Modern Women

March 8 – May 11, 2014

Hrafnhildur Schram

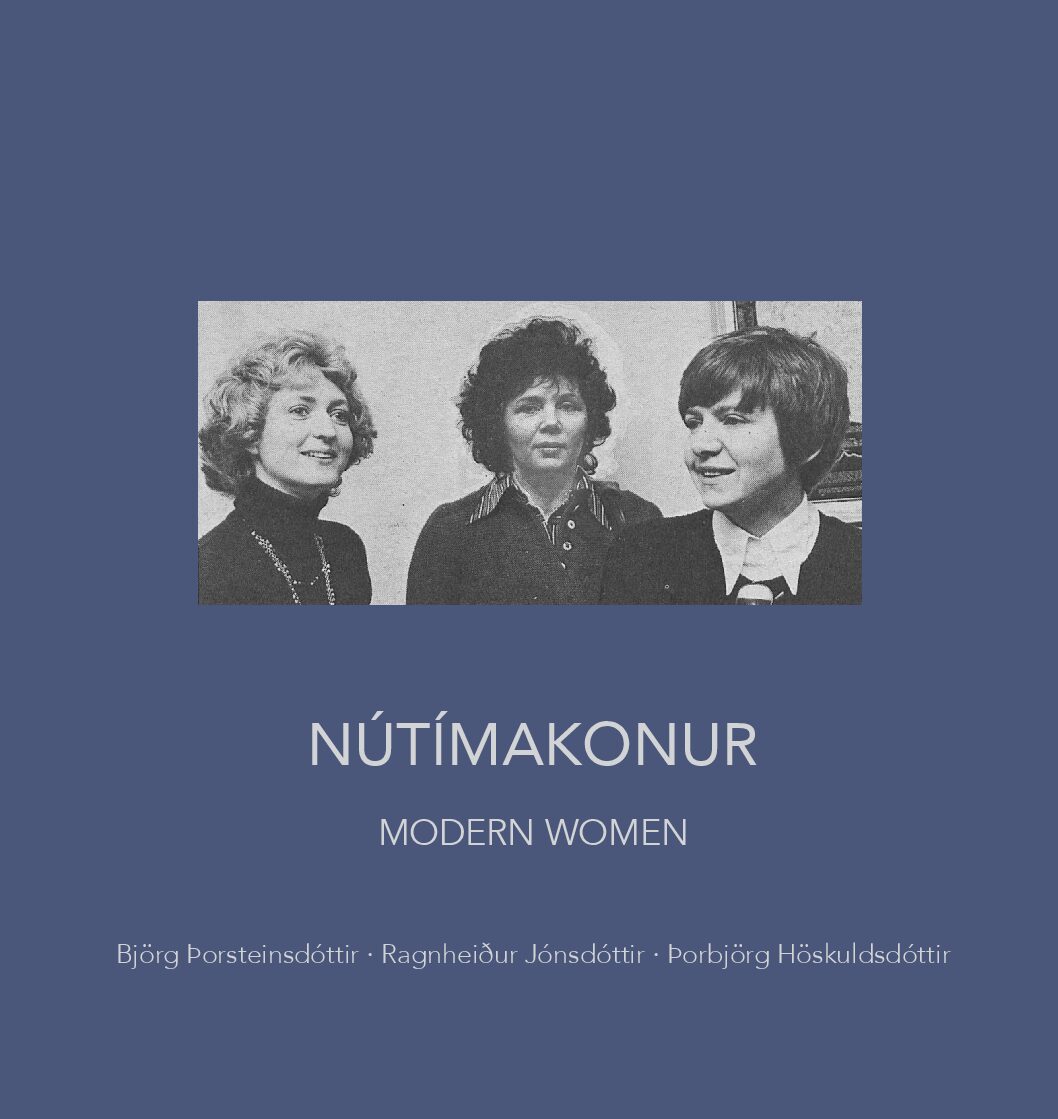

The collection of the LÁ Art Museum includes three works by the artists Björg Þorsteinsdóttir, Ragnheiður Jónsdóttir and Þorbjörg Höskuldsdóttir. They date from the 1970s – that remarkable decade often referred to as the “women‘s decade,“ when the modern women’s movement, sometimes called the second wave of femi- nism, blossomed spectacularly on both sides of the Atlantic. This exhibition, Nútímakonur/Modern Women, provides an opportunity to explore the visual world of these three women, in past and present. Their paths first crossed when as young and aspiring artists they attended courses at the Reykjavík School of Visual Arts. Each has enjoyed a long and fruitful career in art, and none of them has compromised, nor considered a dignified “retirement.” The title of the show, Modern Women, is an allusion to the formative years of the three artists having been the postwar period, when Icelandic society had undergone a transformation from an age-old Nordic agrarian society into a modern urban nation. During World War II Iceland was largely cut off from the outside world, but after the end of the war a whole new world opened up to young Icelanders. They travelled abroad for study and work and, perhaps not least, they went in search of self-realisation. The postwar years were thus a time of ferment: international trends in literature, visual art and fashion rapidly reached Ice- land, and made their mark on Icelandic life and culture. Part of that climate was that women gained ever greater freedom: politically, educationally, economically and sexually. The young generation of that time is undoubtedly the generation of Icelanders who had more choice than any before them about their own futures – their education, and their chances of pursuing their dreams. But professional ambition was long regarded as an un- ladylike attribute; and well into the twentieth century the environment was not receptive to woman artists, who were simply not taken seriously. The opinion was widely held that artistic genius was a “golden nugget” that was bestowed on certain males, and required only to be set free.¹ Traditionally, masterpieces were created by men, while woman’s sphere was to beautify the home; and that tended to become the role of women artists who married their male colleagues. Women artists who were able to work independently, and did not marry, often found it hard to gain acceptance.

