall, and of the ditches that drain the moorland in the interests of agriculture in the south of Iceland, Pétur Thomsen writes himself into this tradition. Rather than showing the actual crime or event, he draws your eye to the details and evidential traces in the environment, leaving it to the onlooker to interpret the result. We observe leaves that take on a golden hue under the effects of manmade lighting, and we see how the complicated forms of an ordinary tree branch are highlighted and accentuated against a black surface. A Christmas tree that once adorned a living room gains new significance as it tumbles like a foreign object in a nature it was once part of but no longer belongs to in the same way. The time and light caught by the photographer reveal to us nature’s constant flow, where life and death merge into one entity; nothing lasts forever, but what dies gives life and what comes to an end creates the criteria for something new. A photograph is testimony to man’s attempt to capture this process — to capture the flow of time — before it disappears. The exhibition Periods / Turning Points is a continuation of Pétur Thomsen’s focus on the disruption

of nature that has been prominent in his earlier works, both in his photographs of the Kárahnjúkar power plant project area in his series Aðflutt landslag (Imported Landscape), and in his works Umhverfing (“an Icelandic word for the state between nature and environment”) and Ásfjall (Mt. Ásfjall). These works have been exhibited in venues such as the National Gallery of Iceland, the Reykjavík Museum of Photography, and the National Museum of Iceland. Thomsen’s work has been significantly influenced by the philosophy of Páll Skúlason and his writings about how man continually transforms nature into environment to suit his own needs.² Skúlason defines environment as “the product of man’s creative efforts, taking place when he attempts to change natural scenarios and adapt them to his own needs and wishes.”³ Man sees nature as a creative force over which he longs to gain control, while at the same time realising that it is only because he is able to define himself as a creature standing apart from nature itself that he can define himself as a creative individual. Man is part of nature while simultaneously standing outside it. This is one of the themes of Thomsen’s works in the exhibition Periods / Turning Points, and thus resonates ideas that can be traced back to when photography was invent- ed at the beginning of the 19th century.

The photograph is based on a simple chemical discovery — indeed, in itself it seems strange that it took until the 19th century for this simple discovery to emerge. The French philosopher Michel Foucault has discussed how the zeitgeist of each period links to what he calls the period’s episteme, a concept that may be used to define the possibilities and limits of knowledge at any given moment. In his book Les mots et les choses (The Order of Things) Foucault argues that at the turn of the 19th century the epistemic premises that had emerged made it possible for man to experience himself simultaneously as both a subjective personality and an objective creature that is to some extent not free in thought and, consequently, deed.⁴ In other words, man perceived himself as being part of nature while also feeling able to separate himself from nature. What characterises “modern man” in this sense is the fact that he accepts his limits while trying at the same time to overcome them by deploying scientific methods and, as he does so, he discovers the potential that comes with approaching reality on his own terms and in different ways that were not possible in the past. Modern man realises that truth is not completely under his control, that between him and reality are certain limits but, at the same time, it is his subjective evaluation of this reality that gives him access to truth. Thus truth becomes both absolute and relative at the same time. This breach between the absolute and the relative kindles a longing in man to overcome the unbridgeable gulf between self and reality. He longs to master reality, invent a method that will enable him to create an objective and true picture of the reality that surrounds him.⁵

In his book Burning with Desire, Geoffrey Batchen explains how man‘s longing to take hold of reality in this way gradually changed in the years after 1800 from fantasy-linked pipe-dreams to realistic scientific experiments. Working independently, not comparing techniques, scientists in Britain, France, Brazil and the United States carried out experiments all with the same aim, to find a way to capture reality with the help of the sun and some previously undiscovered chemical compound.⁶ In Britain it was the mathematician, linguist and amateur painter Henry Fox Talbot who was the first to introduce a method he had developed to fix a silhouette picture of nature on to paper that had been soaked in photosensitive liquids. In 1840 he took out a patent on this technique, calling it talbotype. He said he’d had the idea for this invention seven years previously as he stood by Lake Como in Italy trying repeatedly, without success, to draw a believable and true picture of the environment he was looking at. “Suddenly,” he said, “I had this idea […] how wonderful it would be if it were possible to get nature itself to leave a permanent image on the paper?”⁷ In a photograph it is, indeed, nature itself that leaves its mark; behind each photograph there are certain chemical reactions, although it isn’t nature itself that initiates these chemical reactions, but human intervention. In a paper titled Photogenic Drawing or Nature Painted by Herself that he presented to the Royal Society in London in 1839, Talbot discussed man’s interaction with nature, and pointed out that photography is at the same time a method to produce an image creatively and a technique for reproducing reality without any human interference taking place. This statement defines nature as both an active agent and an inactive participant, just as the photograph itself is always an offspring of nature as well as a cultural product.⁸

