Photos (c) Simone De Greef and Kristín Scheving.

Sums & Differences

Gary Hill, Steina & Woody Vasulka

September 17th – December 18th 2022.

The exhibition Sums & Differences at Listasafn Árnesinga—LÁ Art Museum brings together works by Gary Hill, Steina and Woody Vasulka. It aims to present the commonalities of their earliest explorations and the subsequent divergence of their artistic practices, their conceptual, performative, and contemplative interpretations of the physical and the immaterial, along three unique trajectories. This collaborative project offers a new, albeit reductive, path through the artists’ extensive practices. In the exhibition the mutual exploratory relationship between image and sound is highlighted. The spectrum of work spans several decades and presents early exploratory pieces which use electronic processing tools that document real-time machine interactions and their performance and use as an augmentation of the senses. Additional works reflect the development of the artists’ individual vocabularies and illustrate how they utilize, examine, and break with the algorithm or code in a unique way through their experiential research. Steina’s new work Parallel Trajectories and Gary Hill’s new piece None of the Above will be premiered at the exhibition and the rarely seen film works Peril in Orbit and 360 degree space records by Woody Vašulka will be featured in this new unexpected constellation.

Curated by Jennifer Helia DeFelice, Halldór Björn Runólfsson and Kristín Scheving.

—————————————————————————————————–

One Plus One Equals Three: “Sums & Differences: Gary Hill, Steina & Woody Vasulka”

“Matisse/Picasso,” “Manet/Degas,” “Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian”…Two person exhibitions seem to be a favorite of art institutions. Take two famous artists, pit them one against another as in a kind of contest and you are garanteed to have a block buster. Sometimes the formula also succeeds artistically, and sometimes it just doesn’t. One would expect it to be even harder to do when you are dealing not only with two, but three artists as was the case with “Sums & Differences,” which brought together the work of Gary Hill, Steina, and Woody Vasulka. The fact however is that this survey of three of the most important pioneers of video and digital art stood out as a particularly intelligent and elegant curatorial model for managing the duo (or trio) exhibition format. Rather than a classic retrospective, the exhibition provided entry points into key aspects of each oeuvre through a carefully selected choice of pieces (comprising films, single-channel videos, installations, and photographs). Three monitors with a video on demand program were installed in the foyer of both venues (the show opened at Listasafn Árnesinga—LÁ Art Museum and then traveled to House of Arts Brno, in the Czech Republic), enabling the viewers to complete their visit by accessing, separately from the main exhibition, a selection of the most representative single-channel videos produced by each artist. Avoiding simplistic and pseudomorphic comparisons, the exhibition let the works freely resonate one with another, allowing them ample space to “breathe” and unfold their meditative and immersive beauty.

Of course, it helped that the artists featured in the show fit together very naturally. To begin with, Steina and Woody Vasulka were actual partners, both in life and work. Steina the Icelander and Woody the Czech met in the early 1960s in Prague where she was studying to be a concert violinist and he was training as a filmmaker at the Film Academy. Married in 1964, the two soon after emigrated to the United States where, at the end of the decade, they discovered video. They were both immediately captivated by the possibility it offered them of working directly with electromagnetic energy. From then on, they dedicated themselves to a systematic investigation of the properties inherent to their novel material, at first in tandem, and then separately, but always in dialogue with one another. As for Gary Hill, although younger than the Vasulkas, he began experimenting with video roughly at the same time as they did and moved in the same circles of early US-American video and electronic music experimenters. More importantly, when all three finally met in the late 1970s they felt an immediate kinship. Indeed, they shared the same fundamental idea that the electronic image was a new specific idiom with its own idiosyncratic code and that it was the tool or the machine, rather than the “artist,” that was paramount in the creative process. This is no to describe their practice as a belated rehearsal of the Modernist discourse of medium-specificity, which at the time was clearly on the wane. Quite the contrary, as demonstrated by the exhibition, which covered the period from the 1970s up to today, the works of both the Vasulkas and Hill deserve to be recognized as essential milestones in the genealogy of our digital age in which machine literacy is more than ever a crucial issue.

At the same time, and as the title of the exhibition made clear, the approaches of all three artists are different enough that it does not make any sense to speak of their art in terms of either influence or rivalry. “Sums & Differences”: the phrase refers to the signal processing function of ring modulation in electronics. Ring modulators serve to mix two frequencies, outputting their sums and differences. Both the Vasulkas and Hill were in effect experts at signal processing, a method they were introduced to at first by their common interest in electronic music. On a more abstract level, the title of the exhibition points to the idea of dissymmetry that recurred in various ways throughout many of the pieces on view. This concept designates situations in which symmetry is not exactly lacking, but where there is nonetheless a slight discrepancy or a handedness between two patterns or entities. In a nutshell, it is what we mean when we say that two things are the same, but different.