They rarely received public grants on equal terms with men, and they were not eligible to join artists’ organisations which provided a platform for promotion of their work. In recent years the pioneering women artists have attracted attention; in their own time they received neither the attention, nor the respect, which they deserved, but they have now been brought out into the light again after extensive research work. Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862- 1944) is an example: research in recent decades revealed that she was painting abstract works as early as 1907, four or five years before Wassily Kandinsky, one of the recognised pioneers of abstract art;² and French-American sculptor Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010), had to wait until the end of her career, when she was in her seventies, to gain the recognition that had previously been accorded only to men.

THE INFLUENCE OF NATURE

Human beings have always seen themselves in the context of nature, and man and nature are bound together by unbreakable bonds. Nature is all around, and that is reflected not least in visual art – whether the artist’s approach is abstract, conceptual, or anything else. Art history is an important source of knowledge of this relationship; yet it was not until the late fifteenth century in Venice, Italy, that nature found its way into paintings. Initially nature served as a background or backdrop, portrayed in a fragmentary manner, pars pro toto (the part for the whole). The Venetian school of artists were renowned for their lyrical portrayals of man’s relation- ship with nature; their colours were deep and saturated, and they used the new technique of oil painting.

It is a familiar trope that Icelanders never noticed the beauty of their own country until it was presented to them in the paintings of the pioneers of Icelandic landscape art in the early years of the 20th century. The three artists whose work is on display here have all worked under the influence of nature – though each in her own way. Another quality they share is a critical and observant eye for society, often relating to nature conservation, which was important to many young artists and had a major place in art in the 1970s.

Björg Þorsteinsdóttir commenced her art studies in 1960 in Iceland, then went to the State Academy of Art in Stuttgart, Germany, where she focussed on painting. But after a course in etching taught by Einar Hákonarson in 1968-9 at the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Icelandic Academy of the Arts), she turned her attention to printmaking. In 1971 she held her first one-woman show at Unuhús in Reykjavík, exhibiting etchings and aquatints. Graphic art rapidly gained popularity in Iceland; it was an ideal medium for disseminating the ideology of the time, and in addition it was democratic in nature, as it enabled people to buy art at an affordable price.

Alongside her painting, Björg continued to work on printmaking for longer or shorter periods, depending upon her circumstances at the time, commissions, ex- hibitions, etc. She explored the qualities of the medium, and attracted attention for her disciplined approach and her fertile imagination. In 1970 Björg went to Paris to study with British printmaker S. W. Hayter in his studio, Atelier 17, founded in 1927. Hayter’s atelier has been described as a sort of experimental laboratory for engraving. Hayter developed a new technique of simultaneous printing, using different inks on a single plate, instead of separate plates for each colour. Björg made her last large prints around 1987, after which she concentrated her energies on painting, as did many of her colleagues in the Icelandic Printmakers’ Association at that time. Björg has found subjects in her own immediate environment and common- place objects, including women’s garments –dresses, gloves and swimsuits – to signify the female, first in her prints, and later in her paintings. No doubt many people recall her paintings of colourful dresses fluttering in an indeterminate space – but she could adapt the soft shapes of the garments as she wished: sometimes they were inserted into strict geometrical frameworks, which counterbalanced the free, rounded forms. Björg now works on her paintings, which may be classified as lyrical abstract, in both acrylic and watercolour. Over the years she has moved away from visible reality, and her colour palette has grown stronger and brighter. Here in this exhibition Björg is showing works in which nature itself has provided her with a subject, e.g. water and the variations of its hues and surroundings. Her fluid brushwork conjures up enigmatic expression on the picture plane, and the artist follows where her hand leads, onward to her conclusion, expressing her impressions and achieving equilibrium in composition and colour. Björg is an amateur photographer, and takes pictures of water, the sea and reflections, but she does not use her photographs as a model for her paintings, as she feels that the photograph should exist on its own terms.

Ragnheiður Jónsdóttir studied drawing in Reykjavík and then in Copenhagen. She formally launched her artistic career with a one-woman show in Casa Nova at Reykjavík High School in 1968. But after a course in graphic art at the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts, taught by Einar Hákonarson, she switched over to printmaking, and in 1970 she participated in the first exhibition of the newly-revived Icelandic Printmakers’ Association. That same year she went to Paris with Björg Þorsteinsdóttir, and they spent the summer working on their graphic art at Atelier 17 with the renowned S.W. Hayter. One of the most influential printmakers of the twentieth century, Hayter strove to promote printmaking around the world, working with all the leading artists of his day, including Wassily Kandinsky, Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró.

By the mid-1970s public opinion had changed and there was greater appreciation of modern art. A major difference was that women in the creative arts had become more visible. Social realism emerged, referencing the reality of those turbulent times; women started to interpret themselves and their position on their own terms, and create art that reflected their own lives. The “feminine experience,” arising from women’s shared experiences, became valid and visible as a theme in art, of as much value as any other theme; and at the same time it entailed a shared human significance. In 1975, the UN’s International Women’s Year, on 24 October the women of Iceland took a historic Day Off and held mass meetings in order to underline the vital contribution they made in society. The Women’s Day Off inspired Ragnheiður to make prints which to many minds sum up the solidarity and unity of that day. Her one-woman show at the Nordic House in Reykjavík the following year demonstrated that she had something to say to the people of Iceland. In symbolic form, in more than forty etchings, she expressed ideas that many others would have liked to articulate. Courageously and with insight she targeted various social ills not least the lack of care and respect for nature. The start of the 1990s heralded a new period in Ragnheiður’s art: she has spoken of the sense of liberation she experienced when she largely abandoned printmaking and turned to drawing with charcoal on paper. In her series of abstract charcoal drawings Storð and Slóð/Trail, the content of which is a logical continuation of her printmaking, her theme is once again man’s relationship with nature. That vision is now presented in more uncompromising terms: the last drawings in the series Storð depict scorched earth, withered grass, convocation of wriggling worms, and finally a dead landscape.

Þorbjörg Höskuldsdóttir chose her visual world early in her career – Icelandic nature. And she has remained true to it, interpreting it unceasingly for the past four decades. It is clear that she has strong feelings about her country, which she succeeds in expressing in a highly personal and sincere manner. The universe may appear to be infinite, but the same cannot be said of natural resources. Fire, water and wind are no longer alone in shaping the land: man too transforms nature according to his whimsies and caprices. The impact is, as a rule, irreversible; and man’s relationship with nature is one of Þorbjörg’s overriding themes. In her first one- woman show at Gallery SUM in Reykjavík in 1972 she first presented the mountain world with which she has kept faith and renewed over the years. During her student years at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts she focussed especially on perspective drawing, and was for a time the only student at the academy in that field.

Þorbjörg has made use of this expertise, as in many of her works perspective drawing constitutes a matrix, or counterbalances organic natural forms. Motifs from classical times are often seen, such as Roman arches, columns, tiled floors or other architectural features which evoke unexpected resonances, arising from the juxtaposition of the ancient world with a young culture and a familiar landscape. Without saying too much or proselytizing, the artist often evokes a bleak vision of the future in which the observer senses an underlying menace – while a subtle ironic undertone is ever-present.

Þorbjörg often seeks out barren mountains with strong contours, in the uninhabited interior of Iceland or on the Reykjanes headland in the south- west. She painstakingly selects a point of view and considers forms, colours and textures, then opens her sketchbook to put on paper the potent impressions aroused by both weather and winds. But above all she takes a lot of photographs, in order to capture the shifting light or a veil of mist drifting by.

The best time of year is the autumn when the air is pellucid and the low sun casts elongated shadows; she doesn’t like to paint in bright sunshine, when she finds the colours more muted. Her colour palette is composed of earthy tones and hues of blue, while green is strikingly absent. We recognise the mountains as soon as we see them in Þorbjörg’s paintings – but sometimes it is the title which puts us on the right track. After that moment of recognition, however, they become some- thing entirely different in our minds, as we see them through the artist’s eyes as unique, mystical, super- natural phenomena.

¹Linda nochlin: Why Have There Been no Great Women Artists? ( Sic) Art news, 1971

²Abstraktið, hið óhlutbundna málverk, varð til nánast samtímis á mismunandi stöðum skömmu fyrir fyrra stríð: hjá Wassily Kandinsky í München, Piet Mondrian í París og Kasimir Malevitsj í Moskvu.

Artists

Björg Þorsteinsdóttir

Björg was born in Reykjavík in 1940. She graduated from Reykjavík High School in 1960, and in 1964 she qualified as a teacher of drawing from the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Iceland Academy of the Arts). She also studied graphic art at the College, attended lessons in drawing and painting at the Reykjavík School of Visual Arts, and studied for a time at Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Stuttgart. In 1971-3 Björg received a French government scholarship, and studied engraving with S.W. Hayter at Atelier 17, and lithography at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts í París.

At the start of her career Björg mainly worked in oils, but at her first one-woman show in 1971 she exhibited only etchings. For some years she worked mainly on printmaking, but recently she has focussed on painting. During her career she has painted, drawn and made prints and collages. She has held over 30 one-woman shows, and participated in a large number of international exhibitions in most countries in Europe, as well as in Asia, Africa, the USA and Australia. Examples of her work are in many public and private collections in Ice- land and abroad, including the National Gallery of Ice- land, the Reykjavík Art Museum, the Bibliothèque Nationale in París, Museet for Internasjonal Samtidsgrafikk in Fredriksstad, Norway, the Museo Nacional de Grabado Contemperaneo in Madrid, Spain, and others. Björg has received prestigious awards, and has been granted bursaries from the government Artists’ Bursary Fund.

Björg has been an associate tutor at the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts and the Reykjavík School of Visual Arts, and was director of the Ásgrímur Jónsson Museum 1980-84. She has been active in artists‘ organisations, and served on the board of the Sigurjón Ólafsson Museum.

Ragnheiður Jónsdóttir

Ragnheiður was born in 1933. She was drawn to art from a young age; and her artistic career is also bound up with her role as the mother of five sons, born 1954-68. Ragnheiður graduated with her high-school diploma from the Commercial College of Iceland in 1954. She attended courses at the Reykjavík School of Visual Arts 1959-61 and 1964-8. Her teachers included Erró and Ragnar Kjartansson, and the latter went on to offer her work at the Glit pottery. In 1962 she attended drawing classes at the Glyptotek in Copenhagen. She then entered the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts (forerunner of the Iceland Academy of the Arts), where she studied graphic art with Einar Hákonarson 1968-70. Ragnheiður was in Paris in 1970, studying printmaking at S.W. Hayter‘s Atelier 17.

In 1966 one of Ragnheiður‘s works was selected for the autumn show of FÍM, the Society of Icelandic Artists. In 1968 she held her first one-woman show of paintings, after which she devoted her energies entirely to etching, and established a studio with her own press. Around 1990 she embarked on new challenges when she started making large charcoal drawings. She has exhibited her work at dozens of one-woman and group shows around the world and in Iceland. Examples of her work are in many public and private collections in Iceland and abroad, including the National Gallery of Iceland, the Reykjavík Art Museum, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and the Museum of Modern Art in Helsinki. She has received international awards, and has been granted bursaries from the government Artists‘ Bursary Fund.

Ragnheiður took part in the re-establishment of the Icelandic Printmakers‘ Association in 1969, of which she was a board member. She was also on the board of FÍM for a time. She was one of a group of artists who ran Gallery Grjót 1983-9.

Þorbjörg Höskuldsdóttir

Þorbjörg was born in 1939. She studied at the Reykjavík School of Visual Arts 1962-6, when she was also working as a ceramics designer at the Glit pottery under the supervision of Ragnar Kjartansson and Hringur Jóhannesson. In 1967 she went to Copenhagen to study at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts under the tutelage of Professor Hjort Nielsen. After graduation in 1971 Þorbjörg returned to Iceland, and she has had a long and successful career in art. She has worked mostly in oils, but has also designed stage sets, made graphic art and drawn illustrations for books. The Icelandic landscape has been a constant theme; by juxtaposing it with perspective drawings of classical architecture she draws attention to the delicate relationship between man and nature.

Þorbjörg held her first one-woman show at Gallery Súm in 1972, since then she has held many one-woman shows and participated in group exhibitions, mainly in Iceland but also in Denmark. Examples of her work are in all Iceland’s major art collections. She was one of the artists who ran Gallery Grjót on Skólavörðustígur in Reykjavík, 1983-9. She has been active in artists‘ organisations, and was on the board of FÍM, the Society of Icelandic Artists. Þorbjörg has received bursaries from the government Artists’ Bursary Fund, and since 2006 she has been a recipient of an honorary bursary awarded by parliament.

Curator:

Hrafnhildur Schram graduated from Lund University in Sweden with a licentiate degree. She has been curator of the Ásgrímur Jónsson Collection and the Einar Jónsson Museum and a head of department at the National Gallery of Iceland. Hrafnhildur has taught art history, been an art critic, written extensively on Icelandic art in newspapers and periodicals, and made TV documentaries on Icelandic artists. She has done research on Icelandic women artists, and is the author of the first monograph on an Icelandic woman artist, Nína Tryggvadóttir. In 2005 she published Huldukonur í íslenskri myndlist (Hidden Women of Icelandic Art) about the first Icelandic women who went to Copenhagen for art training. Hrafnhildur is now a freelance scholar, writer and curator. In 2008 she curated a show about the painter Höskuldur Björnsson at Listasafn Árnesinga (LÁ Art Museum).

Here you can download the catalogue in Pdf. format.