Henry Fox Talbot saw the photograph as a creative medium that he could utilise to study the world, as well as a tool that enabled him to record the flow of time and whatever presented itself to his point of view. His photographs are a source depicting the reality that confronted him on a grand country estate in Britain at the beginning of the 19th century; they are also a source of his view of the world, his attitude to nature, his inner struggle and urge to preserve reality while at the same time making his mark on it. This is why Talbot’s story is what springs to mind as I look at Pétur Thomsen’s photographs and visualise him creeping around in the darkness of night with his camera, illuminating the world and capturing a fragment of the flow of time in a picture. Thomsen captures nature as it is, but he is also aware that nature always appears to each individual observer in a particular way. How does nature exist if man’s gaze is not directed at it? How does man’s point of view shape the nature that appears before his eyes? In his book Phenomenology the Danish philosopher Dan Zahavi says: “A phenomenon is how a thing appears to us as seen with our eyes, but not how the thing is in itself.” He adds: “If we aim to grasp how the thing is really constructed, we need to focus our attention on how it reveals itself and appears, whether in perceptual experience or in scientific analysis.”⁹ In other words, man’s viewpoint always touches reality and affects how it appears to us, whether in a photograph or in reality, regardless of what methods we use to touch and analyse what is before our eyes. “I play very purposefully with the viewpoint in my art,” Pétur Thomsen says. “My works are all very subjective and are above all a record of how I see things and express myself about what I see. My landscapes reflect this. I have always defined landscape as a perspective that is linked to cultural upbringing and the symbolic system of our culture. In my photographs I create landscapes that I bring to the viewer.”¹⁰

In creating the works on display in the exhibition Periods / Turning Points, Thomsen uses a digital camera. In his photographs there are no natural chemical reactions in action, only man-made formulae that convert light into numerical values and data that are then processed into a reproduction of reality. Thomsen has, nevertheless, much in common with early photographers such as Henry Fox Talbot, and although nearly two hundred years separate their work in time, both seem to possess the talent to dwell creatively and poetically within their environment. Their photographs display clearly how man, who dwells in nature, becomes a part of time’s flow, and how he becomes a part of nature as he transforms it in a creative way. Poetically Man Dwells is the title of a text by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who takes this title from the poet Hölderlin.¹¹ In his poem Hölderlin links man’s stay on Earth, the star- bright sky above, and our inability to measure what matters in the world. The man who creeps out at night to photograph the flow of time is not an unbiased recording agent; he is someone who dwells poetically and creatively in his environment, he transforms it, sensing the interplay between nature and culture in that deep silence where time is not broken up into man-made units but merges with the breath of life.

Curator: Inga Jónsdóttir

Pétur Thomsen

Pétur Thomsen was born in Reykjavík in 1973, and now lives and works in Grímsnes, south Iceland.He studied French, art history and archaeology at the Université Paul Valéry in Montpellier, France in 1997-99. In 2001 he graduated with a BTS degree in photography from the École Supérieure des Métiers Artistiques in Montpellier, and in 2004 he completed his MFA degree from the École Nationale Supérieur de la Photographie (ENSP) in Arles, France. Thomsen is a founding member and former chairman of FÍSL, The Icelandic Contemporary Photography Association, and one of two directors of The Icelandic Photography Festival. He has exhibited extensively in Iceland and abroad, and his works are found in public and private collections in Iceland, France and Switzerland. He has been nominated for prestigious awards, winning for example the international LVMH Young Artists’ Award, and has been a recipient of an Artist Salary from the Icelandic Ministry of Culture.

In 2005 Thomsen was selected by the Musée de l’Elysée in Switzerland to participate in the exhibition ReGeneration, 50 Photographers of Tomorrow, and his solo show Imported Landscape at the National Gallery of Iceland was selected Exhibition of the Year in 2010. His recent work has focused on man’s attempt to dominate nature – man’s transformation of nature into environment.

Here you can download the catalogue in Pdf. format.