Such, in a way, is the relation between image and language, a conception well illustrated by Gary Hill’s installation Language Pit (2016-2021). In this piece, micro-cameras are laid upon the skin of two speaker cones installed on a plinth. The cameras record a live-feed of the space, which is projected onto two monitors hung adjacently on the wall opposite the speakers. The vibrations of the sound coming through the speakers cause the cameras to ricochet on their surface, so that the flow of images is constantly disrupted. The manner in which the speakers and the monitors are installed evokes two pairs of eyes, but whereas in everyday experience we forget the binocular reality of vision, in this particular case the dissymmetry is emphasized at the same time that the work destabilizes the distinction between sound and image.

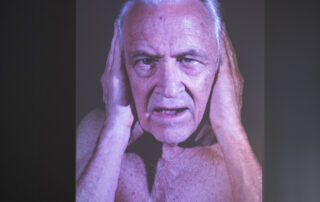

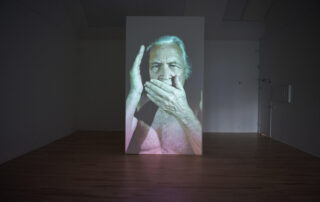

The piece, however, is not all metaphysics. The text delivered by the speakers in an aggressive automated-sounding voice was inspired by Hill’s visceral reaction to Donald Trump’s election. The artist thus addresses the ever-growing brutality of politics and the expanding rule of surveillance in our societies of control, whose advent Gilles Deleuze foresaw in the early 1990s, but which have only truly become a reality with the recent naturalization of digital technology. A decisive factor of this evolution is the development of predictive algorithms, whose power Hill nonetheless challenges in the script of his installation: “Algorithms predict outcomes. How come?” Probabilities are also the main theme of Place Holder (2019), a video in which the artist, facing the viewer, is seen repeatedly tossing a coin in an obsessive game of heads or tails. The work references AI, but in such a way as to put it on a level with good old magic tricks. Mimicking the binary logic of Boolean algebra, the either/or rhythm of the coin flipping movement is picked up again in the choppy editing of None of the Above (2022), a video that Hill premiered at the exhibition. Here, the viewer is confronted with a large-scale video portrait of the artist reciting a text that explores the “same difference” between zero and one. Time displacement digital effects make the image and sound, so to speak, stutter. Alternately covering his eyes, ears and lips with his hands, in gestures alluding to the idiomatic expressions “see no evil,” “hear no evil”, and “say no evil,” Hill also suggests how the digital has reinforced humankind’s solipsistic tendencies.

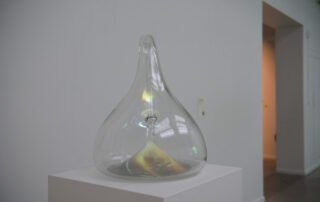

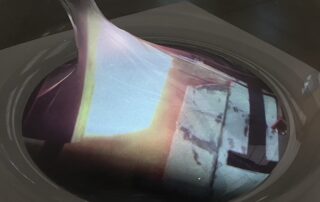

The topological circularity of inner and outer similarly informs Hill’s earlier Klein Bottle with the Image of Its Own Making (after Robert Morris) (2014), a glass geometrical object akin to a Möbius strip, which “contains” the projection of the video of its own making. Paying homage to the Minimalist Robert Morris’s sculpture, Box with the Sound of Its Own Making (1961), the piece, with its twisted shape, reminiscent of an alchemist’s retort, simultaneously highlights the plasticity of the electronic image. In a different but related way, Steina and Woody Vasulka insisted on the materiality and even the “thingness” of the electronic image. In Steina’s Bad (1979), an experiment with an early digital video processing tool conceived by the Vasulkas themselves with the assistance of the engineer Jeffrey Schier, the image is made to disclose its fabric-like texture. The tape’s mysterious title possibly refers to the way that Steina deliberately disrupted the normal functioning of the program, thus producing a masterpiece of glitch avant la lettre. “Bad” also echoes Hill’s “evil,” suggesting something intrinsically demoniac about electronic media. This idea permeates as well Woody Vasulka’s ghostly Electromagnetic Objects (1975), abstract videos that feature white three-dimensional shapes spun with the strangely ethereal matter of the electronic image, floating on a black background. Videographic companions to musique concrète’s sonic objects, these works, although made with an analog tool (the Rutt/Etra Scan Processor), are directly related at the same time to the emergence of computer graphics’s “image objects .”

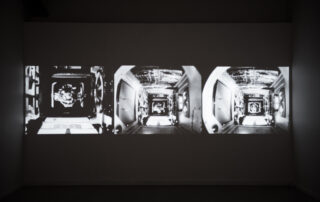

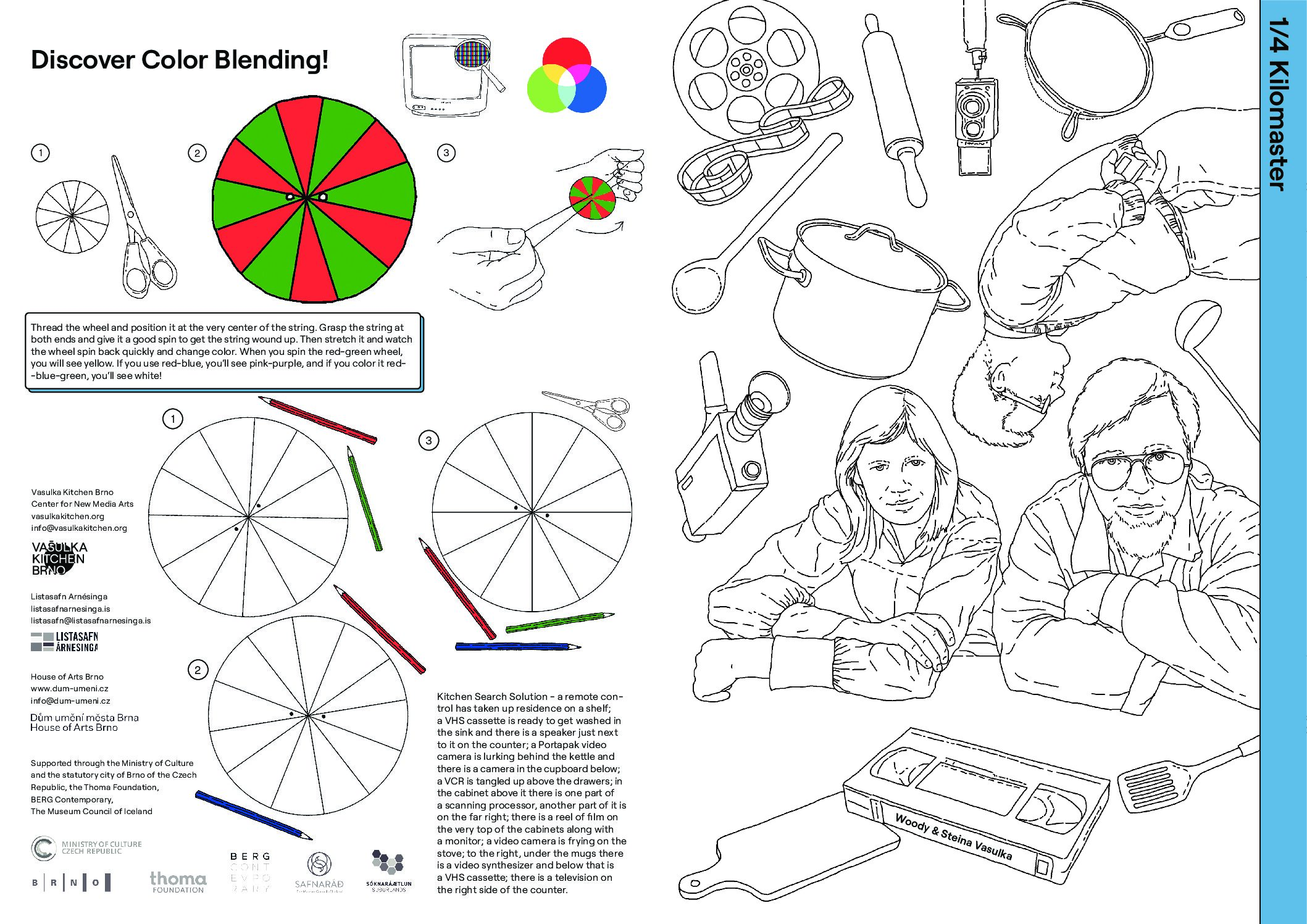

Of the three artists in “Sums & Differences,” Woody Vasulka, who sadly passed away in December 2019, is probably—and unfairly—the least well known. With Parallel Trajectories (2022), a video that also premiered at the exhibition, Steina, in a moving tribute to her former partner, sets out to correct this. Intertwining excerpts from both his work and hers, the artist demonstrates in her own way the non-Euclidean truth that parallels do meet. Another highlight of the exhibition was the presentation of two of Woody Vasulka’s rarely seen early film works. Shot in 1968, in the period immediately preceding his first discovery of video, Peril in Orbit and 360 Degree Space Records are three-screen installations that originated in Vasulka’s obsession with freeing the image from the confines of the frame. Peril in Orbit is particularly interesting in that it shows the kind of camera device that the artist, initially trained in engineering, built to achieve a continuous 360 degree image. Some of these machines were later refitted to construct Steina’s important Machine Vision installations (1975-). Anticipating current discussions of computer vision and of the decentering of the human eye, these environments were present in the exhibition thanks to the fascinating videos Switch! Monitor! Drift! and Orbital Obsessions (1975-1977) that the artist created with them.

As it is, one of the key lessons of the exhibition is that the newness of so-called new media is as old as the medieval parchment manuscripts recording Icelandic sagas whose images Steina manipulates digitally in the video Pergament (2014). For the Icelander, who left her native country over half a century ago, this work has something of a homecoming. But, like the other pieces in “Sums & Differences,” there is nothing nostalgic about it: it only manifests how art and technology always topologically twist back on the past to better move forward into the future. (1701 words)

Larisa Dryansky

Art Historian at Paris Sorbonne University.

1. See Jacob Gaboury, Image Objects: An Archaeology of Computer Graphics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2021).

Download pdf here:

.

Supported by: